![]()

1 Adolescence as life phase and adolescents as group

Adolescence, in Latin adolescentia, comes from the verb adolescere, which means growing up. Growing up entails that adolescents have to master various developmental tasks: starting and completing education, making the transition to an occupational career, setting up their own household, finding and defining their identity, transforming child-like relationships with parents and friends into adult-like relationships, establishing relationships with an intimate partner, and becoming an informed citizen contributing to the solution of societal and political issues. The age period in which adolescents have to master these developmental tasks is between 10 and 25, depending on the society in which they are living. In general, adolescence lasts longer in societies that are more prosperous. This introductory chapter serves to introduce two perspectives on adolescence: that adolescence is a period of turmoil, and that adolescence is the formative period in life. I open the chapter by showing that the emergence of a long adolescence is a relatively new historical phenomenon.

Adolescence: an extended life phase

The emergence of adolescence for all

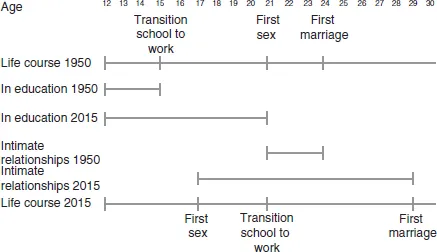

Traditionally, adolescence has been defined as the period that starts with puberty and the entrance into secondary education, and ends with the transition from school to work. In modern Western societies, adolescence has become a life phase for virtually all young people. This emergence of adolescence for all is a relatively recent phenomenon, as can be easily demonstrated by differences in timing of the various important status transitions between 1950 and 2015, see Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The emergence of adolescence for all: status transitions in 1950 and 2015.

The Figure shows the timing of three key status transitions in 1950 and in 2015: transition from school to work, first sex and first marriage. For the Figure, I used aggregated data from the US (Finer, 2007; US Census Bureau, 2010), EU (Eurostat, 2015) and the Netherlands (CBS, 1975; De Graaf, Kruijer, Van Acker, & Meijer, 2012). The transition from school to work marks the age at which young people become available for the labor market. The Figure shows that mean age of moving from school to the labor market was 15 in 1950, whereas it was around 21 in 2015. This implies an expansion of six years in the schooling period for young people. Consequently, the period of the formation of intimate relationships also has become substantially longer. I use two status transitions to describe the formation of intimate relationships. I take the age of first sex as the start of the formation of intimate relationships, and first marriage as the (at least temporary) end of the formation of intimate relationships. In the 1950s, this period was relatively short: around three years. In 2015, the formation of intimate relationships started considerably earlier, at age 17, and lasted longer, until age 29. Taken together, these findings indicate an enormous expansion of the period of the formation of intimate relationships: from three years to 12 years.

A limitation to these figures is that they come from a limited number of Western countries. Therefore, the exact figures should be considered with caution. The core meaning of the figures, however, does not lie in their exactness, but in the trends they indicate. These trends show that the emergence of adolescence is due simply to an enormous extension of the educational period and the period of the formation of intimate relationships. In turn, this is due to the growing wealth of countries. Growing wealth leads to more resources for the schooling of the younger generation, and subsequently to a longer period of exploring intimate relationships and making final choices at a relatively high age. Both trends also show that the emergence of adolescence for all is a relatively recent historical phenomenon.

Sub stages of adolescence

Since it has become a much extended period in life, adolescence can now be divided in various sub stages: early adolescence (ages 12–14), middle adolescence (ages 15–17), late adolescence (ages 18–20), and post adolescence (ages 21–23). This also implies that it is incorrect to mix up adolescence and puberty. Puberty is simply a sub stage of adolescence: early adolescence.

In each of these sub stages some developmental processes and the completion of some developmental tasks are salient (see Table 1.1). Early adolescence is the period of physical development and the transition from primary to secondary education. Middle adolescence is the period of starting to go out, first intimate partner and first sex, and of the transition from secondary to tertiary education for adolescents of lower socioeconomic status. In late adolescence, young people of higher socioeconomic status leave the parental home to make the transition from secondary to tertiary education, whereas young people of lower socio-economic status make the transition from school to work. In post adolescence, young people of lower socioeconomic status leave the parental home, and young people of higher socioeconomic status make the transition from school to work. Taken together, the developments in the various domains nicely illustrate how adolescent development unfolds, and, additionally, show socioeconomic differences. Adolescents with low socioeconomic status move earlier to tertiary education and from tertiary education to work than adolescents with higher economic status, and leave the parental home later. So, with the exception of leaving the parental home, adolescents with low economic status develop faster. This pattern has also been found for first intimate partner and first sex (Hovell et al., 1994). Note that the sub stages of the Table come from research in Western countries; therefore, the exact figures of the timing of the sub stages should be considered with caution.

Table 1.1 Sub stages of adolescence

| Developmental domains | Early adolescence (ages 12–14) | Middle adolescence (ages 15–17) | Late adolescence (ages 18–20) | Post adolescence (ages 21–23) |

| Physical development | – Puberty | | | |

| Personal relationships | | – Going out – First intimate partner – First sex | – Leaving parental home2 | – Leaving parental home1 |

| School and work | – From primary to secondary education | – From secondary to tertiary education1 | – From secondary to tertiary education2 – From school to work1 | – From school to work2 |

Perspectives on adolescence

Turmoil everywhere: adolescence in social sciences and the public eye

Stanley Hall (1904) was among the first psychologists to describe adolescence as a period of storm and stress. He borrowed the term from the eighteenth-century literature movement called ‘Sturm und Drang’ and used it to describe adolescence as a period in which a loss of self-control (storm) goes together with an increasing sensitivity to stimuli from the environment (stress). Although not necessarily correct (Meeus, 1992, and see, for a recent commentary, Hollenstein & Lougheed, 2013), the notion of Hall has become very influential in the description of adolescence in social sciences and the mass media. I offer a couple of examples to illustrate my point.

Absolute beginners: the young always welcome the new

This notion was introduced by the German sociologist Karl Mannheim (1928) who wrote that, more than any other group, young people were willing to embrace and adopt new trends in society. In the Netherlands, the sociologist and historian Prakke (1959) adopted this notion and coined it as the ‘seismographic function of youth’: when societal arrangements or common behaviors or attitudes change, young people will be the first to note and to embrace the new. And indeed, young people were the first to advocate a new sexual morality in the 1960s, to adopt new styles of pop music, for instance rock and roll in the 1950s, beat in the 1960s, punk in the 1970s, and dance in the 1990s, to adopt social media such as Facebook and Twitter in the 2010s, and to support radical political movements, for instance the Red Army Faction in Germany in the 1970s, and more recently IS and the Occupy movement. All these events revolted society, and adolescents were and are very visible as a group that carried the changes.

‘Don’t trust anyone over 25’: generation gap

The prolongation of the adolescent years created adolescence as a separate life phase for the vast majority of young people. So, the invention of adolescence for all, created a socially and demographically very visible social category: youth. Of course, youth has always been a visible category in modern history, but only recently did it become a category of huge proportions. Social identity theory (Tajfel, 1978) and research into social categorization (Rabbie & Horwitz, 1969) explain what happens when a new social category arises. The new category creates its own identity: a group consciousness, a differentiated set of norms and attitudes, patterns of social behavior, and preferences for clothing, music, consumption and spending leisure time. In other words, a youth cultural identity. The creation of the new social category leads subsequently to comparison with other social groups and to identification with its own group. Social comparison between groups entails two steps: the discovery of intergroup differences and the evaluation of them. Typically, groups tend to rate the characteristics of the in-group to be superior to those of the out-group. In the case of youth, adults serve as the preferred out-group, and for most adolescents youth is distinct from, and superior to, adults, which leads to the well-known generation gap. The generation gap has expressed itself in an enormous variety of youth cultures that criticized present-day society and the way it has been built by adults. Although most young people leave the idea of the generation gap behind when they are between the ages of 20 and 30, a minority of them belongs to more radical youth subcultures and is convinced that life after adolescence is no longer worth living. These young people refuse to become adult and to adopt conventional adult roles. However, for the majority of young people ‘live fast, die young’ is not an absolute rule, but more a sentiment that expresses the eternal longing to be young. They often embrace adolescence as the best time of their lives.

No future …

This behavioral pattern reflects the grim variation of ‘live fast, die young’ and refers to an emotion that is latently present in all youth generations: there is no decent place for us in society. A benign and recent example of this sentiment can be observed in recent discussions in European countries where young people complain that pensions for the elderly are too high, which will deprive them of a decent pension when they retire. Another example is that of young Brits criticizing the adult vote for Brexit in 2016, thereby jeopardizing the future of the younger generation. A harsher example could be observed in the suburbs of Paris in 2007–2008. In long-lasting riots, young people of these disadvantaged districts expressed their feelings of no future in severe violence. Recent sociological research (Heinsohn, 2003; Weber, 2013) suggests that ‘no future’ feelings and violence become more prevalent when the relative size of the male youth generation is big (over 20% of the general population), youth unemployment is huge and expectations for the future are high. This theory of the ‘youth bulge’ predicts chances of youth violence in the near future to be highest in African countries south of the Sahara, South Asia, and the Middle East.

The ‘no future’ sentiment is more than a fiction. The notion of generational inequality makes it clear that chances of young people to get their fair share of societal affluence are limited. This can be amply demonstrated when we look at unemployment figures: in times of economic crisis, youth unemployment always rises more sharply than unemployment in the general population. At this moment, the second decade of the twenty-first century, we observe this very high level of youth unemployment in, for instance, Greece, Italy and Spain.

Identity crisis

This concept was introduced by Erikson (1968) in his epigenetic chart of lifelong development. Erikson considered moving from identity diffusion to identity achievement to be the key developmental task of adolescence. According to Erikson, the experience of an identity crisis is an inevitable part of this transition. In later research, the notion of identity crisis was substituted by the notion of moratorium in two distinct ways. First, adolescence was defined as a psychosocial moratorium, a period in which adolescents had time to make important life choices and find a personal identity. Second, moratorium was defined as a psychological state: a period of high uncertainty and feelings of crisis about the self (Marcia, 1966). In this way, Eriksonian thinking and subsequent identity research contributed to defining adolescence as a period of turmoil and crisis.

Mental disorders: emergence and peak in adolescence

Thirty years of research on developmental psychopathology have clearly shown that adolescence is a critical period for the emergence and peak of mental disorders. Anxiety disorders (especially generalized anxiety symptoms, Nelemans et al., 2014b), mood disorders, schizophrenia, and substance use all emerge in adolescence and peak in various periods of adolescence (Lee et al., 2015)....