![]() Compaction

Compaction![]()

Let’s Cram More into the City

Richard Rogers and Richard Burdett

England is a small country with a large population, the third most densely populated country in the world after Bangladesh and Holland. Yet we continue to believe that the future belongs to the suburbs, or rather to suburban sprawl. Over the past 20 years – under a free-market, laissez-faire planning regime – the built-up area in England has doubled, and we have allowed the development of four million square feet of out-of-town shopping centres. Suburbs, however, are wasteful: they waste land (using up to eight times the amount of a typical urban area) and they waste public money (Figs 1, 2).

The more you move away from a town centre, the less efficient services become. Public transport becomes either more expensive or more scarce (or both), sewers and rubbish collection become inefficient. In the US, it is estimated that about £15,000 of federal subsidy goes into every home built on a greenfield site. In this country, the ‘hidden’ costs of roads, sewers, lighting and services are likely to be much higher. The bill doubles if you take into account the social and physical costs of inner-London deprivation – when people, shops and jobs move out, leaving the poor to live in a desolate ghost town. Suburban houses may seem cheaper to build, and therefore to buy, but this is because their price does not reflect their true environmental cost.

Fig. 1. Old model of wasteful housing: London County Council ‘overspill’ estate at Borehamwood, with extravagant public space. ‘No Ball Games’ says the notice

Fig. 2. New model of wasteful housing: soulless brick boxes in a rural environment, Stockton, Warwickshire. (Martin Bond/Environmental Images)

High-density environments, by contrast, provide the critical mass to make public service work more effectively. They bring a sense of cohesion and community that contributes to safety and civic pride – what De Tocqueville called the ‘habit of association’. They can help generate the mix of uses, the sense of security and the quality of public spaces that make urban living attractive, with shops lining the streets and homes overlooking landscaped spaces, parks and playgrounds. They have the potential to be ecologically sustainable, economically strong and socially inclusive.

It is against this background that we should consider the projected need for 3.8 million new households – the equivalent of two cities the size of London – by 2016. This is not the result of population growth. The vast majority (about 85%) of new homes will be for single people, reflecting a fundamental shift in the way we live. People live longer and leave home earlier; they delay marriage; families break up more often. So we need more alternatives to the traditional family house. We cannot continue to provide the same type ‘house’ unit for a single person, as we did for six people (in the 1930s) and for four people (in the 1950s and 1960s). The private sector has already recognised this trend: apartments now account for 20% of rented accommodation, against 10% in 1980.

Fig. 3. Old slum housing, 1911: filthy but lively

Fig. 4. New slum housing, 2000: filthy and unsociable

It is widely assumed that most of the new homes must be in suburbs or on greenfield sites, because that is what people will demand. People, it is argued, do not like living in overcrowded, noisy cities: they have abandoned towns and cities in droves over the past 30 years. But if the urban environment is attractive and well cared for, it can attract people of all incomes and classes. If it is brutal, people want to move out. The long exodus to the suburbs is not driven by a fatal attraction to suburban lifestyles. The ‘push’ factor is as strong as the ‘pull’. Poor quality of life, bad schools, fear of crime, congestion and pollution are the main reasons why people leave (Figs. 3, 4).

The planning debate – about the need for new homes and where to put them – is often discussed as though it were merely about saving the countryside. But it is also about saving our cities. It is about tackling poverty, too, since the government’s Social Exclusion Unit has found that poverty can be addressed only if it is tackled together with area dereliction. For all these reasons, the forthcoming publication of the government’s white paper on the future of urban areas will be a critical moment.

The physical state of our cities and the new types of housing demand point to the same solutions. Because of their industrial past, most English cities are scarred by vast tracts of derelict land and empty buildings – redundant gasworks, railway goods yards, abandoned warehouses. These ‘brownfield’ sites, often near city centres and close to public transport, are perfectly placed to accommodate the type of housing required by single people. They provide the opportunity to create compact and sustainable urban communities with good schools, well-designed homes and public spaces that will even attract families with children back to the city. The government has set a target of building 60% of the projected 3.8 million new households on this type of recycled urban land, leaving the balance, most probably, to be built on rural land.

It is our view that this target should not only be adhered to; it should, and could, be surpassed to give cities a real chance. Far from seeing the need to build such a large number of new homes as a problem, we should see it as an opportunity – to repair our torn and tattered cities and create a truly sustainable urban economy.

We tend to assume that high-density living is bad. But different social, economic and cultural conditions support very different levels of density. High-value, high-density neighbourhoods – such as London’s Belgravia or New York’s Park Avenue, which are five or ten times more intensively developed than typical urban areas – work as well for their inhabitants as the lower density London areas of Hampstead Garden Suburb or Blackheath (Figs 5, 6).

Large parts of desirable Georgian London, Bath or Edinburgh are built to densities between 100 and 200 dwellings per hectare (roughly the size of a football pitch). Many attractive settlements – such as rural villages in Cornwall with two storey terraces at 60 dwellings per hectare – have higher-density centres arranged around a village green or public space surrounded by shops, homes and local facilities. These areas work for people from different economic, ethnic and social backgrounds. Even the Town and Country Planning Association, which pioneered the Garden City movement at the turn of the last century as a reaction to the overcrowding of Victorian cities, recommends a minimum of 40 dwellings per hectare. Yet, over the last ten years, all new development in England has been built at an average of 23 dwellings per hectare. This is an extremely low figure, and planning guidance has recently changed to recommend higher development densities. But we could go further; many successful urban developments, old and new, have been built to much higher densities than the ones we currently design.

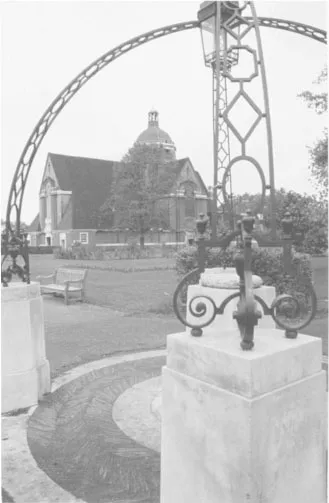

Fig. 5. The centre of Hampstead Garden Suburb: elegant but lifeless

Fig. 6. Fifth Avenue, New York: messy but vital

When densities are low, the quality of public space suffers. The sense of enclosure and protection that we admire in traditional cities disappears. The realm of the pedestrian is taken over by the need of the car – garages, parking spaces, turning circles and bollards replace the vibrancy of the lively street and square. In a typical compact city such as London or Newcastle, tarmac makes up about 15% of the total amount of land. In a typical 20th century American city, based on freeways and suburban sprawl, this figure easily reaches 55%.

Even a modest increase in development density – adding an extra room to a five-bedroom house, or one floor to a two-storey building – would dramatically alter the equation between the number of housing units and the amount of land they take up, thus allowing us to preserve far more countryside. But we are nowhere near breaching the limits of acceptable living through higher densities. An increase of 50% or even 100% in present densities would create more contained neighbourhoods, but without the remotest risk of overcrowding or ‘town cramming’. In fact it is impossible to think of a recent development in England that anyone could reasonably describe as being crammed. On the contrary, in many underdeveloped areas – from Liverpool to Aylesbury – densities are so low that they do not create any sense of continuity or community. In east Manchester, for example, the density has dropped tenfold in the space of just one generation and the area has become derelict.

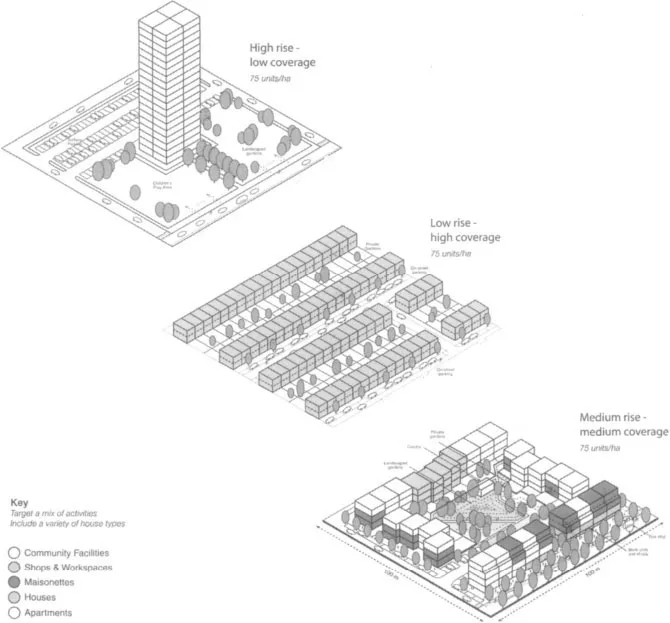

Fig. 7. ‘Three ways of achieving the same density’, from the Urban Task Force Report. (Andrew Wright Associates)

Density has little to do with overcrowding or town cramming. It has everything to do with design of the environment: the balance of massing, light and space. By controlling the way buildings are arranged around public spaces, by ensuring that privacy is guaranteed and noise levels contained, it is possible to create attractive living environments, and to develop stronger and more vibrant communities (Fig. 7).

To solve the town/country problem, then, we must start at the centre of our cities. We must use all available land – brownfield or simply leftover spaces – in a sustainable way. Many of our existing suburbs could be ‘retrofitted’ with new facilities and new residents who would bring activity and spending power to existing communities. More local shops and amenities should be placed near improved public transport hubs within walking distance of homes and houses in areas with spare capacity. There are encouraging signs that the tide is beginning to turn. Parts of Manchester, London and Leeds are beginning to enjoy an ‘urban renaissance’ with a greater influx of single people and childless couples moving back to well-designed homes near public transport, social and commercial facilities.

Last year, the London Planning Advisory Committee carried out an important study on urban capacity. Its pioneering work demonstrated that there is much more space for new housing in London than had previously been calculated. It identified small leftover spaces, urban backlands and larger windfall sites (sites that have not been identified in surveys), and calculated that, in all, London has room for the creation of 570,000 extra homes. At a stroke, this would absorb almost the whole of the capital’s projected demand for new housing.

The same may well apply to the south-east as a whole. Apart from those sites earmarked for planning development, there might be no need to touch any more greenfield land in the so^th-east until well into the 21st century.

This approach could – and should – be extended to the rest of the country. Simply by taking on board the large number of windfall sites in English towns and cities, the amount of available urban land could be increased by 30% or even 50%.

If you then increased development densities, it follows that by far the greatest part of new housing could be built on recycled urban land. Under these conditions, it is hard to argue in favour of building on greenfield land at all.

But England is a divided country. The bulk of redundant industrial land lies in the cities of the north and the Midlands, while, because of its greater wealth and population, the greatest pressure for new housing development is in the south-east. We need a national strategy to strengthen existing towns, cities and villages throughout England. Regional balance is critical to achieving a sustainable economy.

The government, then, should certainly stick to its target of building 60% of new housing on brownfield land. But we believe that ministers should raise their sights and give our cities a real chance. Unless we act soon, it will be too late. Of the greenfield land allocated for development over the next 20 years, as much as 90% has been banked by developers, giving at least 650,000 houses already earmarked for construction in rural areas. That is not only bad for the countryside; it is bad for cities, which will lose even more people.

To achieve the urban renaissance, we need to take some tough decisions. In some cases, we need to reconsider planning applications and modify permissions – encouraging higher densities or a greater mix of uses – before construction is allowed to go ahead. We should not allow low density, residential developments on greenfield land to proceed, if the political will and the market demand to sustain something better is there. Releases of greenfield land for development should be checked, or even reversed in special conditions.

This cannot be achieved by restrictive or punitive measures alone. Fiscal incentives, such as tax breaks for brownfield development and recycled buildings, will help tip the balance. We should also be wary of the precision of the actual projections, as changes in demographic and migration patterns may radically alter the number of households we actually need. This is why we need a far more flexible approach to planning, an approach that would allow us constantly to monitor change and recast our plans accordingly.

If we continue to plan new housing up and down the country at unsustainable levels of 23 dwellings per hectare, we will continue to devour the countryside at an alarming pace, with dramatic social and environmental consequences. If instead we create well-designed and well-managed neigh-bourhoods at higher densities, by far the greater part of the new housing could be absorbed on recycled urban sites.

The acclaim for the newly opened Tate Modern, on the site of London’s former Bankside power station, has shown how, through a combination of leadership, investment and co-operation, new life can be breathed into old buildings and declining urban areas. In Walsall, Salford and Glasgow, new initiatives are having a similar impact. But we need to go much further to rescue our cities and save our countryside.

If the public were offered the chance to live in the contemporary equivalent of a spacious Georgian terrace, with tree-lined streets and landscaped parks, beautiful buildings and public spaces, we believe they would take it. We believe they would be all the more likely to do so if they were guaranteed access to public transport, good schools and other public amenities. If such areas also offered safety and a strong sense of community, we believe people would flock back to our town and city centres.

![]()

Capitalism and the City

Richard Sennett

This is my inaugural lecture at the London School of Economics.1 Occasions of this sort are meant to be reflections on a scholar’s realm; for me, this means discussing the state of the modern city, and of the field of urban studies. What I have to say applies as much to sociology, geography, and economics as it does to the visual investigations which lies at the heart of the LSE’s Cities Programme.

My theme is the relationship of capitalism and the city. The conditions of capitalism are very different today than they were a century ago, when the formal discipline of urban studies began. In my view, we have yet to catch up as scholars with these changes in reality.

Urban Virtues

Let me begin, with a certain amount of trepidation, by stating flatly what is the human worth of living in a city, what is its cultural value. I think there are in fact two urban virtues which made it worthwhile to live even in badly run, or crime infested, dirty or decaying urban places.

The ...