![]()

Part I

Disintegration, 1980–1991

![]()

Chapter One

Political Debate, 1980–1986

I have given this book the title Balkan Babel because I have felt that the biblical story of the Tower of Babel bears a certain allegorical resemblance to the story of Yugoslavia. In the case of Babel, the people of the area had largely friendly and cooperative relations over a period of time. There were no significant rivalries dividing them, let alone ancient tribal rivalries or hatreds. Quite the contrary. They therefore decided to unite in erecting a great tower, undertaking what proved to be an ambitious project. But as the Book of Genesis tells us, soon after they had embarked on this joint project, they found themselves speaking different languages, with the result that work on the great project broke down. The story of Babel may be read, thus, as a story of the failure of cooperative action.

In the case of Yugoslavia, a state founded in 1918 as the kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, the peoples of the area—Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, and others— had had largely friendly and cooperative relations (with the exception of Serb-Albanian relations from about 1878 onward, where tensions were worsened by Serbia’s annexation of Kosovo in the course of the First Balkan War of 1912–1913). There was nothing of the order of tribal rivalries dividing the peoples of the Yugoslav kingdom, let alone ancient tribal rivalries or hatreds. Serbs and Croats in Habsburg-ruled Croatia had actually formed a political coalition in the early years of the twentieth century, and the wartime dialogue between the London-based Yugoslav Committee and the Serbian government-in-exile allowed for some optimism about prospects for future cooperation. Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Montenegrins, and others therefore decided to unite in erecting a common state, undertaking what proved to be an ambitious political project. But as the historical record reveals, soon after they had embarked on this joint project, they found themselves speaking different political languages. The Croats spoke the language of federalism. The Serbs spoke the language of centralism. They proved unable to find a common political language, and by 1929 the system suffered its first major breakdown.

Over the years, all sides came to feel wounded: Serbs by Croats’ opposition and complaints, later by the Ustaša massacres, still later by the controversies of the Croatian Spring of 1970–1971; Croats by the discrimination they suffered from the very beginning, by the assassination of Croatian Peasant Party leader Radić in 1928, later by the Chetnik massacres, still later by the repressive policies of Uprava Državne Bezbednosti (UDBa, the State Security Administration, i.e., secret police) chief Aleksandar Ranković; and one could itemize as well the wounds felt by other peoples of Yugoslavia. The wounds left scars—scars that never completely healed, not because they were ancient but, on the contrary, because they were relatively fresh. The story of Yugoslavia is a story, thus, of the failure of political cooperation.

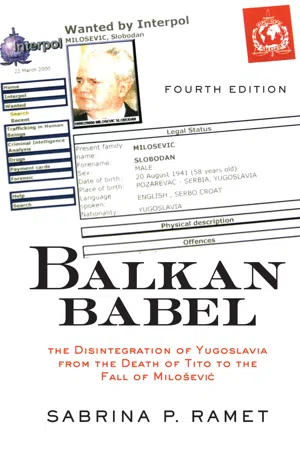

But why did the Yugoslavs fail to erect their Tower of Babel? The answer, for me, lies in their failure to solve the problem of legitimation, their failure to devise a political formula which would impress the decisive majority of the country’s citizens, in both objective and subjective terms, as being basically legitimate. It was for these reasons that I wrote, in the first edition of this book, that Yugoslavia was “beset with problems from the time of its establishment in 1918, and one may quite accurately say that no sooner was the multi-ethnic state constituted than it started to fall apart” (1st ed., p. 38). I shall have the occasion elsewhere to describe the difficulties experienced by the Yugoslavs in this regard from 1918 to the present. My purpose in this book is to tell the story of Yugoslavia’s disintegration, the story of its failure, from the death of President Josip Broz Tito in May 1980 to the fall of President Slobodan Milošević in October 2000 and the resounding electoral victory of the democratic opposition coalition in the Serbian parliamentary elections of December 2000.

Josip Broz Tito ruled Yugoslavia for some thirty-seven years, guiding the country through a major crisis in relations with the Soviet Union, steering it through four constitutions, and creating a political formula centered on self-management (in the economy), brotherhood and unity (in nationalities policy), and nonalignment (in foreign policy). Despite the internal crises which shook the country in 1948–1949, 1961–1965, and 1970–1971, Tito created a network of institutions which many hoped would prove stable and resistant to disintegrative change. Yet, for reasons quite different from and independent of those affecting other countries in Eastern Europe, Yugoslavia’s political institutions ultimately proved vulnerable to pressures for change. Such pressures built up gradually and steadily from the grass roots, from the intellectuals, feminists, environmentalists, pacifists, and liberals. Political change was adumbrated first in the cultural sector and borne along by small independent grassroots organizations.

As noted, Yugoslavia experienced considerable problems from its inception in 1918. This was no surprise given the lack of consensus on the fundamental principles of state. Over the course of its seventy-year history, Yugoslavia lurched from crisis to crisis, abandoning one unstable formula for another. Finally, in the course of 1989–1991, the unifying infrastructure of the country largely dissolved. In its first incarnation as the interwar Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, 1918–1941 (renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929), the country experimented with pseudodemocratic Serbian hegemony, royal dictatorship, and Serb–Croat codominion.1 The system failed to ground itself on legitimating principles and left a legacy of bitterness which fed directly into the internecine conflicts of World War II (1941–1945 in the Yugoslav lands). That war saw the occupation of parts of Yugoslavia by German, Italian, Bulgarian, and Hungarian troops and the erection of quisling regimes in Croatia (under Ante Pavelić) and Serbia (under Milan Nedić).2 More than a million persons died in the course of the war, and additional seeds of bitterness were sown. Although Tito and his Communist comrades talked endlessly about the need to create “brotherhood and unity” and recognized quite clearly the dangers inherent in national and religious chauvinism, they lacked a clear vision of social tolerance, without which their efforts ultimately foundered.

Tito’s Partisans, winning accolades in engagements against occupation and quisling forces, emerged as the only strong force in Yugoslavia at war’s end. Communist rule made its debut with brutality when between 20,000 and 30,000 Serb Chetniks and Slovene Home Guards (who had tried to surrender to British forces only to be turned over to the Partisans) were massacred by Partisan forces, along with some 36,000 Croats and 5,000 Muslims.3 The Communists lost no time in suppressing reemergent political parties after World War II4 and set about introducing a Soviet-style system. Indeed, Yugoslavia’s Communists started out as run-of-the-mill Stalinists. The early years followed the standard formula of arrests, show trials, forced collectivization, attacks on the churches, and erection of a strict central planning system. But their expulsion from the Soviet bloc by Stalin in June 1948 forced them to find their own formula and, in the process, gave them a new image. Tito became the new David to Stalin’s Goliath and came to be seen as a hero in the West. With American and British assistance, Tito’s Yugoslavia weathered severe food crises in 1946–1947 and 19505 and, under the pressure of the change in the diplomatic environment as well as internal developments, including the peasant rebellion against agricultural collectivization in the Cazin region in 1950,6 began to demarcate an independent path.

In 1950, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY) introduced the principle of self-management on an experimental basis, promulgating it generally two years later; in the meantime, on 24 November 1951, the CPY Central Committee issued a directive to scrap the collective farm system, blaming the Soviets for providing an example which had proven “completely wrong and harmful in our practice”7 and authorizing the return of farmlands to private ownership. Stalin was so enraged by Tito’s behavior that, in autumn 1952, he had Lavrenti Beria, the head of the KGB, develop a plan to assassinate the Yugoslav leader; the plan foundered as a result of uncertainties associated with Stalin’s death in March 1953.8 Although Tito’s example undoubtedly had given some encouragement to Hungarian Prime Minister Imre Nagy and his fellow revolutionaries in Hungary in 1956, Nagy’s rapid gravitation toward political pluralism unnerved Tito, who, as recently opened archives reveal, told Khrushchev he felt military intervention was necessary and may even have developed contingency plans of his own to employ Yugoslav military force to restore “socialism” in Hungary.9 Meanwhile, Yugoslav reformism continued. By 1958, at its Seventh Congress (in Ljubljana), the by now renamed League of Communists of Yugoslavia (LCY) was boasting, much to Soviet annoyance, of its uniquely progressive model and offering it for general emulation.10

In the 1960s and 1970s, it appeared that Yugoslavia had finally found the key to solving its most important problems. Aleksandar Ranković chief of the secret police, had resisted reform, but was stripped of his power in July 1966.11 Decentralization, which had quietly begun as early as 1952, but which had picked up momentum as a result of the constitution of 1963, gathered steam after RankoviN’s fall. This formula, which established a network of quasi-feudal national oligarchies and entrenched their power in the constituent republics of the Socialist Federated Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), created the institutional fissures along which Yugoslavia would break up; indeed, without the quasi-confederal system of republics, it is unlikely that the SFRY would have fallen apart as soon or as relatively easily as it did. So concerned were the Yugoslav reformers of the late 1960s to build up the infrastructure of the republics that they saw to it that the Federal Assembly adopted a new law on national defense on 11 February 1969, granting the republics the authority to form local territorial militias.12 Coming partly as a response to the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the new law also reflected the decentralist convictions of Titoist reformism; the militias created by this law would prove critically important in the case of Slovenia in 1990–1991.

The constitution of 1974 seemed to provide political s...