![]() Part 1

Part 1

Cultural Mixing![]()

1

St. Anne Imagery and Maternal Archetypes in Spain and Mexico

CHARLENE VILLASENOR BLACK

Believed by Catholics to have been the mother of the Virgin Mary and grandmother of Jesus, St. Anne enjoyed remarkable devotion in sixteenth־, seventeenth-, and eighteenth-century Mexico. Numerous colonial hagiographies, sermons, and devotional texts, as well as countless visual images, lauded her as the “Mother of the Mother of God” and the “most holy Grandmother of Jesus.”1 Many Mexican villages, chapels, churches, and missions were named after her. Today Anne remains a venerated saint in Mexico. Anthropologists recently documented thirty-one communities that celebrate her July 26 feast day, plus forty additional locales where Mary’s Nativity is observed on September 8.2 Thus, after the Virgin Mary, St. Anne is the most celebrated female holy person in Mexico. What is so remarkable about St. Anne’s vigorous following in Mexico is that her cult attained popularity despite Spanish Church and Inquisition attempts to squelch such devotion. In fact, St. Anne’s cult flourished in colonial Mexico at the very time it declined in importance in Spain. Why did the cult of St. Anne prosper in Mexico as it dwindled in Spain? Positing answers to that question, which take into account the creation of new hybrid cultural forms in colonial Mexico, is the goal of this chapter.

As in the case of many other important Catholic saints, the Gospels make no specific mention of St. Anne. The first textual references to her appear in the apocryphal Proto evangelium of St. James, from about 150 C.E., which opens with the story of Anne and Joachim as a prelude to the Nativity of Mary. The widely circulating Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, written in about 1260, elaborated on and popularized the Protoevangelium and other apocryphal tales about Anne, such as the Gospel of the Pseudo-Matthew and the Nativity of Mary. These early sources encapsulated the medieval construction of St. Anne’s life. After twenty years of marriage to St. Joachim, a union that produced no offspring, an aged St. Anne miraculously conceived Mary during an embrace with her husband at the Golden Gate of Jerusalem, a wondrous series of events memorialized by the artist Giotto in his Arena Chapel frescoes. The Golden Legend also popularized the belief, apparently dating from the ninth century, that St. Anne was thrice married. According to this version of Anne’s vita, after Joachim’s death, she remarried two additional times, to men named Cleophas and Salome. With each husband she bore a daughter, all three of whom were named Mary. Belief in Anne’s three marriages, or the trinubium, fostered by circulation of the Golden Legend, became widespread in Europe.3

In the West, St. Anne rose to prominence in the late Middle Ages. Her cult reached its height between 1450 and 1550, according to the scholars Kathleen Ashley and Pamela Sheingorn, authors of an important study of St. Anne as European cultural symbol.4 William A. Christian Jr.’s research on Iberian popular devotion confirms the importance of St. Anne’s cult in sixteenth-century Spain. His analysis of King Philip II’s relaciones topogrdficas of 1575-80 in New Castile, a printed census of Spanish towns that included questions on devotional practices, demonstrates that after the Virgin Mary, St. Anne was the most popular female saint in sixteenth-century Spain.5 She was widely hailed as the patron of the childless, women in childbirth, as well as a universal intercessor capable of intervening during outbreaks of the plague or threatening weather. In 1584 Pope Gregory XIII mandated universal observance of St. Anne’s July 26 feast day in the Roman Catholic Church. Clearly, the lack of canonical church writings on St. Anne did not discourage devotion to her figure.6

Early Modern Spanish and Mexican devotional writers explained the absence of Gospel references to St. Anne by suggesting that just like the Holy Grandmother’s womb, which had held the secret treasure of the most pure Virgin, the Bible, too, contained hidden treasures.7 These treasures were revealed by sermons, devotional texts, and images of the saint. Five different image types representing St. Anne enjoyed popularity in Spain, all of which were transferred to Mexico during the colonization. These were the Holy Kinship and the Holy Family, St. Anne Triplex, the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, depictions of Sts. Anne and Joachim together, and St. Anne teaching the Virgin Mary to read. Visual readings of these various images demonstrate that all thematize Anne’s maternality, to use Julia Kristeva’s term denoting idealized fantasies of motherhood.8 Thus all focus on her roles as mother, grandmother, and matriarch, depicting scenes of pregnancy, birth, and maternity.

According to one interpretation, late medieval portrayals of the Holy Kinship valorized the women of Jesus’ family.9 The scene represents the numerous members of the extended Holy Family, including the Virgin and Child, St. Joseph, and St. Anne, as well as Mary’s apocryphal sisters, their husbands, and six children. A print of the theme forms the frontispiece to one of the most influential premodern Spanish hagiographies of St. Anne, Juan de Robles’ La vida y excelencias y miraglos de santa Anna y de la gloriosa nuestra señora santa maria fasta la edad de quatorze años: muy deuota y contenplatiua nueuamente copilada (Seville: Jacobo Cromberger, 1511). A painting by Hernando de Esturmio of 1549 in the parish church of Santa María de la O in Sanlúcar de Barrameda also depicts the subject.10 Typically, the Virgin, Child, and St. Anne appear in the foreground on a throne attended by the other daughters and their children. Their various husbands, all rendered as diminutive forms in hieratic scale, cluster together in the background, peering over the throne. According to Sheingorn, proliferation of the Holy Kinship was linked to attempts to trace Jesus’ genealogy through matrilineal descent as well as to the valorization of the matriarchal extended family in Europe.11

Depictions of St. Anne Triplex, or selbsdritt, as it is more commonly known in northern European art, consist of an oversized St. Anne holding her daughter, rendered in hieratic scale, upon her lap, the latter with the infant Jesus in her arms. Such images serve as a synecdoche, or shorthand notation, for the extended clan of the Holy Kinship. Examples by Spanish artists are numerous in the fourteenth, fifteenth, and the first half of the sixteenth centuries.12 By using hieratic scale, in which the most important figure is rendered as the largest, artists glorified Anne as the Holy Family’s matriarch and emphasized Jesus’ matrilineal descent.13

Scenes of the Nativity of the Virgin, which depict Anne after giving birth, glorified the saint’s position as the mother of Mary as they provided visual testimony to her traditional role as patron of women in pregnancy and childbirth. The subject appears frequently in sixteenth-century Spanish art. Examples include paintings by Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina (Valencia, cathedral, 1507-10) and Juan de Borgoña (Toledo, cathedral, 1509-11), among many others. In Borgoña’s fresco, St. Anne reclines in bed, weary from the labor of childbirth. An attendant offers a bowl of food to the saint, perhaps the caldo or soup recommended by Spanish medical doctors to be fed to women after giving birth. Frequently, female attendants prepare to bathe or swaddle the newborn Mary. Artists often included St. Joachim as an onlooker. Comparison between Early Modern Spanish medical texts and depictions of the Nativity of the Virgin suggest that such images reflect actual postpartum practices. Indeed, an important Spanish medical text from 1580 employed a print of the Nativity of the Virgin as its frontispiece.14

The earliest images of the Holy Grandparents, Sts. Anne and Joachim, together, appear to have been by-products of the cult of the Immaculate Conception, which rose to importance in the twelfth century. Depictions of Anne and Joachim embracing in front of the Golden Gate of Jerusalem attempted to visualize Mary’s miraculous conception. Examples of the scene are plentiful in sixteenth-century Spanish art and include paintings by Pedro Berruguete (Becerril de Campos [Palencia], Santa María), Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina (Valencia, cathedral, 1507), Juan de Borgoña (Toledo, cathedral), Antonio de Comontes (Toledo, Concepcion Francisca), Juan Correa de Vivar (Toledo, Santa Isabel de los Reyes), Vicente Macip (Segorbe, cathedral, c. 1530), and others.15 In the sixteenth century, artists cut down depictions of the Tree of Jesse to depict only Anne, Joachim, and Mary, a new image designed to give visual form to the Immaculate Conception.16 Suzanne Stratton has identified the first such depiction, a stained glass window in Granada Cathedral from about 1528.

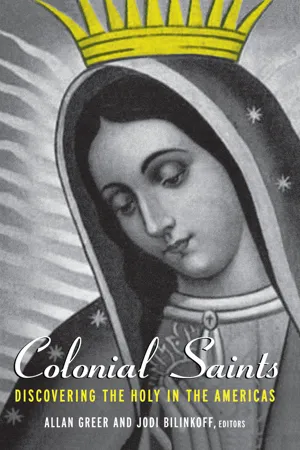

Although the theme of St. Anne teaching the Virgin to read appeared infrequently in Spanish sixteenth-century art, three notable examples date from the seventeenth century, by Juan de Roelas (Seville, Museo de Bellas Artes, 1610-15), Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Madrid, Museo del Prado, c. 1650) (figure 1-1), and the sculptor Juan Martínez Montañés (Seville, Convento de Carmelitas de Santa Ana).17 All three artists depicted the child Mary seated at her mother’s knee, before an open book. In the 1700s the subject became popular on both sides of the Atlantic, perhaps as a result of the Spanish Enlightenment promotion of reading.18

Figure 1-1 Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, St. Anne Teaching the Virgin Mary to Read, circa 1650. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

These various images, numerous religious texts, and the record of popular devotional practices provide eloquent testimony to Anne’s position of honor in sixteenth-century Spain. St. Anne’s heyday in Spain, however, was about to end. Church reformers’ writings as well as the visual record suggest that attempts to suppress her cult in Spain began shortly after the Council of Trent (1545-63). The Spanish campaign to downplay St. Anne’s cult is surprising, particularly since Pope Gregory XIII mandated universal observance of her feast day for the entire Roman Catholic Church in 1584. Because of the unauthorized, vernacular nature of Anne’s cult, however, some delegates at the Council of Trent, the church council convened in response to the Protestant Reformation, as well as later Tridentine reformers, regarded popular enthusiasm for St. Anne with suspicion.19

The first image to disappear from Spanish artists’ repertoires was the St. Anne Triplex. Although I have found no specific critiques of the image or instructions to artists to cease its depiction, one imagines that commissions for the type dwindled after the Council of Trent for a variety of reasons. Reformers’ call for a new religious art—an art of clarity that placed a premium on the creation of reality effects—surely caused interest in the hieratic, abstract theme of St. Anne Triplex to decline. Concerted attempts by Spanish theologians to trace Jesus’ genealogy through his foster father, St. Joseph, may have further discouraged patrons from commissioning images designed to pictorialize Jesus’ female forbears.20

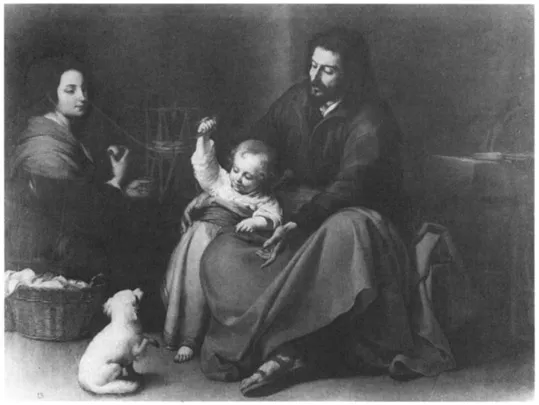

The disappearance of St. Anne Triplex, its trio of grandmother, mother, and son, a referent of the extended clan, heralded the decline in Spanish depictions of the Holy Kinship. By the seventeenth century, Spanish Holy Families had undergone a major metamorphosis. Artists produced fewer scenes of the Holy Family with the Virgin’s parents, Sts. Anne and Joachim, and concurrently they focused on the nuclear family. St. Joseph began to dominate the scene.21 Murillo’s Holy Family with a Little Bird (Madrid, Museo del Prado, c. 1650) (figure 1-2) exemplifies the newly reconfigured patriarchal nuclear Holy Family. In Murillo’s painting, the powerful figure of the young St. Joseph is the focal point as he keeps a vigilant eye on the divine toddler, at play with the family dog. The demure Virgin, the traditional focus of such scenes, looks on modestly from the left background, winding thread for spinning.

In fact, after the Council of Trent, Church reformers explicitly banned representations of the Holy Kinship because they included the apocryphal “sisters” of Mary from St. Anne’s second and third marriages and urged artists to depict only the nuclear Holy Family. The censors fretted about the historical “authenticity” of these sisters, a typical concern after the Council of Trent, but also about Anne’s three husbands. Reformers were eager to quash the idea of the trinubium. At best these multiple marriages presented an unseemly view of the mother of the mother of God. At worst, they cast doubt on the sanctity of matrimony and its status as a sacrament, a major issue of debate with Protestants. Thus, the trinubium, deemed unorthodox, was stricken from hagiographies.22 The Spanish artist, art theorist, and veedor, or inspector, for the Spanish Inquisition, Francisco Pacheco, addressed the problem explicitly in a section of his treatise TheArtofPaintingûûzà “A Painting of St. Anne No Longer in Use”:

At one time, the painting of the glorious St. Anne seated with the most holy Virgin and her Child in her arms and accompanied by her three husbands, her three daughters, and many grandchildren, as it is found in some old prints, was very valid, of which today the most learned do not approve and which the most judicious painters justly reject, because, as Tertulian said: “Time increases wisdom and uncovers truths in the Church.” Thus, today we see favored as certain and secure truth the single marriage of St. Anne and St. Joachim.23

Figure 1-2 Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Holy Family with a Little Bird, circa 1650. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Pacheco also weighed in on the appropriate portrayal of the Nativity of the Virgin, comparing several sixteenth-century variations of the scene. The great detail provided by Pacheco suggests the popularity of the subject in sixteenth-century Spain as well as the varia...