This is a test

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Twentieth Century Industrial Archaeology

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book examines the industrial monuments of twentieth- century Britain. Each chapter takes a specific theme and examines it in the context of the buildings and structure of the twentieth century. The authors are both leading experts in the field, having written widely on various aspects of the subject. In this new and comprehensive survey they respond to the growing interest in twentieth-century architecture and industrial archaeology. The book is well illustrated with superb and unique illustrations drawn from the archives of the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England. It will mark and celebrate the end of the century with a tribute to its remarkable built industrial heritage.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Twentieth Century Industrial Archaeology by Michael Stratton,Barrie Trinder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture générale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter one

Introduction

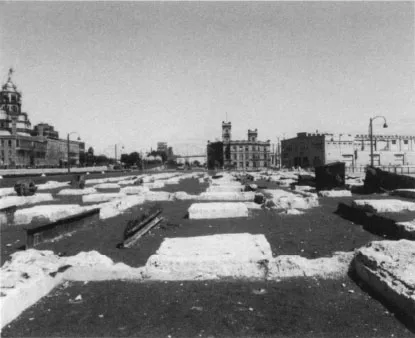

‘Archaeology’ and ‘the twentieth century’ are terms that do not easily co-exist. ‘Archaeology’ has associations with Stonehenge and with the excavation of Roman villas, and ‘industrial archaeology’ is traditionally linked with the period between the Seven Years War and the Great Exhibition, with Cromford, Blaenavon, New Lanark, the Albert Dock and Swindon. Yet one twentieth-century archaeological site of some importance in British history was by the 1990s already displayed in much the same way as the Roman villa at Chedworth or the foundations of Richard Arkwright’s second mill at Cromford. In the Old Port of Montreal visitors can observe the outline of the concrete foundations of a thirty-two-storey grain elevator erected in 1912, together with associated fragments of rubber belting, twisted steelwork and rusting electric motors. The conserved ruin conveys a vivid sense of the scale of the Canadian grain trade and, indirectly, of its impact on Great Britain, and provides enlightening evidence of the new materials of the early years of the century. The elevator encapsulates the fundamental, if elementary, concept on which this book is based – that our understanding of the twentieth century is increased by an awareness of its archaeology, of the artefacts, images, structures, sites and landscapes of the past 100 years.

1.1 The site of Elevator No. 2 in the port of Montreal, a thirty-storey concrete structure, built in 1912, when Montreal handled more grain than any other port in North America. The remains of the elevator are preserved as an archaeological site by Le Vieux Port de Montréal.

(Photo: Barrie Trinder)

1.2 The buildings on the Pier Head at Liverpool illustrate the constructional possibilities of the early twentieth century. The Liver Building (left) was designed, by W. Aubrey Thomas, on the Hennebique system, and built between 1908 and 1911. The cladding is of grey stone. The Cunard Building (centre) was built in 1915 with a Truscon frame. The headquarters of the Mersey Docks & Harbour Board (right) was built in 1907 to the design of Arnold Thornley, with a Baroque dome supported on a steel frame supplied by Dorman Long.

(Photo: A. F. Kersting)

The book has several starting-points. The first is the proposition that our understanding of any event or sequence of events is increased by an awareness of its physical context, something which is lacking in many conventional twentieth-century historical studies, for example in the kind of business history written from a head-office viewpoint, that conveys no sense of a company’s factories, shops or warehouses. Yet events took place in real landscapes, in structures which can be studied either in the field or through maps and pictures. Factories produced real products which survive, if nowhere else, in museums. Houses and flats were built for real people who exercised in them their aesthetic taste, made love, raised children, and installed appliances made in real factories. Some historians follow conventional wisdom in deploring certain aspects of the twentieth century – the monotony of work in car factories or the horrors of living in tower blocks, for example. We have tried to write from first-hand experience of sites and landscapes, and have consciously taken a sceptical, irreverent and sometimes counter-intuitive attitude to received views of twentieth-century artefacts and places. In this respect we acknowledge as a starting-point the writings of the late Reyner Banham, who was excited by and recognised the merits of Cummings ice-cream vans, container ports and the power stations of the Trent Valley.1

We are consciously attempting to work in the tradition established in the 1950s by Maurice Beresford and W. G. Hoskins, that archaeologists and historians should help people to understand their everyday surroundings. Beresford, chronicler of industrial Leeds and an inspiration for all who study history on the ground, wrote in 1957 about journeys along boundaries, among deserted villages, through parks and to Elizabethan marketplaces. We offer journeys along by-passes, among ordnance factory buildings, through industrial estates and to Elizabethan power stations, and share with Beresford some expeditions to new towns.2 Similarly we are inspired by the work of the late W. G. Hoskins. We share his pleasure in the English landscape, in trying to recognise ‘every one of its details name by name, in knowing how and when each came to be there, why it is just that colour, shape or size, and not otherwise, and in seeing how the various patterns and parts fit together to make the whole scene’. Hoskins saw the landscape in musical and architectural terms, and strove ‘to isolate the themes as they enter, to see how one by one they are intricately woven together and by what magic new harmonies are produced … [to] perceive the subtle variations on a single theme’. We do not share Hoskins’s view of the twentieth century. We are unhappy with his opinion that the word ‘overspill’ is as ‘beastly as the thing it describes’ – he would surely not have written ‘the people whom it describes’.3 Whatever the ancient field and settlement patterns obliterated by the airfields of the Second World War, the remnants of runways, accommodation blocks and control towers are monuments to an heroic resistance to Fascism. The England of the Nissen hut, the ‘prefab’ and the arterial by-pass may not be beautiful, but it merits analysis. The Britain of Grangemouth, Port Talbot, Trafford Park, Billingham and Drax has transformed our way of life in the past century, raising most people’s living standards to levels unimagined in 1900. The Britain of Letchworth, Gretna and Roehampton, of the Spitfire, the Queen Mary, the Cheltenham Flyer, the Mini-Minor and the E-type Jaguar, includes themes as harmonious as any to be heard in Hoskins’s more distant centuries. Nevertheless, we are wholly in agreement with Hoskins that the pace of change in the twentieth century was unprecedented, that surging economic growth, whatever its causes, unleashed far-reaching changes in every aspect of material culture.

Our third objective is to provide a context for some of the specialised studies currently being undertaken by industrial archaeologists of particular aspects of twentieth-century history. The royal commissions in England, Scotland and Wales have been responsible in recent years for much innovative recording: of the explosives industry, of road transport, of the monuments of coal mining and the operation of coal mines. Some of the reports of the Monuments Protection Programme have been concerned with sites of recent date relating to industries which are centuries old, like lime-burning, ceramics and non-ferrous mining; and some, like the study of power stations, are concerned largely with the twentieth century. Such studies will in due course change our views of twentieth-century industry. This book is intended to enable them to be seen in a wider setting.

We hope also to identify some of the sites which encapsulate the developments of the last 100 years, and to begin to set an agenda for future investigations. The pioneering works on industrial archaeology of the 1960s and the early 1970s, by the late Kenneth Hudson, and by Neil Cossons and Angus Buchanan, brought to public attention the most significant sites and structures of the classic Industrial Revolution period.4 In the last thirty years our understanding of that period has been increased by studies of textile mills, primitive railways, canals, potbanks, ironworks, domestic manufactures and coalfield landscapes. Following in this tradition, we hope to show why such places as Trafford Park, Letchworth, Dungeness, Clydebank and Bridgend demand our attention and repay archaeological analysis, and why, for reasons of historical scholarship as well as of basic humanity, we should be grateful that Slough was not destroyed by friendly bombs, as envisaged in John Betjeman’s poem.5 Many characteristic features of twentieth-century Britain have already disappeared, or are now represented only by chance survivals, to which we shall draw attention. We hope to take our readers into parts of Britain with which they may not be familiar, areas that may be despised, even by those who live in them. Like Maurice Beresford in 1957, we see our journeys as the starting-points for those of other people.

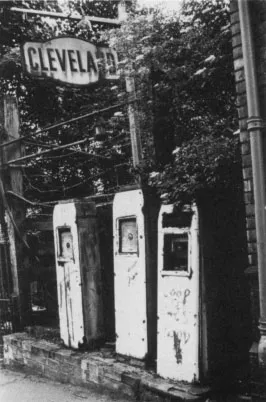

1.3 Derelict petrol pumps with a sign for the long-extinct Cleveland brand of petrol, photographed at Darlaston near Wolverhampton in 1998.

(Photo: Clifford Morris)

Finally, we hope that this study will engage and add an archaeological element to some historians’ debates on twentieth-century Britain. The chapters are centred not on sectors of industry but on historical themes, some of them perhaps historical clichés. We examine, from the archaeological viewpoint, a series of propositions: that twentieth-century industry has been shaped by science and by the international transfer of technology; that the quality of British industrial technology has declined relative to that of other countries; that the two world wars have been decisive factors in the history of the past 100 years; that the inter-war years and the period from 1955 to 1973 were times of ‘great rebuilding’; that the service sector of industry has grown at the expense of the manufacturing sector.

Debates on twentieth-century Britain take place within many disciplines. In the research for this book we have gained understanding from the work of political, social, economic and urban historians, and from historians of architecture, technology and science; from sociologists, planners, architects, engineers, social anthropologists and psychologists.

We owe particular debts to several scholars. Kenneth Hudson not only set an agenda in the 1960s for studying the archaeology of the Industrial Revolution but published in the late 1970s the first studies of twentieth-century industrial archaeology.6 We disagree profoundly with some aspects of Hudson’s approach, but we acknowledge with gratitude his pioneering role. All students of twentieth-century Britain must regard with awe Charles Loch Mowat’s Britain between the Wars, perhaps the best textbook on any period of our island’s history. It shows an awareness of landscape and process with which we have strong sympathies. We admire equally the same author’s classic microstudy of a rural branch railway in the Welsh Borderland.7 Our third particular debt must be to Arthur Marwick, from whose studies of twentieth-century society, and of the impact of war upon it, we have gained much stimulation.8

If, as we contend, our understanding of the development of industry between 1700 and 1850 has, over the past thirty years, been extended by archaeological analysis, it is pertinent to ask how this has been achieved. Some developments have come through straightforward quantification, by bringing together the evidence of maps, documents, pictures and fieldwork and asking how many establishments there were of particular kinds at particular times, by doing what the prehistorian with no evidence other than fieldwork data might do with burial mounds or rectangular enclosures. Our knowledge of textile mills, potbanks in north Staffordshire, domestic weaving premises in lowland Lancashire and ironworkers’ housing in South Wales, to give but four examples, has been profitably enlarged by these means. Second, our understanding has grown by developing typologies.9 Demonstrating that there was a distinct type of medium-lift steam pumping engine has increased our knowledge of the canal system.10 Comparative studies, contrasting evidence from Aberdeen, Leeds, Whitehaven and Shrewsbury, have shown that the majority of the first iron-framed buildings in the textile industry were used for processing flax, and have begun to reveal how flax-spinning complexes were organised.11 Spatial analysis of settlements where domestic and factory production co-existed is revealing much about the process of industrialisation, whether in the spinning and weaving of cotton in Preston, lacemaking in Nottinghamshire, or boot-and shoemaking in Northamptonshire.12 The physical evidence of any period of history is not negated by a profusion of documentary sources. The student of Roman Britain will examine the ruins of Wroxeter as well as the writings of Tacitus. Offa’s Dyke is as effective a testimony to the authority of Saxon kings as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Lincoln Cathedral and Caernarfon Castle as well as the Pipe Rolls and monastic cartularies enrich our knowledge of the Middle Ages. The twentieth century can scarcely be different. All sensible people can agree that archaeological and documentary knowledge should be integrated, and we strive for such integration here. But there is something to be gained from putting ourselves in the position of the prehistorian and asking narrowly archaeological questions – what could we learn about twentieth-century society, if we had no other source of informati...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword by Sir Neil Cossons

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter one Introduction

- Chapter two A new material culture

- Chapter three Industrial revolutions: energy

- Chapter four The international transfer of technology: the case of the food industries

- Chapter five Cars, ships and aircraft

- Chapter six The age of science

- Chapter seven The century of total war

- Chapter eight The great rebuildings

- Chapter nine Changing horizons: the archaeology of transport

- Chapter ten Expanding services

- Chapter eleven Reaching conclusions

- Appendix

- Further reading

- Index of names

- Index of places

- Subject indexes