eBook - ePub

Urban Future 21

A Global Agenda for Twenty-First Century Cities

This is a test

- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Prepared for the World Commission on Twenty-First Century Urbanization Conference in Berlin in July 2000. This book is an entirely new and comprehensive review of the state of world urban development at the millennium and a forecast of the main issues that will dominate urban debates in the next 25 years. It is the most significant book on cities and city planning problems to appear for many years.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Urban Future 21 by Peter Hall,Ulrich Pfeiffer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

The Millennial Challenge

I. The Millennial Challenge

This book opens with a city that was, symbolically, a world: it closes with a world that has become, in many practical aspects, a city

Lewis Mumford (1961) The City in History

The First Urban Century

Two great milestones follow one another: two or three years after the millennium, for the first time in the history of humankind, a majority of the world’s six billion people will live in cities (UNCHS, 1996b).1 Already, the world’s cities are growing in total by more than 60 million – equivalent to the entire population of the United Kingdom or France – each year. Between 2000 and 2025, according to UN projections, as the world’s urban population doubles from 2.4 billion (in 1995) to 5 billion, the proportion that is urban is expected to rise from 47 per cent to over 61 per cent (UNCHS, 1996b).

But this growth will be unequally distributed: the explosive growth is occurring, and will occur, in the cities of the developing world, in Asia, in Africa, in Latin America. In the developed world, the great period of urbanization has already been and gone: here, 76 per cent of the population already live in urban places, and people and jobs are moving out away from the big cities to smaller places. Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States have actually experienced a recent decline in their urban growth rates as people move back from city to farm, for the first time in half a century.

In sharp contrast, at the millennium less than 41 per cent of the population of the developing world live in cities. And here, the process of urbanization is still in full flood. There will be a doubling of the urban population, between 2000 and 2025, in Latin America, in Asia and in Africa – above all in Africa. Caio K. Koch-Weser, then Managing Director of the World Bank, advised Habitat II in Istanbul that ‘By the time of Habitat III in 2015, 27 cities will have passed the 10 million mark, 516 cities will have passed the one million mark and the urban population will have passed the 4 billion mark. Populations will spread beyond metropolitan borders to secondary centers, and far into what are now largely rural areas’ (Koch-Weser, 1996).

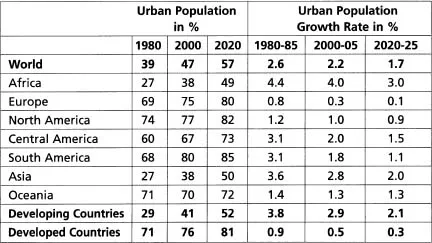

But the developing world, too, exhibits huge differences: already, nearly three quarters of the population of Latin America and the Caribbean is urban, and in some key countries the figures are higher: Argentina (89 per cent urban), Chile (85 per cent urban) and Uruguay (91 per cent urban). In contrast, less than one-third of the populations of Africa and Asia lives in urban areas. The central challenge lies here, in the exploding cities of some of the poorest countries of the world. For it is here that the great urban transformation has recently been occurring, and will continue to occur. In Asia, between 2000 and 2020 the urban percentage will rise from 38 to 50; in Africa, the expected increase is from 38 to 49 (table I.1). Africa – the latecomer to the process of urbanization, with the least urban tradition and the most recent experience of city life – is currently urbanizing at an estimated 4 per cent annually. In Asia the corresponding rate of urbanization is around 3 per cent. China reports up to 130 million surplus workers in the rural areas, a number expected to increase to 200 million by the year 2000. During the 1980s and 1990s, this surplus labour, plus higher-wage jobs in China’s urban areas, especially in the south-eastern provinces, has created one of the most massive migrations in world history; perhaps 100 million have moved from farm to city (Migration News, 1994).

Already, the largest urban agglomerations of all are no longer in the developed world but in the developing world; and here, the scale of urbanization is beyond anything conceivable even in 1950, let alone 1900. During the century just passed, especially in its second half, the cities of the developing world have seen dizzy rates of growth. São Paulo, which in 1900 had a mere 205,000 people, has grown to 16.5 million; Lagos, which as late as 1931 numbered only 126,000, has swollen to over ten million in 1995, though no one is really sure about the true number. By the year 2015, the UN predict that there will be 358 ‘million cities’, cities with a population of one million or more: no less than 153 will be in Asia. And of the 27 ‘mega-cities’, with ten million people or more, predicted for the year 2015, 18 will be in Asia (table I.2).

Table 1.1. Urban population.

Source: WRI, UNEP, UNDP, World Bank (1998).

Urban experts now identify a new phenomenon among these mega-cities: an agglomeration of perhaps a score of cities of different sizes, formerly separate, still retaining a physical identity, but constituting a population mass of 20, even 30 million people, and highly networked. The Pearl River Delta between Hong Kong and Guangzhou is one such cluster that began to emerge in the 1980s; the Jakarta-Surabaya corridor another; Japan’s Tokaido corridor, between Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka, is perhaps the archetypal example. In several of these, the sheer logistical problems – of supplying services, of handling transportation, of waste disposal – are already daunting; they could reach crisis point between 2000 and 2025. Humanity has not been down this road before; there are no precedents, no guideposts.

But significant as is the growth of the mega-cities, we would do well not to be mesmerized by them: in truth, throughout the world, smaller cities grow faster than larger ones, for the quite basic reason that very large organisms can never grow as fast as smaller ones. We will do better to concentrate not on size but on function. Some of the biggest problems occur in relatively small cities in these countries, many of which – above all in Africa – have lower per capita GDP than thirty years earlier, thus compromising the ability of urban managers to provide infrastructure and services to new urban populations.

A Networked Urban World

The new millennium marks yet another urban milestone: not only is this the first urban century, it is the first century in which the world’s city dwellers will form part of a single networked globe.

Three great forces have forged the explosive growth of cities in the century just passed. First, industrialization and its concomitant deindustrialization, which transformed the now-developed world before 1950 and has transformed the developing world since then. In the already-developed world, the proportion of manufacturing workers has dropped throughout the twentieth century, falling around 1990 to between 17 and 32 per cent in advanced countries, and absolute numbers have fallen since 1970; service workers now everywhere constitute a majority, accounting for between 60 and 75 per cent; and informational workers have risen from 20-25 per cent in 1920, to between 35 and 50 per cent around 1990 (Castells, 1996, pp. 209, 282–301 );2 in the developing world, conversely, the proportion of farmers and other primary producers has fallen and the proportion of factory workers has risen. In both cases, with a few sad exceptions, this new international division of labour has brought advantages to everyone: per capita incomes have risen several times in the half century. Second, the transportation revolution, successively in the form of the humble bicycle (still the basic mode of movement in much of the developing world), mass transit and the private automobile; and third, the parallel telecommunications revolution which has dramatically extended from the telephone to the fax and the internet. We could add a fourth factor, political transformation: though less momentous in its urban impacts, decolonization has fostered the growth of new national capitals.

Table 1.2. Mega-cities 1995 and 2015.

| Urban Agglomeration | Population (thousands) | Annual Growth Rate % | ||

| 1995 | 2015 | 1985–1995 | 2005–2015 | |

| Africa | ||||

| Lagos | 10,287 | 24,437 | 5.68 | 3.61 |

| Cairo | 9,656 | 14,494 | 2.28 | 1.97 |

| Asia | ||||

| Tokyo | 26,836 | 28,701 | 1.40 | 0.10 |

| Bombay | 15,093 | 27,373 | 4.22 | 2.55 |

| Shanghai | 15,082 | 23,382 | 1.96 | 1.85 |

| Jakarta | 11,500 | 21,170 | 4.35 | 2.34 |

| Karachi | 9,863 | 20,616 | 4.43 | 3.42 |

| Beijing | 12,362 | 19,423 | 2.33 | 1.89 |

| Dacca | 7,832 | 18,964 | 5.74 | 3.81 |

| Calcutta | 11,673 | 17,621 | 1.67 | 2.33 |

| Delhi | 9,882 | 17,553 | 3.80 | 2.58 |

| Tianjin | 10,687 | 16,998 | 2.73 | 1.91 |

| Metro Manila | 9,280 | 14,711 | 2.98 | 1.75 |

| Seoul | 11,641 | 13,139 | 1.98 | 0.32 |

| Istanbul | 9,316 | 12,345 | 3.68 | 1.45 |

| Lahore | 5,085 | 10,767 | 3.84 | 3.55 |

| Hyderabad | 5,343 | 10,663 | 5.17 | 2.83 |

| Osaka | 10,601 | 10,601 | 0.24 | - |

| Bangkok | 6,566 | 10,557 | 2.19 | 2.51 |

| Teheran | 6,830 | 10,211 | 1.62 | 2.30 |

| South America | ||||

| São Paulo | 16,417 | 20,783 | 2.01 | 0.88 |

| Mexico City | 15,643 | 18,786 | 0.8 | 0.83 |

| Buenos Aires | 10,990 | 12,376 | 0.68 | 0.50 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 9,888 | 11,554 | 0.77 | 0.84 |

| Lima | 7,452 | 10,562 | 3.30 | 1.32 |

| North America | ||||

| New York | 16,329 | 17,636 | 0.31 | 0.39 |

| Los Angeles | 12,410 | 14,274 | 1.72 | 0.46 |

Source: UNCHS (19966), pp. 451–456.

The great transforming force of the twenty-first century can already be seen: it is the informational revolution, uniting previously separate technologies – the computer, telecommunications, television – into a single medium for the generation, storage and exchange of information. Already, as this new economic revolution gathers pace, cities worldwide are increasingly networked in complex systems of global interaction and global interdependence, which produce a new international division of urban labour: the largest cities of the advanced world shed manufacturing and goods-handling in favour of advanced services; the largest cities of the newly-industrializing world take on these manufacturing functions; large cities in the barely-developed world, which are still only weakly connected to the global networks, subsist largely by informally exchanging basic services. In the networked world, we can distinguish a few global cities which provide the core nodes of this global exchange of information and control, and a larger group of perhaps forty or fifty aspirant cities – call them ‘sub-global’ – which compete with them and which provide global-level services in selected fields. Below these, but overlapping with them, are ‘regional cities’: large cities performing similar functions for small countries or for regional parts of larger countries. And below them, in turn, there is a host of what we can call ‘county towns’: medium-sized cities which act as service centres for their surrounding areas, but which may also provide some specialized services (such as health care or higher education or tourism) for national or international customers.

All of these masses of urban humanity thus have one common characteristic: they are cases of global networking, in which information and goods are exchanged over limited distances of a few hundred miles or kilometres, and in which a principle of local agglomeration holds true. Mega-cities show that even in the new world of cyberspace, the old economic principle of agglomeration still holds true: people still need face-to-face contact to do business, and so communication is easier and cheaper over shorter distances than over longer ones. And this is doubly true, because demand begets supply; thus the larger cities in these regions become major global air hubs and also the key points on the fast-emerging continental high-speed train systems.

By 2025, we can confidently predict that the whole world will be one urban network using automatic production, transportation and communication systems to free people to work in soft human services, in education, training, consultancy, community services plus an active citizenship – the ideal of all urban life since the Ancient Greeks. The great cities of the world, in particular, will be totally networked, forming a cyberspace version of the old Hanseatic League.

Thus, the twentieth century brought the urban transformation; the twenty-first century will transform the urban experience. The twentieth-century industrial and transportation revolutions freed millions of people from their lifelong bondage to the land – though too often, its first impact was to move them into equally degrading and exhausting forms of self-exploiting labour in the city. We can now see the real prospect for the coming century, which is that the informational revolution can potentially free them from this burden too.

But not inevitably or easily: indeed, one of the central questions, for the twenty-first century as for the one just ended, will be how we can consciously shape technological advance so that it liberates rather than exploits us. The experience of the twentieth century has been a very mixed one: in the cities of the developed world, millions have made better lives in more satisfying and less degrading work, but others have lost their work to machinery or to competitors in the developing world, where conditions all too often resemble those in London or New York a century ago.

The Urban Challenge

It is here, in the burgeoning cities of the developing world, that the real challenge lies. For there is a paradox: people are still coming into those cities, children are being born in those cities, because people believe that a better life lies in front of them. But in many cases these expectations are being cheated and may continue to be cheated. The disparities of income and wealth, both between cities and within cities, are not decreasing; they are increasing. The quality of the environment is not improving; in far too many cases, it is deteriorating. Crucial natural resources, vital to the future subsistence of these people, are not being conserved; on the contrary, despite solemn conference resolutions, they are actually disappearing.

An important word of warning: throughout this chapter and the rest of the book, we use the terms ‘developed cities’ (or ‘cities in the developed world’) and ‘developing cities’ (or ‘cities in the developing world’). This is a commonplace division, found in much of the development literature. But we fully recognize that today, increasingly, it represents a massive over-simplification. Cities in the ‘developed world’ show some characteristics of ‘developing cities’ (for instance, a substantial and increasing informal sector); even more importantly, many cities in middle-income ‘developing countries’ closely resemble their ‘developed’ counterparts in their economic and social and political structures – in particular, the presence of a significant modern economic sector, integrated into the global economy -and need to be distinguished carefully from other cities where the development process is still at an early stage and is still slow or fitful. And even at any given level of development, we also find significant differences – for instance in the relationship between the formal and informal sectors, or in kinds of housing and infrastructure provision – between different countries and continents; thus there is a Latin American model, an African model and more than one Asian model, all significantly different in important respects. Throughout the book, wherever necessary, we shall emphasize such important qualifications and distinctions.

However, such distinctions can easily lead us to lose sight of important generalizations; it is too easy to conclude that every city is significantly different from every other. So we think that the basic developed/developing distinction still has some value, especially in this broad opening overview. And we make no apology for the fact that our book concentrates heavily on the challenge presented by growth in the developing cities. Experience in the already-developed world may be relevant for these cities equally, it may be misleading. The point is to learn from best practice, wherever it can be found.

Forecasts of Urban Lives: 1900, 2000, 2025…

If we think about the lives of typical city people in the year 2000, how do we try to predict the equivalent lives of the year 2025, 2050, 2100? One way to start is to look at the century just gone. Observers in 1900 were daunted by the scale of the problems they found in the then-great-cities of the world. These cities were all in what we now term the advanced or developed world: London, Paris, Berlin, New York City. They had grown very rapidly, typically doubling their populations in the preceding half-century or even less. They had reached sizes never before recorded: six a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- The World Commission

- Chapter I. The Millennial Change

- Chapter II. Trends and Outcomes: The Urban World of 2025

- Chapter III. Two Scenarios: The Urban World of 2025

- Chapter IV. Rising to the Urban Challenge: Governance and Policy

- Chapter V. Good Governance in Practice: An Action Plan

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- References

- Index