![]()

INTRODUCING PUBLIC OPINION | 1 |

CHAPTERS

1 | The Meanings of Public Opinion

2 | The History of Public Opinion

3 | Methods for Studying Public Opinion

![]()

1

CHAPTER

The Meanings of Public Opinion

Public opinion is endlessly discussed in American politics and culture. The president, members of Congress, candidates for public office, interest group leaders, journalists, and corporate executives, as well as ordinary citizens, routinely ask: “What does the public think?” Political leaders need to know what sorts of policies and initiatives voters support, but other groups and individuals also need a working knowledge of public opinion. Interest group leaders must decide which battles to wage and how best to mobilize potential supporters. Journalists, who are key players in measuring and communicating public opinion, strive both to inform those of us who are curious about our fellow citizens’ attitudes and to understand what their audience wants. Corporate executives must pay attention to trends in American culture—what consumers think about, what they purchase, and generally, how they choose to live.

How can all these parties—and the rest of us—obtain information about American public opinion? There are many sources. Perhaps the most obvious indicator of public opinion is the sample survey or opinion poll. Quantitative data from surveys can often give us a sense of how Americans feel about policy issues, social practices, or lifestyle issues. The results of elections and referenda sometimes reveal citizens’ preferences in very dramatic ways; it is often said that an election is the only poll that matters. Yet students of American politics must go beyond these obvious techniques and consider all of the “places” that people’s opinions can be found: in the scripts of television programs; at political rallies, town meetings, or city council hearings; in the rhetoric of journalism; in the dialogue among friends who frequent a coffeehouse or neighborhood bar; in the political discussions one sees on the Internet and on social media or hears on talk radio. This book takes a broad view of what the phrase “public opinion” really means. To focus on survey results alone is to miss most of the story.

Three key terms summarize the concerns of this text: politics, communication, and social process. What do we mean by these words? Politics, in the context of this book, refers to the ways Americans govern ourselves and implement public policy. Our discussions of public opinion in politics go far beyond campaigns. Political campaigns do often attract close attention to—if not obsession with—every shift in the “horse race” for public support. The role of public opinion in policy debates receives less (although still considerable) media coverage, but may be even more important. Even politicians who claim not to care much about public opinion often watch closely for insight into how to present their policy proposals or which proposals are better not presented at all.

Although the connections between public opinion and politics are widely studied, communication issues have received far less scholarly attention than they deserve. How is public opinion expressed in America? How do the media influence the ways opinions are communicated and even the substance of those opinions? It is widely said that we live in an “information age,” but how have new communication technologies influenced public opinion? This book explores how both mass media and interpersonal forms of communication shape public sentiment. Since the diffusion of film in the early twentieth century, communication researchers have studied how mass media both reflect and shape people’s preferences and models of the political world. Social psychology provides insights into how a human tendency toward conformity often affects how people talk, behave, and vote.

Finally, public opinion is the result of social processes. That is, it is intertwined with various societal forces and institutions, such as the changing American demographic profile, the problems of inner cities, and the state of family life. Public opinion is embedded in culture and should always be considered in its social context.

WHY STUDY PUBLIC OPINION?

Public opinion research is a very broad field, because scholars in many disciplines need to understand how attitudes about public affairs are formed, communicated, and measured. As we will see in Chapter 2, public opinion study is as old as democracy itself: the ancient Greek philosophers believed that democratic institutions, to be effective, had to be grounded in a solid analysis of popular sentiments. Here we consider four broad reasons why so many scholars and public officials study and care about public opinion.

1. The Legitimacy and Stability of Governments Depends on Public Support

The US Declaration of Independence states that governments “deriv[e] their just powers from the consent of the governed.” That assertion implies that if citizens withdraw their consent, the government has no legitimate powers. “Democracy” may entail much more than public consent, but democratic theorists generally agree that it involves at least that much. Note that the declaration makes a claim about justice. Here, legitimacy is a normative concept—that is, an opinion (or a debate) about how things ought to be.

Normative issues aside, we might wonder: If citizens don’t support a government, is it likely to collapse? How public attitudes affect government stability is an empirical question, or a matter of fact. Perhaps widespread public dissatisfaction with government and lack of commitment to democratic values put democratic states at risk. Many observers believe that one or both of these factors helped Germany’s Nazi Party gain power in the 1930s and may explain the demise or fragility of democratic governments today. Others think that public opinion makes relatively little difference in whether democracies survive.

Public opinion researchers have investigated Americans’ attitudes toward government and political arrangements for many years. How much do members of the public trust their political leaders? Do they believe that Congress is responsive to their needs? Do they believe that political campaigns help them choose the best candidates? Do they yearn for a powerful leader who can “get things done,” essentially a dictator? Questions like these continue to inform—and at times to inflame—debates about legitimacy, stability, and other issues.

2. Public Opinion Constrains (or Should Constrain) Political Leaders

People’s opinions about policy issues, like their opinions about government and democratic values, engage both normative and empirical questions. Normatively, how should public opinion influence policy? Should governments do whatever citizens want them to do? Does the answer depend on the issue, or on exactly what citizens want? Empirically, how does public opinion influence policy? To what extent, and under what circumstances, does public opinion cause political leaders to do things they would not otherwise do or prevent them from doing what they want? What are people’s opinions about policy issues, anyway? Questions such as these inspire much research, debate, and armchair speculation.

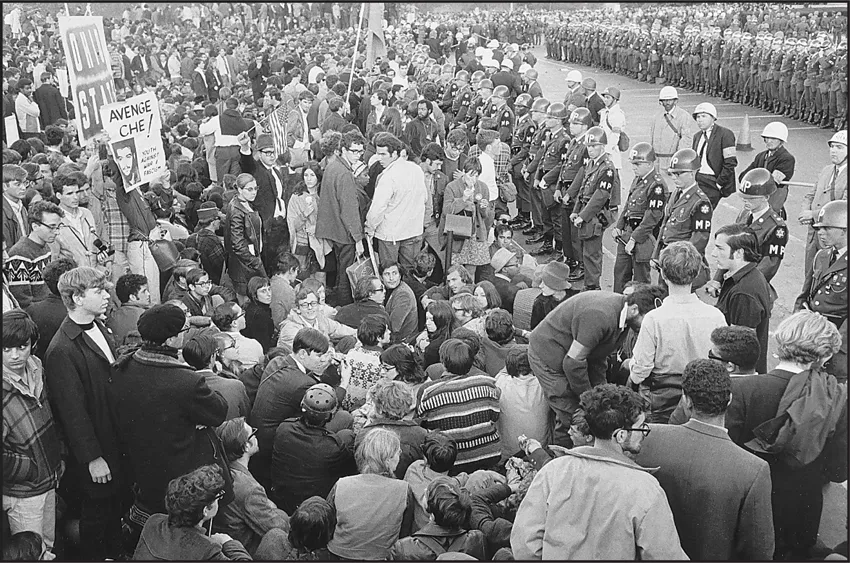

FIGURE 1.1 Public Opinion Demonstration during the Vietnam War Years.

SOURCE: Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Chapter 10 explores the links between public opinion and public policy in depth, and that linkage is among the most important reasons we study popular attitudes. Presidents, members of Congress, state legislators, and even local city council members must always be aware of public opinion. Sometimes leaders promote a policy and the public quickly supports their ideas, such as when the public “rallies around the flag” in the early days of a military conflict. At other times a groundswell of public opinion comes first, and leaders respond with action (see Figure 1.1). For the most part, however, the interaction between leaders and the public is far more complex, because communication is so imperfect. Journalists, for example, can knowingly or unknowingly distort public opinion; policymakers can confuse the “voice of the people” with the voices of media professionals. Or journalists may affect public opinion by misrepresenting or ignoring aspects of a policy debate.

3. Public Opinion Provides Clues about Culture

Public opinion on policy and social issues can offer crucial insights into larger currents in American culture. Since it is difficult for social scientists to study the many dimensions of American culture, we often draw inferences about that larger culture from narrower studies of public attitudes.

For example, researchers have researched public attitudes about welfare programs to study broader cultural attitudes. Since the 1960s, when the US government initiated several large antipoverty programs, public opinion researchers have asked Americans how they feel about such programs. The results of these studies tell us a lot about American norms and values. (Of course, varying descriptions of the programs can elicit very different answers—and those differences can contribute to our knowledge.) If, over the course of several years, survey respondents increasingly support the idea that welfare recipients should be required to work, we learn something about changing values: the trend may indicate a growing impatience with the poor, a renewal of the work ethic, or a general resurgence of conservative political ideology. All of these hypotheses need more rigorous study, but social scientists are often “tipped off” about larger cultural trends by survey results or other evidence about public opinion.

One might argue that public opinion and culture are so intertwined as to be inseparable. In addition to being the source of aesthetic “products” (e.g., art, music, dance, and the like), culture is a sum of people’s norms, values, and sentiments—common subjects of public opinion research (see Box 1.1). In this text we do not assume that any part of popular culture is inherently outside the bounds of public opinion, but neither do we argue that public opinion subsumes everything worth knowing about culture.

4. Political Leaders Seek to Change or Mobilize Public Opinion

While political leaders may be constrained by public opinion, they also try to influence it. The most obvious circumstance is wartime, when presidents typically urge citizens to make large sacrifices: to send their sons and daughters off to war, to conserve scarce resources, and to contribute in other ways. During World War II this sort of mobilization was not particularly difficult. That war was widely perceived as, to use Studs Terkel’s phrase, a “good war,” in which we were fighting for freedom for ourselves and others. Other mobilizations for war have been more difficult or more complicated. A vocal and intelligent antiwar sentiment existed in the days before our entry into World War I, for example, as a variety of writers and artists attempted to persuade Americans that the United States should stay out of European affairs (see Figure 1.2). And in the 1960s President Lyndon B. Johnson attempted to convince an increasingly resistant public that US military action in Vietnam was proper and morally sound. Often, of course, political leaders do not agree about what should happen, and then they may engage in a struggle to win public opinion over to their respective sides.

BOX 1.1

Culture, Art, and Public Opinion

History often provides excellent examples of how culture and public opinion are interwoven. Let us take one interesting historical case of this relationship—the popularity of Shakespearean drama in nineteenth-century America—to illustrate that nexus. Our example comes from historian Lawrence Levine’s Highbrow, Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America. Today Shakespeare is generally considered “highbrow” entertainment with limited appeal, but in the nineteenth century his plays were vastly popular across class lines.

Levine argues that Shakespeare’s drama was so popular because it appealed to some basic beliefs among Americans at the time. In particular, Shakespearean drama emphasized the struggle of the individual: “His plays had meaning to a nation that placed the individual at the center of the universe and personalized the large questions of the day.”1

Levine gives an example of how popular political feeling of the period manifested itself in May 1849, when two leading Shakespearean actors (the American Edwin Forrest and the British star William Charles Macready) were giving competing performances in two different New York theaters:

Forrest’s vigorous acting style, his militant love of his country, his outspoken belief in its citizenry, and his frequent articulation of the possibilities of self-improvement and social mobility endeared him to the American people, while Macready’s cerebral acting style, his aristocratic demeanor, and his identification with the wealthy gentry made him appear Forrest’s diametric opposite. On May 7, Macready and Forrest appeared against one another in separate productions of Macbeth. Forrest’s performance, at the Broadway Theater, was a triumph both dramatically and politically. When Forrest spoke Macbeth’s lines, “What rhubarb, senna or what purgative drug will scour these English hence?” the entire audience, according to the actor Lester Wallack, “rose and cheered for many minutes.” Macready’s performance, at the Astor Place Opera House, was never heard—he was silenced by a storm of boos and cries of “Three groans for the codfish aristocracy,” which drowned out appeals for order from those in the boxes, and by an avalanche of eggs, apples, potatoes, lemons, and ultimately, chairs hurled from the gallery, which forced him to leave the stage in the third act.2

The next evening 1,800 people gathered at the Opera House to shout Macready down. A riot ensued, and when it was over, 22 people were dead and more than 150 injured.

For our purposes, this colorful yet tragic incident in American theatrical history has a variety of implications. To begin with, it demonstrates how the performing arts rest on ideology: Americans of the mid-nineteenth century, as well as those living in the early twenty-first century, have often been hostile toward art and artists who somehow reflect unpopular beliefs. This example also underscores the fact that public opinion and culture are inextric...