![]()

1

Introduction

In some important respects, American political history has been characterized by a gradual but unmistakable march in the direction of more inclusiveness and more democracy It took nearly two hundred years, but the franchise was extended beyond propertied males to all white males in the nineteenth century, then to women in the early twentieth century, then to African Americans in the South in the 1960s, and finally to young people aged eighteen to twenty years in 1971. Opportunities for power for the previously disenfranchised and powerless have flowed from that.1 In addition, the representative institutions of government in the United States, as well as the political parties, have opened up their decisionmaking processes in ways that distinguish American democracy from every other democracy in the world.

This seemingly inexorable movement in the direction of more democracy has never reached what some regard as its logical conclusion—a political process in which the people directly rule themselves—because of the impracticality of direct democracy in a huge sprawling country with many millions of people. Now, however, computers, the Internet, and interactive television can change all that.

Great advances in communications technology have always had profound effects on American politics. In the 1920s, the advent of radio forever changed the relationship between the president and the people. Calvin Coolidge was the first to use the new mode of communication to his personal political advantage, and shortly thereafter Franklin Roosevelt refined the technique with his legendary Depression Era "fireside chats."2 A few decades later, television further changed how public officials and candidates interacted with the public. The political parties are still reeling from its impact, particularly the ability it has afforded candidates for office to connect directly to voters without the mediation of party leaders.3

The twenty-first century promises change of an even more thoroughgoing nature. At the very least, advanced technologies will give citizens more avenues for contacting and petitioning elected officials. In addition, computer technology may be used to make it easier to put more initiatives on the ballot in the states, perhaps one day even in federal elections. It is likely that the Internet and interactive television will affect our politics in other ways—perhaps one day every citizen will be plugged into government at the state, local, and federal level. But will advanced technologies be used in imaginative ways to enhance dialogue and democratic deliberation involving more citizens, or will they be used primarily to promote "instant democracy"—essentially, more frequent plebiscites conducted by computer on the issues of the day? Most political scientists and scholars of American politics think that the trends point in the latter direction.

What are we to make of the potential for dramatic change in the way ordinary citizens interact with, or perhaps replace, elected officials? What effect might these changes have on the American constitutional system? Does the increased reliance on direct and participatory forms of democracy constitute progress? This is the time to take a step back and consider the implications of some of these developments, both those that have already taken place and those that may in the future. In this book we will look at the spread of direct democracy in the United States and the ideas that fuel its spread, speculate as to the direction citizen involvement in policy-making is likely to take, and consider the wisdom of plebiscitary democracy in light of recent scholarship and experience.

This chapter begins with an overview of one of the main issues confronting American democracy at this time: a public that may be more alienated from the political process than it has ever been. Most observers agree that there is something seriously wrong with democracy in America; certainly the public seems to have lost faith in the political system. There is, however, no consensus as to the cause. Informed observers offer sometimes diametrically opposed explanations. Some say we have too much democracy and too much direct access to elected officials who are not given the leeway to make carefully considered and responsible public policy. These critics suggest that politicians are excessively responsive to public opinion when making policy. Others claim that there is too little democracy. Politicians are insulated from real people and out of touch. The United States' political institutions need to be opened up and made more accessible. These observers say that citizens should be able to take policy-making into their own hands; perhaps we should even remove the impediments—including the constitutional checks and balances—that stand in the way of the realization of a purer democracy.

In the second part of the chapter, I present the argument of this book. My aim is to counter and refute the argument made by advocates of more direct democracy, which is this: Representative institutions act to stymie the expression of the popular will and fail accurately to consider the public interest when policy is made. The solution, according to advocates of direct democracy, is simple: allow the direct expression of the popular will by permitting citizens to vote to determine public policy. There are two problems with this solution. The "popular will" cannot be identified with any precision or certainty by taking a vote, a point shown conclusively by a relatively new field of inquiry in the social sciences. In addition, the very idea that the results of a plebiscite should be implemented into public policy is potentially dangerous and illiberal. I argue that in light of our new technological capabilities, constitutional limits on direct democracy actually are now more important than ever before—precisely because of our rough-and-ready populist traditions, precisely because direct democracy is so incredibly seductive in the American cultural context.

The Crisis of Faith in the Political System

Commentators and specialists on American politics from across the ideological spectrum may not agree on much, but they do tend to agree that there is something wrong with the state of democracy in the United States. There is ample evidence that the general public concurs. Polls regularly indicate that large majorities think that the country is "on the wrong track," even now when the economy is going great guns. The public's attitude toward the Congress and the political process in general is one of bitter disdain, an attitude that has proved to be quite stable over the last twenty-five to thirty years.4 By overwhelming majorities, Americans believe that the country is run by a few big interests and not for the benefit of the people.5 Even the popular second-term president Bill Clinton is not trusted and was thought not "honest enough" to be president by 52 percent of the public before he was impeached for perjury and obstruction of justice, according to a September 1997 Time magazine poll.

The most obvious manifestation of Americans' disaffection with politics as usual is that we don't even bother to vote. The trend has been generally downward since 1960. Turnout fell below 50 percent for the 1996 presidential election and was at an abysmal 36 percent in the 1998 off-year congressional elections. This trend is all the more remarkable considering that the population is considerably older, better educated, and richer than it was in 1960—factors that supposedly correlate with a higher likelihood of voting—and many barriers to voting have fallen in the last thirty-five years, such as poll taxes, discriminatory registration tests, and numerous stringent residency requirements.

In a country that is at peace and far wealthier than ever, the government seems hamstrung by the combination of a fiscal deficit (even in surplus we are for the most part living off the revenue from payroll taxes, and the impending retirement of the baby boom generation is likely to lead to a return to large deficits) and a confidence deficit. The vast majority of the people do not trust their government and are unwilling to support a significant national commitment of resources to any of the problems currently plaguing us.6 Politicians are loath to introduce ambitious legislation of the sort commonplace in the 1960s. An activist Democratic president who idolized John Kennedy and ran the George McGovern for President operation in Texas in 1972 and who proposed a comprehensive overhaul of the entire health-care system in his first term now proudly announces that "the era of big government is over."

Compare that with the robust attitude of the public in 1960, when a much less wealthy country in the midst of an expensive standoff with the Soviet Union all around the globe, and even in outer space, was supremely confident in the government's ability to conquer social problems.7 Today, Americans of all stripes are better off than their parents and enjoy far more benefits from the government in the form of numerous and sometimes lavish subsidies and tax breaks;8 at the same time we have no confidence in that government, are more sure that it is corrupt, and are gloomier about the prospects for our children. No wonder that the preeminent political book of the early 1990s, by E. J. Dionne, a columnist at the Washington Post, was Why Americans Hate Politics.9

Commentators and ordinary citizens alike are disturbed by many particular aspects of the political system. Most prominent among these aspects is the influence of special interests in the government, particularly the Congress. In addition, the government is thought to be corrupt, out of touch, spendthrift, and unable to deal with the most pressing issues of the day: crime, environmental degradation, health care, education, the approaching insolvency of Social Security, the increasingly unequal distribution of wealth, chronic poverty, and moral breakdown.

Most important, the public thinks the problem is systemic. Politicians themselves chime in. Retirements from Congress have been occurring at accelerating and sometimes record-breaking rates in recent years, often including the most vital, active, and respected members. Democrats and Republicans alike, such as recently retired Senators Bill Bradley (D-New Jersey), John Danforth (R-Missouri), Tim Wirth (D-Colorado), Sam Nunn (D-Georgia), Alan Simpson (R-Wyoming), and Hank Brown (R-Colorado), describe the stalemate, ineffectiveness, and futility of recent Congresses. The conventional wisdom is that there is something wrong with the system, the way our government goes about its business.

Too Little Democracy? Or Too Much?

Though commentators of different ideological persuasions agree that there is a systemic problem, they disagree, sometimes vehemently, as to the underlying cause of the troubles in our political system. Most prominent observers of American politics tend to fall into one of two camps. One group believes that there is too little democracy in the United States. These "populists" say that politicians are out of touch, are insulated from regular people, and serve only the monied interests that can afford to lobby them. Our constitutional system, populists say, with its checks and balances, separate branches of government, and a tradition of federalism which tends to weaken and decentralize the political parties all feed into the problem of a government too distant from and unresponsive to the concerns of the people.

These critics say that the solution to the problems that confront American democracy is more democracy—programmatic political parties, more direct input, more referenda, more initiatives, more citizen-based action. Observers as various as the venerable scholar of American government James Sundquist and the conservative gadfly and author Kevin Phillips have advocated at least a streamlining, if not a rethinking, of the basic structure and workings of the American constitutional system.10 The political theorist Benjamin Barber calls for more community-based action and active citizenship to correct the ills of a system hampered in its functioning by a too-distant elitist political establishment.11 Barber and Phillips, along with a decisive majority of the public,12 support the use of a national referendum to override or bypass the Congress. Scholars such as James Fishkin and Robert Dahl have proposed statistically representative citizen assemblies to provide policy advice to elected officials.13 They view this innovation as a corrective to the antidemocratic lack of diversity and the isolation of the political class. Many of these critics view the American system of separated institutions, multilayered checks and balances, and weak decentralized parties as antiquated and fundamentally undemocratic—as roadblocks to the establishment of a more vital and democratic political system.

On the other side are those who claim that the mismanagement of public affairs and the general dissatisfaction with the political system are due to an excess of democracy. Twenty-five years ago the political scientist David Mayhew, in his classic essay Congress: The Electoral Connection, depicted the Congress as a hyper-responsive body geared to the reelection-seeking goals of the members.14 According to Mayhew, members of the House and Senate had brilliantly structured the institution both to serve the parochial needs of their constituents and to address larger problems in ways that constituents would find desirable—although in ways that did not necessarily confront these problems in a serious way The committee system, the party organizations, and the members' offices were all organized to serve the particular interests of the members' constituents to ensure reelection. Congressmen might pontificate endlessly on the floor about Vietnam or forced busing or taxes with no apparent effect, said Mayhew, but when it came to serving the immediate needs of their constituents, the Congress as an institution operated with breathtaking efficiency. The journalist Steven Stark found things substantially the same in the 199015

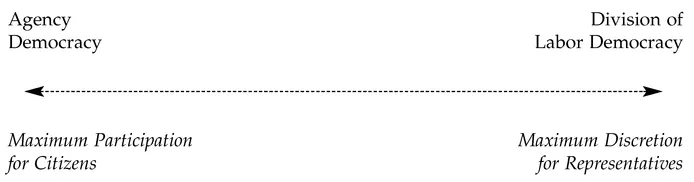

FIGURE 1.1 King's Conception of Representative Government

Contemporary observers such as the political scientist Anthony King and the journalist Jonathan Rauch find a government both excessively responsive to the people's immediate needs and one lobbied effectively really hectored, by ordinary people.16 Rauch stresses that it is "we the people"—yes, the ordinary people—who are the problem. In some respects, Rauch says, the term "special interests" is a misnomer, since many of the special interests lobby for ordinary people by protecting and expanding broad-based entitlement programs. In fact, most Americans are members of some association or interest group that is active in the Washington power game.

It is worthwhile to explore King's thesis as propounded in his recent well-received book, Running Scared, more carefully. He begins by developing a slight modification of the old "delegate-trustee" formulation of legislative representation. His conception of democracy is a continuum from "agency" to "division of labor" (see Figure 1.1). In the agency conception, politicians act as agents of the public, carrying out their immediate wishes to the best of their ability to discern them. And the public views its role as an active one, looking over the shoulder of its "agents" as they go about their business. In the division-of-labor conception, politicians are given the space to make decisions without being subjected to constant public scrutiny. In this conception, the public weighs in on Election Day to evaluate the work of the politicians.

According to King, democracy in the United States resembles the agency conception more than in any other country in the world with the exception of Switzerland. As he points out in describing the allure of agency democracy and the drift in the direction of a fully "plugged in" plebiscitary style of democracy:

Representative government of the kind common throughout the democratic world can be only a second-best. The ideal system would be one in which there were no politicians or middlemen of any kind but in which the people governed themselves directly; the political system would take the form of more or less continuous town meetings or referendums, perhaps conducted by means of interactive television.17

King goes on to point out that the people in a country with an agency political culture will be constantly frustrated. They will never be satisfied with their politicians in such an environment, he says, since a purely agency form of democracy is impracticable.

This agency political culture is part and parcel of the populist tradition in the United States. Populism connotes a mistrust of the elite along with an abiding faith in the wisdom of ordinary people and their right to govern themselves by majority rule. It has always been a central part of American political culture.18 The United States is unique as a nation that is founded on democratic ideals as variously expressed in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitu...