![]()

1

Becoming Alice Paul

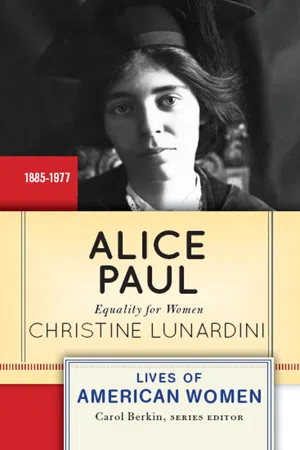

Alice Paul, the oldest child of William and Tacie Paul, was born in 1885. The struggle for women’s rights, begun in 1848, had expanded over the years but could count only a handful of suffrage states where women were allowed to vote. No one, least of all Alice’s parents, could foresee that this tiny addition to the American population was destined to change all of that.

William Mickle Paul married Tacie Haines Parry in 1881. He was just thirty years old but already a successful businessman and community leader in what is now Moorestown, New Jersey. A cofounder and the president of the Burlington County Trust Company, Paul sat on the Board of Directors of several area companies and invested in real estate. Both he and his new wife were descended from illustrious and influential colonial leaders. William could claim no less than John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Winthrop’s vision of Massachusetts as the “city on a hill,” which would shine as a beacon for all to follow, helped shape the character of the New World colonies. Another of William Paul’s ancestors had been jailed in England because of his Quaker religious beliefs. After his release he, too, made his way to the New World, the first Paul to do so, and settled in New Jersey. The community, originally named Paulsboro and later renamed Moorestown, was located in Burlington County, bordering Pennsylvania, less than ten miles from Philadelphia. By the time William was born in 1850, Burlington County had become home to a thriving Quaker community. It is likely that William attended the same Friends School in Cinnaminson, New Jersey, as his future wife.

Tacie Parry Paul, born in Cinnaminson, could, like William, trace her ancestors back to the earliest colonial settlers. On her side of the family, her lineage went all the way back to William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania Colony. After graduating from the Cinnaminson Friends School, Tacie was one of the first women to attend Swarthmore College. Her father, Judge William Parry, cofounded Swarthmore, along with, among others, Lucretia Mott, one of the most influential abolitionists in the years leading up to the Civil War and a longtime women’s rights advocate. Judge Parry raised much of the funding for the school. Tacie would have been one of the first women graduates of Swarthmore had she not left during her final year to marry William Paul. At that time, married women were not allowed to attend school. Perhaps to lessen her father’s disappointment, Tacie promised that all of her children would spend at least a year at Swarthmore in order to benefit from a Quaker education.

William and Tacie subscribed wholeheartedly to gender equality, separation from materialistic society, a close relationship with nature, and working toward a better society. In accordance with a Quaker tenet, all members of the community were urged to find their “inner light”—namely, the motivation to act on their conscience and to influence the creation of a “better society” as they personally defined it. The broad strokes of a better society included beliefs in pacifism, nonviolent resolution of problems, equal justice, and personal growth. Two years after they were married, the Pauls purchased a sprawling working farm in Mt. Laurel, New Jersey, a few miles from Moorestown, which they promptly named Paulsdale Farm. The 170-plus-acre farm, complete with a large rambling farmhouse, was another measure of William’s business success. From its enormous wraparound veranda, one could look out on a sweeping front yard, several barns and other buildings, and fields of various crops and animals. Although William considered himself a gentleman farmer, his hired hands did most of the actual farm work. The family also employed several Irish maids to help with the work in the main house. It was in this prosperous and peaceful setting that the Pauls’ four children were born.

Alice Stokes Paul, named for her maternal grandmother, arrived on January 11, 1885. Her three younger siblings followed in fairly rapid succession: William (1886), Helen (1889), and Parry (1895). Growing up at Paulsdale Farm became a life lesson in the core beliefs of the elder Pauls. Though removed from the surrounding community, the farm was certainly not isolated. Relying on its bounty kept the Paul children close to nature, while their various chores taught them the virtues of perseverance and industry. The children enjoyed competitive games, but, in keeping with Quaker belief, music and dancing were not part of their young lives. They were very aware that their Irish maids went off to dances in town. As Alice noted years later, they assumed that only “a sort of common people” engaged in that kind of activity.1 It is likely that William Paul was the more conservative parent when it came to music and dance. Shortly after his death, when Alice had already left for college, Tacie Paul purchased a harpsichord for the family home so her daughter Helen could take music lessons.

Alice also remembered at a very young age going with her mother to woman suffrage meetings at neighbors’ homes. Since all of their relatives and friends were Quakers, she grew up accepting women’s equality as a given and not as something up for debate. More than anything else, however, Alice loved to read. She loved the classics. If she was off on her own, more than likely she could be found at the local Friends Library. She recalls reading every line written by Charles Dickens “over and over and over again.”2 These early experiences were already beginning to reveal Paul’s complex nature. On the one hand, she clearly believed the household staffs were commoners with lower social standings than the Pauls. On the other hand, she believed without question in equality for women and found great resonance in the social issues that Dickens wrote about, including the relationship between class and poverty.

Because her parents believed deeply in gender equality, they expected Alice to lead her younger siblings by example. Alice easily adapted to this position of responsibility. She strove to shine in her parents’ eyes—and succeeded in doing so. Her father had ultimate confidence in his oldest daughter’s ability to do whatever was asked of her. He observed more than once that “whenever there is anything hard and disagreeable to do, I bank on Alice.”3 And her mother’s words of advice, which were repeated each time Alice was asked to take on a new task, stayed with her throughout her lifetime: “When you put your hand to the plow, you can’t put it down until you get to the end of the row.”4 Her parents’ teachings and her Quaker upbringing—combined with the worldviews of the many authors, such as Dickens, whose words she internalized—were strong influences in shaping her own worldview. They also helped to teach her how one should live life.

All four of the Paul children attended the Moorestown Friends School. And, in keeping with Tacie Paul’s promise to her father, all four attended Swarthmore for at least one year. The younger Paul children, however, chose to transfer to different colleges after their year was up. Only Alice stayed at Swarthmore. She loved college life. She thrived on being a part of the intellectual community of teachers and fellow students that she found there. She also liked the atmosphere steeped in Quaker tradition. Her intelligence and thirst for knowledge ensured that she would do extremely well at Swarthmore. That fact may explain her siblings’ preference for educational experiences elsewhere—an alternative preferable to having to live up to Alice’s reputation!

After graduating at the top of her class from the Moorestown Friends School in 1901, Alice was more than ready for college. She did not yet have a clear idea of the path she would follow. She did know that, as soon as she enrolled at Swarthmore, she would have to declare her major. Most of the other women students were taking majors in subjects like English literature and Latin. Because she was so well-read and had done so well in these areas at the Friends School, Paul was determined to take the path less followed. She knew absolutely nothing about science or math. To her, the logical choice was to spend her time at Swarthmore learning about what she didn’t know rather than concentrating on academic pursuits that were in her comfort zone. She chose biology as her major because, as she readily admitted, “this is the only way I will ever learn about [science].”5 Her choice of a major in science revealed another of Paul’s characteristics: the sense that there was little to be gained from redoing something already done. To be clear, pursuing a career in science had never really entered Paul’s mind. Although she thought she should know as much as she could about science and higher mathematics, these subjects just didn’t interest her as a career choice.

A few months into her freshman year at Swarthmore, Paul suffered a personal tragedy, probably the first in her young life. In the winter of 1901, her parents took a vacation trip to Florida. They stayed only two weeks and then quickly returned to New Jersey; as Paul would subsequently recall, her father’s business activities kept him extremely busy. Soon after their return, Mr. Paul caught a cold that quickly became a very bad cold and then turned into pneumonia. In the blink of an eye he was gone, succumbing to the pneumonia and leaving Mrs. Paul with four young children. Alice had just turned sixteen. When asked many years later how she dealt with her father’s death, Alice’s response was vague at best: “I just remember that life went on.”6 For someone to have so vague a recollection about a seminal life event may seem odd at first glance. In fact, her response reflected another Paul characteristic. She consistently downplayed or was extremely vague about events in her life that, factually, had to have affected her deeply. Whether it was the death of her father or being force-fed as a suffrage prisoner or being committed to a psychiatric ward by the government because of her picketing activity, Paul’s personal recollections of these events were often sketchy, if not dismissive. Were it not for the testimony of others who worked with her and ample printed coverage of her experiences, she might still be regarded historically as little more than a misguided eccentric. As late as the 1970s, many historians of the woman suffrage movement viewed her as marginal at best and counterproductive at worst.

Yet life did go on for Alice, and Swarthmore continued to suit her. At that time, the college enrolled about four hundred students. In keeping with Quaker beliefs, about half the students were women—a ratio that made Swarthmore stand out among coeducational schools of the day. Alice enjoyed participating in sports; she excelled at tennis, loved basketball, and played field hockey as well. A lifelong friend whom she met at Swarthmore, Mabel Vernon, remembered Alice as rather shy but very sports-oriented. In those days, Vernon noted, Alice was the picture of health. Despite her shyness, Alice enjoyed conspiring with her close friends to play pranks on fellow students. One night, she and her friends tied together several white sheets and hung them out the dorm window, hoping to shock passersby when they spotted the ghostly apparitions. In many ways, this early version of Alice Paul was the typical college coed of her day, stretching the boundaries of her experience and enjoying the camaraderie of her friends.

For the first time in her memory, Paul experienced music and dance, both of which she seemed to enjoy. For Quakers, consensus on all things was not as important as interpreting one’s inner light. Those making the decisions at Swarthmore were comfortable with exposing their students to music and dance. Swarthmore students were encouraged to play musical instruments, and on Sunday evenings everyone could sing or listen to hymns performed by members of the community. Alice took dance classes and attended the college-sponsored dances for female students, the custom at Swarthmore. There were also weekly gatherings to which all students were invited. It was an opportunity to socialize, to chat with and get to know other students. Alice was also content to spend long hours reading and taking walks alone or with classmates along the Crum, a stream that bordered the Swarthmore campus.

Swarthmore students were expected to attend Quaker services each week and to take all their meals together as well. Students were assigned designated tables and seats when they arrived on campus. For four years they ate all their meals with the same group. Each table was presided over by a college dean, charged with instilling in her pupils proper etiquette as preparation for taking their place in polite society. Everyone said grace together, and then the male students would go out to the kitchen and bring in the food for the table. The dean signaled the end of each meal when “with great ceremony she rose and walked out and with great ceremony the students rose and walked out behind her. It was a very dignified and a very lovely regime.”7

In her sophomore year Alice joined a debate society, probably because she did not think her public speaking skills were at all impressive. Debating would be an opportunity to improve upon them. Mabel Vernon first met Alice Paul when both were competing in an extemporaneous speaking contest at Swarthmore. Knowing her friend to be a gifted speaker, Paul sought out her advice. Paul had no doubt that Vernon would win the competition. She confided to Vernon that she (Paul) would almost certainly be eliminated. She had very little confidence in her own public speaking ability. Vernon offered what advice she could to the uncertain Paul. In the end, Vernon did win first prize in the event but Paul also made the finals, indicating that she was a much better speaker than she gave herself credit for. Much later Vernon observed that this incident, too, had been characteristic of Alice Paul: she always seemed to downplay her own talents and abilities and believed that others could do things so much better than she.

Paul continued to do well at Swarthmore. However, until her senior year she had no clear idea of her goals for the future. She maintained an excellent academic standing in her biology major, though she still had no real passion for the subject. She had begun to think about teaching after Swarthmore. For women students who wanted to support themselves after college, teaching was the most common goal. Most students did not think in terms of working toward a career or even supporting themselves. The vast majority of students planned on returning home after college. For women students, this meant living with their families until they were married—if they married. For male students, it was usually a matter of going into business with their fathers, whether that meant some form of commerce, farming, or perhaps a profession such as law or medicine. Alice herself might well have graduated with no better idea of where her interests lay were it not for Swarthmore’s newest faculty member, Professor of Politics and Economics Robert Clarkson Brooks.

In her senior year Alice took Brooks’s courses in political science and economics. For the first time in her college career, she had found something that excited her greatly. Brooks taught his students that the relationship between economy and politics could determine the kind of social changes that would result in a better society. He also explained that political activism did not require holding public office. This gave the Swarthmore coeds something to ponder, as very few women held any kind of public office at the time. A firm advocate of “progressivism,” a movement just beginning to effect change across the country, Brooks offered his students the prospect of the better life so integral to Quaker beliefs. This new way of looking at social problems and how to solve them excited Paul immensely. It didn’t immediately resolve her indecisiveness about her future, but it did cast a new light on that future.

Paul graduated in 1905. In recognition of accomplishment in an area other than science, she was named the Ivy Poet of her class. The honor required that Paul write an original poem that she would then recite at a Swarthmore traditional ceremony. Each graduating class placed a brick in an edifice constructed for that purpose to commemorate their years at the school. Being named the Ivy Poet terrified Paul for two reasons. First, she had never written a poem before and she didn’t think she possessed the proper creativity to pull it off. Second, despite her public speaking efforts, she didn’t believe that she could recite the poem in front of the entire college community. She turned once again to Mabel Vernon, requesting that Mabel coach her so that she could get through the ordeal without embarrassing herself, her class, or the college. In the end, her first and only poem turned out to be much better than she thought she was capable of. She also did a very creditable job of reciting it at the ceremony.

Graduation brought another entirely unexpected opportunity. Although Paul had no way of knowing it, taking Professor Brooks’s classes gradually but thoroughly changed the direction her life would take. She did so well in his classes that Brooks nominated her for a postgraduate scholarship awarded by the College Settlement Association (CSA). The college settlement movement started by Jane Addams had become very popular by that time. Addams and Ellen Gates Starr founded Hull House in Chicago in 1889. They intended to provide the tools that would allow immigrant populations to assimilate into American life. Their classes, which were taught in English and exposed immigrants to American art and culture as well as to more practical instruction in the labor market and citizenship, brought throngs of would-be Americans to Hull House. Very quickly, Hull House also became a place where social issues were addressed, including education, child labor, occupational and workplace safety, and wages and hours. Before long, Hull House had become the best example of what settlement houses could be. More than five hundred settlement houses were opened across the country, many of them modeled after Hull House. When Paul graduated from Swarthmore, the CSA awarded one-year scholarships to graduates of select colleges who seemed most suited for the field of social work. Paul had never considered social work as a career. She accepted the scholarship as a means of exploring that avenue further. Given the choice of which settlement-house city she wanted to go to, Paul chose New York.

Paul arrived in New York in the fall of 1905. She was assigned to the Rivington Street Settlement House and enrolled in the New York School of Philanthropy, also part of the scholarship award. Founded in 1898, the School of Philanthropy was established to provide a level of professionalism for social workers. It later merged with Columbia University and became the Columbia University School of Social Work. Before social work developed into an academic discipline, charitable giving tended to be haphazard at best. A system in which the needs of clients could be easily matched with organizational outreach programs just did not exist. Indeed, there was no structure even for determining or verifying a client’s needs. The founder of the School of Philanthropy was a much-respected figure in charity organization circles. As the first president of the school, he was instrumental in developing much more rigorous training for his students. As a student, Paul attended lectures and went on numerous site visits to various institutions.

In addition to her academic work at the School of Philanthropy, Paul became a Rivington Street associate case worker. Rivington Street was located in a largely Jewish and Italian neighborhood, and Paul’s scholarship provided for room and board at the settlement house. She spent her year there working with experienced social workers, mostly observing. They visited several families on an individual basis, and Paul—as the assistant to the case worker—wrote supplemental reports on their status, along with whatever recommendations she believed were in order. In short, it was in-depth training in preparation for becoming a case worker.

Paul graduated in 1906 with a postgraduate degree in social work. Although she worked diligently throughout the year to fulfill the commitment she had made by accepting the scholarship, the most noteworthy aspect of her experience was her attitude toward social work. “I could see that social workers were not doing much good in the world. That’s what I thought, anyway.” Nearly seven decades later, her opinion had not changed. “I still think so. So to spend all your time doing something that—you knew you couldn’t change the situation by social work.” Her attitude toward social work may have been influenced by the newness of the discipline. She never committed to being a social worker. And, “[b]y the time I had been there awhile, I k...