- 287 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Do we read character in faces? What information do faces actually provide? What are the social and psychological consequences of reading character in faces? Zebrowitz unmasks the face and provides the first systematic, scientific account of our tendency to judge people by their appearance. Offering an in-depth discussion of two appearance qualities that influence our impressions of others—"baby-faceness" and "attractiveness"—and an analysis of these impressions, Zebrowitz has written an accessible and valuable book for professionals and general readers alike.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Judging a Book by Its Cover

Afterwards on becoming very intimate with [the Captain], I heard that I had run a very narrow risk of being rejected on account of the shape of my nose! [He] was convinced that he could judge of a mans character by the outline of his features, and he doubted whether anyone with my nose could possess sufficient energy and determination for the voyage.1

The foregoing passage from Charles Darwin’s autobiography reveals that the theory of evolution was almost lost for want of a proper nose: Darwin’s nose practically cost him passage on the HMS Beagle, the ship from which he made many of the observations that spawned evolutionary theory Darwin’s anecdote illustrates the tendency to “judge a book by its cover,” and the captain of the Beagle is by no means unique in this respect. After we had become best friends, my college roommate confessed her first impression of me. Jayne had perceived me to be the kind of person who would happily comply with all of her wishes. She expected to have the last word in decisions such as how to arrange the furniture in our room, when to have quiet times for study, and when to have “lights out.” She even anticipated that I would be her “gofer”: running to the candy machine to bring her a Clark bar or trudging to the laundry room to move the clothes from the washer to the dryer.

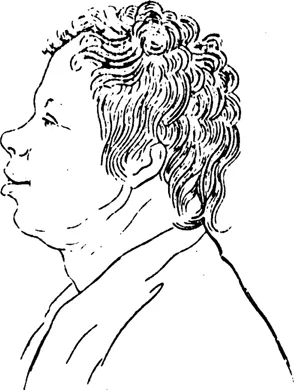

Although we may scoff at the judgments of the captain of the HMS Beagle, and I certainly laughed with Jayne about her erroneous first impression of me, one can’t help but wonder where such impressions come from. We subscribe to maxims such as “don’t judge a book by its cover” and “pretty is as pretty does,” but the fact is that our views of other people are strongly influenced by superficial qualities, particularly their facial features. An honest appraisal of your reactions to the people you meet will surely reveal instances in which you had the immediate perception that someone was a “nice guy” or, to the contrary, that he was not to be trusted. You may or may not have wondered how you came to this conclusion. Was it something in his tone of voice? In his behavior? In his face? Although it may have been any one of these things, his face would have been sufficient. Consider the man in Figure 1.1. My tongue-in-cheek observation that he looks highly intelligent has elicited the same chuckles from U.S. and Korean audiences. The fact is that he looks quite simpleminded to all observers. Why is that so? This is one of the questions that will be addressed by this book.

Figure 1.1 Fool in Profile. J. C. Lavater (1879). Essays in physiognomy (Plate II, Figure 2, p. 34a, Holocroft, 16th ed.). London: William Tegg.

Despite exhortations against the belief that character can be read from the face, you are in good company when you engage in face reading. This practice, called physiognomy, has persisted from ancient times to the present. In ancient Rome, the orator Cicero declared that “the countenance is the reflection of the soul.” In ancient China, Confucius said, “Look into a person’s pupils. He cannot hide himself.” In ancient Greece, a lengthy treatise on physiognomy, which has been attributed to Aristotle, described facial signs of psychological traits, such as the following:

Men with small foreheads are fickle, whereas if they are rounded or bulging out the owners are quick-tempered. Straight eyebrows indicate softness of disposition, those that curve out toward the temples, humor and dissimulation. The staring eye indicates impudence, the winking indecision. Large and outstanding ears indicate a tendency to irrelevant talk or chattering.2

Aristotle also drew analogies to animals, observing for example that “persons with hooked noses are ferocious; witness hawks.”3 Physiognomic principles, such as those espoused by Aristotle, were incorporated into Greek theater, where actors wore masks that represented certain types. These masks depicted not only characteristic facial expressions, but also characteristic facial structures. A man of sorrows, such as Oedipus, would have a long face.4 Clearly the ancient Greeks were able to use facial appearance as a basis for reading psychological traits, and many seem to have taken physiognomy very seriously. Indeed, the mathematician Pythagoras is reputed to have turned students away from his academy if their facial appearance was not suited to the profitable study of mathematics. One can only imagine the number of Euclids and Einsteins lost to civilization.

Darwin almost lost his passage on the Beagle because the captain was highly influenced by the Swiss physiognomist Johann Caspar Lavater (1741-1801), whose writings were widely read from the time his book Essays on Physiognomy was first published in 1772. This book was regularly reprinted for a hundred years in German, French, English, and Dutch, and two modern versions were published in Lavater’s home country of Switzerland as late as 1940, bringing the grand total to 151 editions in various languages. The eighth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica documented the enormous impact of this book on social interactions: “In many places, where the study of human character from the face was an epidemic, the people went masked through the streets.”5

Both the popularity of Lavater’s writings and the fear they evoked attest to the appeal of physiognomy, an allure that persists in contemporary society, although there is ambivalence. Just as people hid from the scrutiny of physiognomists in the heyday of Lavater’s influence, they remain wary of face-reading skills even today. Telling a stranger at a cocktail party that I study impressions of faces is a surefire way to end the conversation, even though studying impressions is not the same as actually reading character! A survey of university students suggested why people have this reaction: Over 90 percent believe that there are important facial guides to character.6 The consensus regarding what psychological traits a face reveals is so strong that it can serve as a basis for humor, as in the cartoons shown in Figures 1.2,1.3, and 1.4. Perhaps you can discern some common elements in the facial structure of the harmless-looking dog and man in two of these cartoons. Indeed, caricaturists work from the assumption that certain appearances can be manipulated as codes to create a psychological portrait that people can immediately recognize by reading elements of the code.

Daumier, one of the great masters of caricature, drew on the traditions of physiognomists to communicate the distinguishing traits of various social types among the bourgeoisie of nineteenth-century France—from the small shopkeeper and concierge to the politician, lawyer, and banker. Consider, for example, the banker shown in Figure 1.5. This caricature is meant to convey self-absorption and greed, as revealed by Daumier in the accompanying text: “He is the prototype of egoism, presumption and

Figure 1.2 Garfield. © 1984, 2993 Paws, Inc. Dist. by Universal Press Syndicate. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Figure 1.3 Fred Basset. Reprinted by permission of Tribune Media Services.

Figure 1.4 Garfield. © 1984, 2993, Paws, Inc. Dist. by Universal Press Syndicate. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

pride. He loves luxury, and apes the aristocracy which he aspires to displace.”7 The appearance of this banker bears a close resemblance to Lavater’s description of the appearance of selfish, greedy types as ‘large bulky persons, with small eyes, round full hanging cheeks, puffed lips, and a chin resembling a purse or bag;… who on every occasion consult their own ease without regard to others.”8

Figure 1.5 Daumier, The Banker. French Types (D 263, 1835). Brandeis University Libraries, Waltham, Massachusetts, the Benjamin J. and Julia M. Trustman Collection (Photo credit: David Caras).

Characteristic features recur in Daumier’s caricatures, and their meaning is often metaphorical. The fullness of the banker’s face and body represents the fullness of his coffers, and there may have been a kernel of truth in this representation in an era when corpulence was a sign of wealth. Similarly, the noses of Daumier’s gluttonous types are full and bulbous, and “the poor and modest worker, spare and lean, is typically shown with cheek bone casting its shadows on the hollows, in contrast with the well rounded jowl of the bourgeois.”9 Daumier’s use of metaphor is also shown in the lower foreheads of the lower classes and in the sharp noses of “sharp” critics and connoisseurs.

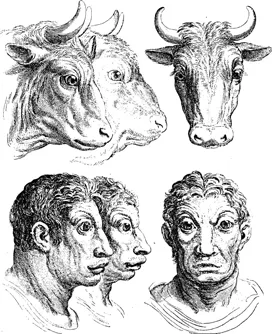

Comparisons of animals and humans codified by the seventeenth-century physiognomist Le Brun were also used by Daumier. Daumier’s faces of clergy and government officials have features based on the crow, as do Le Brun’s cheats, tricksters, and predators. Clergy were also depicted by Daumier as a cross between Le Brun’s donkey (boorish) and his ram (stupid). As shown in Figure 1.6, butchers resembled oxen.

Fine artists, like caricaturists, exploit the ability of the face to convey psychological traits. In fact, Lavater viewed his work as a sourcebook for artists, saying of the painter, “his art too evidently reproves the childish and arrogant prejudices of those who pretend to disbelieve physiognomy.”10 An examination of portraits, such as those by Rembrandt and Gauguin shown in Figure 1.7, upholds this view. You don’t merely perceive differences in face shape and feature size in these portraits; you also perceive differences in character. Rembrandt looks more approachable and flexible than Gauguin, a fact that must be somehow conveyed by facial structure, because the men wear similar facial expressions.

Figure 1.6 Metivet, Les Boeufs (1927). La Physionomie Humaine comparée à la Physionomie des animaux d’àpres les dessins de Le Brun. Paris: Librairie Renouard.

Leonardo da Vinci claimed that his portraits depicted “the motions of the mind.”11 His Mona Lisa, shown in Figure 1.8, is famous for the debates her face has inspired regarding what psychological machinations it reveals. Most have focused on her smile as the source of inferences about her psyche. The popular song asks is this a smile to charm a lover? to hide a broken heart? is it warm? is it real? Answers have ranged from the sublime to the ridiculous, but they reveal the range of information that people assume can be provided in a face. It has been said that the Mona Lisa is wearing the beatific smile of pregnancy, the smug smile of an unfaithful wife, the crooked smile of Bell’s palsy, and even the satisfied smile of a burp. The Chinese artist, Song Bin, who has painted numerous replicas of the Mona Lisa affirms the connection between her smile and her character, noting that “the corners of her mouth are still the hardest to portray… You must understand her status in society, her personality.”12

Figure 1.7 Rembrandt (left), Self-Portrait (1661). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Gawgwzn (right), Self-Portrait with Palette (1893-1894). Private collection, Acquavella Galleries, New York.

Literature, like the graphic arts, conveys psychological traits through facial depictions. The nineteenth-century writer Balzac, like his contemporary Daumier, was concerned with the classification of Parisian types: the bureaucrat, the lawyer, the social climber, the banker. His verbal portrayals of physiognomy were as vivid as Daumier’s pictorial ones. Balzac described the “idle rich” as follows:

Unrelieved boredom, this inanity of mind, heart, and brain, this weariness with the unending round of Paris receptions, all leave their mark on the features and produce these paste-board faces, those premature wrinkles, that rich man’s physiognomy on which impotence has set its grimace.13

His description of lawyers is not far removed from the current flurry of negative stereotypes:

What countenance can retain its beauty in the debasing exercise of a profession which compels a man to bear the burden of public miseries … they no longer feel, they merely apply rules which are stultified by particular cases … And so their faces present the raw pallor, the unnatural colouring, the lack-lustre eyes with rings around them, the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Judging a Book by Its Cover

- 2 What’s in a Face?

- 3 The Bases of Reading Faces

- 4 A Baby’s Face Is Disarming

- 5 The Boons and the Banes of a Babyface

- 6 Analyzing Attractiveness

- 7 The Advantages of Attractiveness

- 8 Formative Faces and Pulchritudinous Personalities

- 9 Phasing Out Face Effects

- 10 Unmasking the Face

- Notes

- About the Book and Author

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reading Faces by Leslie Zebrowitz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.