CHAPTER ONE

EXPLORATION IN THE ANCIENT WORLD

THE MEDITERRANEAN FULCRUM

SOME TEN THOUSAND YEARS AGO, on the plains of Mesopotamia and in the hills of Anatolia, certain groups of men developed the arts of agriculture, metal-working and building, and used them to create the earliest civilizations. These people were descended from a far older race of men who long before had learned to use stone tools, to control fire, and to speak. Those first humans are believed to have emerged from East Africa perhaps 100,000 years earlier, and from that point of origin to have migrated across the entire world, entering America and Australasia via now-vanished land bridges. In a biological sense therefore, the entire world was man’s home: as a species he had already travelled the earth. But this dispersal occurred before the beginning of human history, of man’s collective memory. Each emergent civilization as it came to consciousness – in Mesopotamia, China or America – was aware only of its own immediate environment. For thousands of years of human history this pattern was maintained, of multiple civilizations developing in isolation and in ignorance of each other. This isolation was the natural product of physical geography, the impassable barriers of ocean, desert and mountain.

The history of exploration is the process by which this isolation has been broken down, the process by which the one world which mankind now inhabits was created. In this process it is not solely the act of travel that is decisive, but man’s developing knowledge of the world, knowledge that becomes recorded, permanent, and above all centralized into one systematic view of the world. The European Age of Discovery remains all-important because of its scale and its completeness. It encompassed the entire world, drawing together for the first time a knowledge of Africa, Asia, the Americas and Europe, and of the oceans that now linked rather than divided them. For it was this power of ocean travel which distinguished the European explorers of the Renaissance from their predecessors: they were able to shape a new world order because they alone could range over the whole world. However great the geographical spread of earlier cultures – Roman, Arab, Mongol or Inca – vast areas of the world, indeed most of the world, had always remained unknown and inaccessible. It was the navigators of the sixteenth century who changed that forever: after Magellan, mankind was living, for better or worse, in a single world. In the Renaissance period the sudden explosion of geographical knowledge found its perfect expression in a newly-created icon: the map. For the monarch and the navigator, the merchant and the scholar, the map became a mirror of the world, both a symbol of knowledge and an instrument of power, and it now acquired an importance in European intellectual and political life which it had never enjoyed in any other culture. It became both a record of what was known, and a spur to probe the unknown. Its roots lay partly in science and partly in fable, and it promised both wealth and knowledge. The map was a meeting-place between the known and the unknown: only when the limits of geographical knowledge had been defined on a map could explorers set out in search of new lands, new routes and new knowledge.

After 1500 the history of exploration resolves itself into the history of European geographical knowledge, and it was in European maps that a decisive revolution in geography found its expression. There was a finality and irreversibility about these major discoveries – the circumnavigation of Africa, the crossing of the Atlantic and of the Pacific – for they created the modern world map, as surely as Copernicus created the modern cosmic map. In the years between 1480 and 1530, knowledge and power went hand in hand as intellectual, political and technical forces carried Europeans to Africa, Asia and America as traders or conquerors. The European culture of the later middle ages had not shown itself inherently greater or wiser or more powerful than the world of Islam or the Mongol empire; yet a few decades at the end of the fifteenth century saw a handful of radical ideas in geography and technology merge to create an explosive movement which enabled western Europe to outpace all rival cultures. The compass, the three-masted ship, the map and the gun – these were the weapons of the European explorers. Fifty years ago the Age of Discovery was chronicled in books with titles such as The Conquest of the Earth, or Nine Against the Unknown, or Founders of Empire, and so on. Such titles acknowledged the unique importance of these events, but today we are less triumphalist: we know that Columbus did not discover America, since there were some twenty million people living on the continent when he arrived. What he clearly did however, was to bring America into the sphere of European knowledge – with momentous consequences for the peoples of both continents. Furthermore he and the other great mariners of these early years inaugurated an era in which geographical knowledge – and the technical power to exploit it – acquired massive political importance.

Many earlier civilizations had been expansive in character: Greeks, Romans and Moslems had all pushed outwards from their historic centres, in pursuit of trade or conquest. These movements had been halted by natural obstacles, or by an opposing force strong enough to stop them. Certain other cultures, however highly developed, had remained fixed in their homeland; the Egyptians, the Maya, the Chinese (save for one short-lived experiment in the fifteenth century) were apparently not tempted intellectually or militarily to venture far beyond their own boundaries. On the eve of the European conquests, the Aztec and Inca civilizations had absolutely no mutual knowledge or contact. Later, when European ships thronged the harbours of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, no Indian or Chinese ship was ever seen in Seville, Amsterdam or London. Why certain cultures were geographically dynamic and others static can never be entirely explained, nor can the impulse to build experience into systematic knowledge, an impulse completely absent from some societies. Before the European Age of Discovery, the most dynamic culture in the world was that of the Polynesians, whose migrations carried them across millions of square miles of the Pacific. Yet, in that pre-literate and pre-scientific culture, these voyages were not built into a coherent body of geographical knowledge. Once the voyagers had settled a new group of distant islands, there was apparently no further contact with their place of origin, and each community then developed in isolation, nor was there any cartographic tradition among these remarkable seafarers.

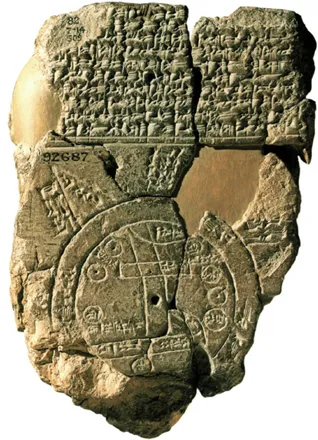

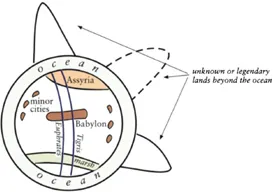

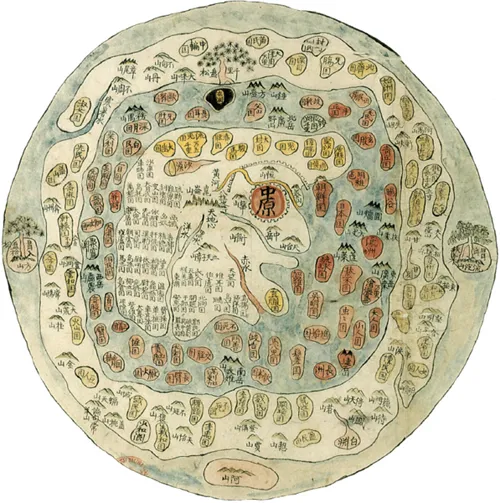

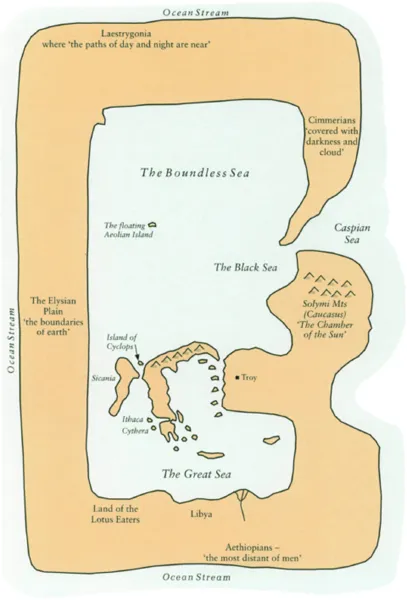

The Polynesian experience is diametrically opposed to that of the ancient Hellenic people: although far more restricted geographically, they built up a body of objective geographical knowledge that was recorded and permanent. This tradition was eclipsed in the post-classical era, but was later to be rediscovered and became a decisive influence in shaping the geographical ideas of the Renaissance navigators. The most celebrated early Mediterranean seafarers, the Phoenicians, had, before 1000BC, sailed from their homeland in Canaan beyond the Pillars of Hercules, perhaps as far as Britain, and colonized the coasts of Spain and North Africa. Yet of their science, geography and chartmaking, if any, we know nothing. The secrets of their routes and their maritime knowledge were jealously guarded. They transmitted their skills through traditional, oral means, and as far we can tell formal cartography played no part in their maritime achievement. It was the Greeks who left the fullest record of the transformation of geographical experience into formal knowledge. Weaving together travel narratives, rational observation and scientific theory, Greek thinkers addressed the three most fundamental questions of geography: What is the form and magnitude of the earth? What are the shape and size of its land-masses and oceans? What is the nature and extent of human habitation on the earth? There is considerable fragmentary evidence that many ancient civilizations had regarded ‘The World’ as synonymous with ‘Our World’. Egyptians, Baylonians, Indians and Chinese have all left ‘World Maps’ which are essentially maps of their own territory, surrounded by ocean. This was a natural concept, and the same thought is traceable in a number of ancient texts, such as the Homeric poems. These peoples plainly did not possess a world map – literally or psychologically – in which certain blank spaces were waiting to be filled; rather, what they knew filled the whole world. It was the achievement of certain Greek thinkers to break free from such subjective intuitions and to raise geography to the level of objective science.

Babylonian World Map, clay tablet C.600BC.

B.M. Dept. of Western Asiatic Antiquities

The Babylonian World Map re-drawn: the Near East is regarded as the world, surrounded by ocean, with rumours of distant lands beyond.

Chinese World Map c. 1500AD. China is shown as the Middle Kingdom, with the rest of the world at its edges. Note the structural similarity to the Homeric World Map opposite.

The British Library Maps 33.c.13.

The Homeric World: a conjectural reconstruction taken from geographical references in the ‘Iliad’ and the ‘Odyssey’. Sometimes distances were indicated by sailing times, e.g. a north wind drove the Greeks for ten days from Cythera to the land of the Lotus Eaters.

A shipwreck in the eighth century BC, drawn on a vase found on Ischia, near the Bay of Naples, site of the first Greek colony in the west.

By permission of Oxford University Press

The earliest documents of European history, the Homeric poems, display a pre-scientific geography. The known world was small and enclosed, for beyond the shores of the eastern Mediterranean were the regions of the Ethiopians, the Elysian plains, or the Cimmerian darkness, regions which were legendary yet which were traditionally assigned vague locations to the south, west or north of the Aegean heartland. The extensive Hellenic colonization of the Mediterranean and Black Sea coasts between 800BC and 400BC opened up this archaic world. Countless forgotten traders or warriors must have explored the hinterlands, dispelling uncertainty and legend. More distant lands became known through single, epic journeys, related by classical writers such as Herodotus, whose stories often exercised great influence on later explorers. Herodotus reports for example that five unnamed adventurers journeyed south-west from Libya across a vast desert until they reached a great river flowing from west to east. This was presumably the Niger, although Herodotus considered it was the Nile. Perhaps his most famous and intriguing story was of the Phoenicians who had sailed around the entire coast of Africa about the year 600BC. Equally celebrated was the great northern voyage of Pytheas from Marseilles to Britain and beyond. This journey, known to us through the later account of Strabo, took place about 300BC, and was the source of all Greek and Roman knowledge of northern European geography until the time of Julius Caesar. Pytheas may have circumnavigated Britain, sailed the Baltic and the North Sea, and touched the coast of Norway or even Iceland. The identification of his ‘Thule’, the northerly limit of the world, is uncertain, but he reported that the midsummer day there lasted 24 hours, and that these lands at some 65 degrees north, were fully inhabited, contrary to the prevailing Greek belief that human settlement must stop short of this ‘frigid zone’. To the east, around 510BC Darius, King of Persia, sent a Greek envoy, Scylax of Caryanda, to explore the Indus and beyond. Scylax travelled overland to the Kabul River and descended the Indus to the sea, before sailing westward to coast the Arabian Peninsula and ascend the Red Sea. He was the first known European to see India, and knowledge of his journey was the inspiration for that of Alexander the Great. Such journeys however were isolated and unrepeated, and the knowledge they brought remained uncertain, almost legendary. Yet their currency seems to show that classical thinkers were quite open to the possibi...