![]()

PART 1: TEXTS AND MEANINGS IN COMMUNICATION

I don’t dig this brooding analytical stuff. I just danced; and I just acted.

(Fred Astaire)

1 WHAT’S THE TOPIC? Approaching theory WHAT’S THE TEXT? Peter Barry Beginning Theory

Experienced and confident students of Communication Studies assert that it is misleading to distinguish between theory and practice. Nevertheless many commentators find such a distinction useful. One way of characterising the discipline is that it consists of practices which are informed by theory. As Communication Studies students we subject the world of communication to various kinds of analysis prompted, guided and shaped by those theoretical pioneers who have gone before. Given the multi-disciplinary character of the subject this results in our drawing on the broadest range of useful theoretical work: philosophical, linguistic, anthropological, psychological, sociological, aesthetic. Because the discipline draws on work originally written in languages other than English we are thus at the mercy of translators.

This book is a collection (and, necessarily, a selection) of readings which we hope will represent a coming together of theory and practice, in which theory becomes a means of expression, a way through to meanings, a bridge. Often before it becomes this bridge, theory will first function as a barrier – both semantic and psychological. In other words you’re put off because you think you can’t understand it and then lose confidence as a result of feeling stupid. Peter Barry, writing specifically for students of literature, addresses this in the introduction to his book Beginning Theory. This is good advice for all prospective students on an Arts, Humanities, or Social Sciences programme, and it’s particularly useful for Communication Studies students.

I want to assure you at the outset that the doubts and uncertainties you will have about this material are probably not due to:

1. any supposed mental incapacity of your own, for example, to your not having ‘a philosophical mind’, or not possessing the kind of X-ray intellect which can penetrate jargon and see the sense beneath, or

2. the fact that your schooling did not include intensive tuition in, say, linguistics or philosophy, or

3. the innate and irreducible difficulty of the material itself (a point we will come back to).

Rather, nearly all the difficulties you will have will be the direct result of the way theory is written, and the way it is written about. For literary theory, it must be emphasised, is not innately difficult. There are very few inherently complex ideas in existence in literal theory. On the contrary, the whole body of work known collectively as ‘theory’ is based upon some dozen or so ideas, none of which are in themselves difficult.… What is difficult, however, is the language of theory. Many of the major writers on theory are French, so that much of what we read is in translation, sometimes of a rather clumsy kind. Being a Romance language, French takes most of its words directly from Latin, and it lacks the reassuring Anglo-Saxon layer of vocabulary which provides us with so many of our brief, familiar, everyday terms. Hence, a close English translation of a French academic text will contain a large number of longer Latinate words, always perceived as a source of difficulty by English-speaking readers. Writing with a high proportion of these characteristics can be off-putting and wearying, and it is easy to lose patience.

But the frame of mind I would recommend at the outset is threefold. Firstly, we must have some initial patience with the difficult surface of the writing. We must avoid the too-ready conclusion that literary theory is just meaningless, pretentious jargon (that is, that the theory is at fault). Secondly, on the other hand, we must, for obvious reasons, resist the view that we ourselves are intellectually incapable of coping with it (that is, that we are at fault). Thirdly, and crucially, we must not assume that the difficulty of theoretical writing is always the dress of profound ideas – only that it might sometimes be, which leaves the onus of discrimination on us. To sum up this attitude: we are looking, in literary theory, for something we can use, not something which will use us. We ought not to issue theory with a blank cheque to spend our time for us. (If we do, it will certainly spend more than we can afford.) Do not, then, be endlessly patient with theory. Require it to be clear, and expect it, in the longer term, to deliver something solid. Don’t be content, as many seem to be, just to see it as ‘challenging’ conventional practice or ‘putting it in question’ in some never quite specified way. Challenges are fine, but they have to amount to something in the end.

(Barry 2002: 6–8)

One line leaps out as a perfect introduction to something that purports to be ‘the essential resource’: ‘We are looking … for something we can use, not something that will use us’. Let this be true of both you and us.

2 WHAT’S THE TOPIC? Perception, perspective, and the character of images WHAT’S THE TEXT? John Berger Ways of Seeing

In Bean: The Ultimate Disaster Movie Rowan Atkinson’s hapless character is mistaken for a leading English art expert at an American gallery (in fact he is merely a security guard). At the end of the film he is required to give a lecture to celebrate the fact that the gallery has acquired the famous American painting ‘Whistler’s Mother’. The audience, knowing Bean’s near incapacity with words, can see no way out for him: he will be exposed. However, to much applause, he begins by explaining, ‘I sit and look at the paintings’. (An earlier generation of filmgoers had witnessed something similar with Chance the Gardener, the Peter Sellers character, in Hal Ashby’s 1979 film of Jerzy Kosinski’s novel Being There, where Chance’s banal utterances are taken for profound philosophy.)

Beyond the irony are the opening questions of any textual analysis:

how is it organised? and,

John Berger’s book Ways of Seeing begins by addressing some of these issues. Berger is mainly concerned with those special pieces of communication to which we give the collective title ‘Art’ but his approach is extremely useful to any student of communication. The first of the seven essays which comprise the book begins with a provocative assertion: ‘Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognises before it can speak’. This is a provocative statement, one that many psychologists would want to refute. Indeed, there is much speculation as to whether seeing comes before words just as much as whether the spoken word precedes the written. Taking his lead from Korzybski’s concept of General Semantics William S Burroughs reflects (in the introduction to ‘The Book of Breeething’): ‘It is generally assumed that the spoken word came before the written word. I suggest that the spoken word as we know it came after the written word’ (1979: 65). What Berger offers is a contribution to the debate as to what is communication and where communication starts. Berger puts seeing at the centre of this discussion; other commentators beg to differ.

Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognises before it can speak.

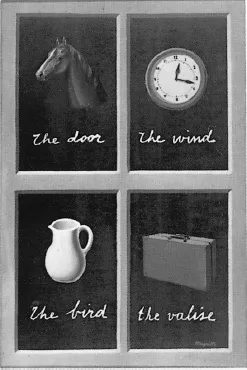

But there is also another sense in which seeing comes before words. It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Each evening we see the sun set. We know that the earth is turning away from it. Yet the knowledge, the explanation, never quite fits the sight. The Surrealist painter Magritte commented on this always-present gap between words and seeing in a painting called The Key of Dreams.

The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe. In the Middle Ages when men believed in the physical existence of Hell the sight of fire must have meant something different from what it means today. Nevertheless their idea of Hell owed a lot to the sight of fire consuming and the ashes remaining – as well as to their experience of the pain of burns.

When in love, the sight of the beloved has a completeness which no words and no embrace can match: a completeness which only the act of making love can temporarily accommodate.

Yet this seeing which comes before words, and can never be quite covered by them, is not a question of mechanically reacting to stimuli. (It can only be thought of in this way if one isolates the small part of the process which concerns the eye’s retina.) We only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice.

As a result of this act, what we see is brought within our reach – though not necessarily within arm’s reach. To touch something is to situate oneself in relation to it. (Close your eyes, move round the room and notice how the faculty of touch is like a static, limited form of sight.) We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves. Our vision is continually active, continually moving, continually holding things in a circle around itself, constituting what is present to us as we are.

Soon after we can see, we are aware that we can also be seen. The eye of the other combines with our own eye to make it fully credible that we are part of the visible world.

If we accept that we can see that hill over there, we propose that from that hill we can be seen. The reciprocal nature of vision is more fundamental that that of spoken dialogue. And often dialogue is an attempt to verbalize this – an attempt to explain how, either metaphorically or literally, ‘you see things’, and an attempt to discover how ‘he sees things’.

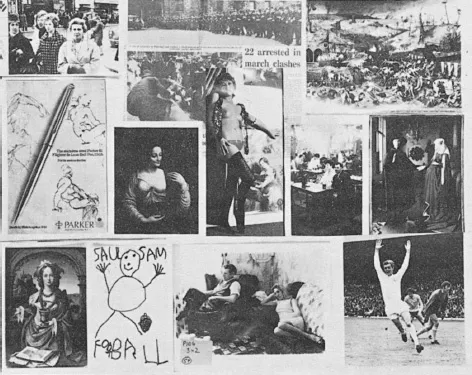

In the sense in which we use the word in this book, all images are man-made.

An image is a sight which has been recreated or reproduced. It is an appearance, or a set of appearances, which has been detached from the place and time in which it first made its appearance and preserved – for a few moments or a few centuries. Every image embodies a way of seeing. Even a photograph. For photographs are not, as is often assumed, a mechanical record. Every time we look at a photograph, we are aware, however slightly, of the photographer selecting that sight from an infinity of other possible sights. This is true even in the most casual family snapshot. The photographer’s way of seeing is reflected in his choice of subject. The painter’s way of seeing is reconstituted by the marks he makes on the canvas or paper. Yet, although every image embodies a way o...