![]()

PART ONE

INTRODUCTION Conceptual and Historical Background

An introduction to the study of international relations in our time is an introduction to the art and science of the survival of mankind.

—Karl W. Deutsch, The Analysis of International Relations, 1988

Don’t be like the student who was asked, “Which is worse, ignorance or apathy?” and who responded, “I don’t know and I don’t care!”

—Charles Yost, former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, 1980

![]()

1

Understanding

International Relations, or

Getting a Handle

on the World

The twenty-first century will encompass the longest period of peace, democracy, and economic development in history.

—Allan E. Goodman, A Brief History of the Future, 1993

The threat of self-destruction and planetary destruction is not something that we will pose one day in the future, if we fail to take certain precautions; it is here now, hanging over the heads of all of us at every moment.

—Jonathan Schell, The Fate of the Earth, 1982

It is always hard to predict anything, especially the future.

—Romanian proverb

THE CHALLENGE

This is a book about international relations in the twenty-first century. It is meant to introduce the subject and distill its key features, although even a basic primer on world affairs today necessarily involves the student in the study of perplexing problems that are as challenging as they are interesting. Indeed, the author’s task here is not to simplify the world but rather to make the reader appreciate, and ultimately understand, its great complexity. We are still in the early stages of the new millennium. No generation will experience such a profound moment of reflection about the human condition for another thousand years. Hence we would seem to have a special obligation to think not only with caring but, more importantly, with carefulness and clarity about the nature of the current world order or, as some might say, disorder. This requires us to think about the past as well, since “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”1 On the importance of this subject, it has been said that “an introduction to the study of international relations in our time is an introduction to the art and science of the survival of mankind.”2

Professors, policymakers, and publics in the United States and throughout the globe are faced with many puzzles that are not easily answerable, whether through artful speculation or, even less so, through controlled experiments conducted in white lab coats. For example, note the question posed by political scientist John Ikenberry that is on the minds of many contemporary observers:

The rise of China will undoubtedly be one of the great dramas of the twenty-first century. China’s extraordinary economic growth and active diplomacy are already transforming East Asia, and future decades will see even greater increases in Chinese power and influence. But exactly how this drama will play out is an open question. Will China overthrow the existing order or become a part of it? And what, if anything, can the United States do to maintain its position as China rises?3

Ikenberry argues that this situation is comparable to great power transitions in the past, and that it can be managed peaceably as long as the United States adopts enlightened policies. An alternative viewpoint is presented by Parag Khanna, who sees an emergent “Big Three,” with the United States having to compete for dominance with both China and Europe (the European Union) in what is “for the first time in history” a “global, multicivilizational, multipolar battle,” whose outcome may not be as sanguine as Ikenberry suggests.4

How does one answer the question raised by Professor Ikenberry? What are we to make of the world in the early twenty-first century? There is great uncertainty about the United States-China relationship and other dramas being played out on the world stage; how will these evolve, with what denouement? Henry Luce, the founder of Time magazine, writing between World War I and World War II, famously declared the twentieth century “the American century.” Will the twenty-first century also be the American century? Or will it be the Chinese century, the European century, or a “post-international politics” century altogether?5 In the 1970s U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger asked Chinese leader Chou En-Lai what he thought of the 1789 French Revolution. He replied, “Too soon to tell.” It is especially premature to judge the long-term implications of events occurring in the 2000s, although in the nuclear age we may not have the luxury of sitting back and waiting a couple hundred years for a final verdict on their meaning. We may have to think, and act, now.

Few observers, including scholars, have done a good job of correctly assessing and anticipating events of late. I vividly recall sitting in a paneled room at the International Studies Association (ISA) annual meeting in Washington, D.C., in the spring of 1987, attending a session featuring two American diplomats engaging two Russian diplomats in a speculative discussion about “the future of U.S.-Soviet relations.” This was at a time when the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union was still raging, when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had just come to power in Moscow, when U.S. president Ronald Reagan was continuing to characterize the USSR as an “evil empire” bent on spreading global communism, and when his secretary of defense said that “we are no longer in the postwar era but the prewar era.” One of the Russian diplomats began his comments by uttering what he took to be an old Romanian proverb, that “it is always hard to predict anything, especially the future.” Indeed, who in that room, or for that matter any room anywhere that day, can claim to have predicted that within a half decade the world would witness the end of the Cold War and the end of the Soviet Union itself, with hardly a shot being fired? Most people—scholars, practitioners, and laypersons alike—shared former Carter administration national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski’s 1986 assessment that “the American-Soviet conflict is not some temporary aberration but a historical rivalry that will long endure.”6 Yet by December 1989, the Berlin Wall that had symbolized the Iron Curtain separating the free and nonfree worlds had collapsed, and the Soviet Red Army Chorus could be heard in Washington, D.C., leading Reagan’s successor and a throng of dignitaries at a Kennedy Center gala in a stirring rendition of “God Bless America.” By December 1991, the USSR had dissolved into Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and assorted other independent republics. As Gorbachev proclaimed that “the world is leaving one epoch, the Cold War, and entering a new one,” President George H.W. Bush proclaimed a “new world order” of peace and harmony. 7

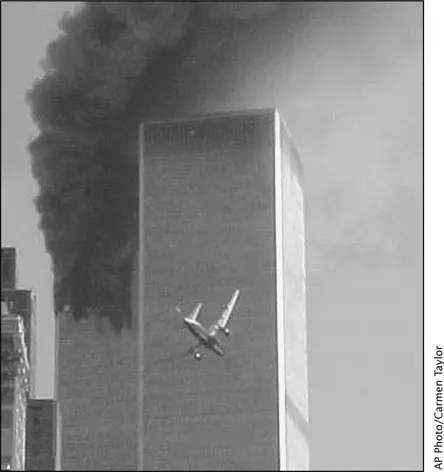

At that very moment, amid much fanfare and jubilation, Francis Fukuyama of the U.S. State Department wrote that we were witnessing “the end of history,” as the forces of Western liberal democracy and free market capitalism had seemingly achieved their final triumph over all other competing ideologies.8 Although not everyone agreed, there was a general sense that those ideas were on the march worldwide.9 But the “holiday from history” was short-lived, as was the jubilant mood.10 If 11/9 (the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989) had been earthshaking, 9/11 was no less so: on September 11, 2001, some 3,000 people lost their lives when al Qaeda terrorists attacked the World Trade Center in New York City, leading many to wonder whether the post–Cold War era had abruptly ended and had given way to a new, as yet unnamed era. Euphoria suddenly turned to despair and a doom and gloom view of the future.

Humanity, then, in the recent past has lurched wildly between the extreme mind-sets of heaven one minute and hell the next. Despite our failure to predict even five-year trends, long-term forecasting remains a growth industry. Prognosticators have offered both optimistic and pessimistic prophecies. In addition to Fukuyama, the optimists in the post–Cold War era have included Alan Goodman, whose A Brief History of the Future heralded the twenty-first century as an era that “will encompass the longest period of peace, democracy, and economic development in history.” Another observer echoes Goodman in noting that “the series of positive trends over the last 20 years” have created “an international climate of unprecedented peace and prosperity” in much of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, while another contends that we are witnessing the “obsolescence of major war” and that terrorist threats are “overblown.”11 The ranks of the pessimists include John Mearsheimer, who, a year after Fukuyama’s pronouncement, was already lamenting “why we will soon miss the Cold War” (since he expected the historical inevitability and “tragedy” of great-power politics would take an even more virulent turn in the future), and Samuel Huntington, who hypothesized that “the clash of civilizations” pitting “the West versus the rest” (Islamic fundamentalism and other cultures) would be the successor to the East-West ideological axis of conflict that ended in 1989. Another commentator wrote of “the coming anarchy” and the “shattering of the dreams of the post–Cold War era,” stemming from ecological and other catastrophes, citing the recent genocidal conflicts in Africa as a metaphor for how both the South and North will evolve.12 Many other writers have contemplated what the future holds in terms of great-power relationships and other developments, including Ikenberry and Khanna, mentioned above.

A tale of two cities: The fall of the Berlin Wall on 11/9 and the attack on the World Trade Center in New York on 9/11—Is it the best and worst of times?

It is hard to get a handle on the world today, and especially difficult to know whether to feel good or bad about its current state, partly because, to borrow Charles Dickens’s much-quoted 1859 saying, it arguably is the best of times and the worst of times. Suffice it to say, life expectancy in most countries extends beyond anything imaginable in Dickens’s day, even as the entire human species can now be extinguished in a matter of hours and maybe minutes. We have the potential for unprecedented international cooperation (the United Nations, despite its many flaws, represents the most ambitious attempt at global institution-building in the million years that Homo sapiens has inhabited the earth) as well as unprecedented international conflict (in the words of one commentator, “it has historically been one thing to die for your country” but, in the event of a major war in the nuclear age, “it is a different thing to die with your country”).13

On the one hand, one might be forgiven for thinking that Alan Goodman’s prediction above is far too optimistic. After all, the twentieth century saw the worst carnage in human history, with over 100 million people killed in wars, a record that might be dwarfed in the future as ABC (atomic, biological, and chemical) weapons—WMDs (weapons of mass destruction)—all are on the brink of proliferating dangerously; biological and chemical weaponry (the “poor person’s nuclear bomb”) is relatively easy to develop and especially liable to end up in the hands of terrorists. As for poverty, there remain a huge number of poor people in the world, partly as a function of an ongoing population explosion in many less developed countries and partly because of a growing rich-poor gap that finds almost 3 billion persons living on less than $2 a day. The onset of a global financial crisis in 2008–2009, which saw wild swings in the U.S., European, and Asian stock markets, only served to exacerbate economic anxieties, even among the rich. In many countries, human rights violations remain prevalent, including cases of genocide. If humanity is not exterminated by the arms buildup of WMDs, it may happen instead through the buildup of CO2 and other greenhouse gases in the earth’s atmosphere that are contributing to global warming, making the last two decades since 1990 the warmest on record.14

On the other hand, the glass would seem at least as half full as half empty. Almost no one currently alive has had to cope with sustained crises of the magnitude experienced by my parents’ generation, which in successive decades spent the flower of their youth suffering through World War I (1914–1918), the Great Depression (1929–1939), and World War II (1939–1945). Even amid grinding poverty, average income per capita in developing countries has been rising over the past twenty years while infant mortality and illiteracy have been declining. Globalization of the international economy promises a better life for more consumers if economic growth with equity and with environmentally sustainable development can be promoted and world financial crises stabilized.15 Recent decades have seen impressive gains in the area of democratization, repressive regimes notwithstanding; the latest Freedom House report counts ninety countries as “free” (representing roughly half of the global population), sixty “partly free,” and forty-three “not free,” with the number of free countries being the highest in the history of the thirty-five-year survey.16 The president of Harvard University summed up “the remarkable opportunities inherent in the current global moment” in a recent commencement address:

For the first time in all of human history, a majority of people now live in countries where leaders are democratically elected, where women are treated as full citizens, and where the press is free. … Despite all the tragedies of war that rightly preoccupy us, the fraction of the world’s population killed each year in wars has, in recent times, been more than 95 percent lower than the comparable fraction for an average year of the 20th century.17

Amid the nightmarish possibilities relating to WMDs, it is worth remembering that the Cold War following World War II was just that, a nonhot, nonshooting war. In some important respects, the period since 1945 has been relatively peaceful and has even been characterized as “the long peace,” the longest continuous stretch of time since the beginning of the modern state system (in the seventeenth century) in which there has not been a single recorded instance of direct great-power exchange of hostilities.18 The probability of a war occurring between great powers today is perhaps closer to zero than at any point in history. That isn’t to say it couldn’t happen, only that it is a remote possibility. This is no small accomplishment. If only we could say the same for interstate wars involving not-so-great powers, as well as intrastate (civil) wars and extrastate violence perpetrated by terrorists, all of which remain major concerns, especially as the specter of WMD proliferation threatens to blur the distinction between who is or is not a “great power” capable of causing great harm to its neighbors and the world as a whole. For the United States, the “long peace” is precariously juxtaposed against the “long war” (the U.S. Defense Department’s name for the global fight against al Qaeda and international terrorism), as it awaits the possibility of another 9/11 attack.

We cannot know for sure where humanity is headed—how various dramas will play out—precisely because it depends in large measure on what choices policymakers and citizens make across the globe. One hopes those choices are informed choices, grounded in knowledge more than ignorance. As noted above, we are obliged to make every effort to think critically about international relations in order to improve our understanding and our capacity to shape things in a positive direction. This book tries to convey what is known and theorized about in the field of international relations, including core concepts and findings developed by political scientists, and to prod students to more deeply explore the subject. Chapter 1 discusses what exactly “international relations” (IR) is, offering a definition, and what approaches have been used to make sense of it, offering competing perspectives that can help us better describe and explain such phenomena. However, before we examine those issues, we need first to dispose of one other matter: Why bother studying IR? The answer may se...