![]()

1

TALKING ABOUT THINKING

Words are clues to the things people believe to be important. Societies that regard horses, or snow, or clouds, as significant parts of their lives, for example, have a multiplicity of words for different kinds of horses, snow, or clouds. On this basis, thinking must be a major concern of speakers of English. There is a sea of words that refer to thinking—and it will be useful to scan the semantic horizon before plunging in.

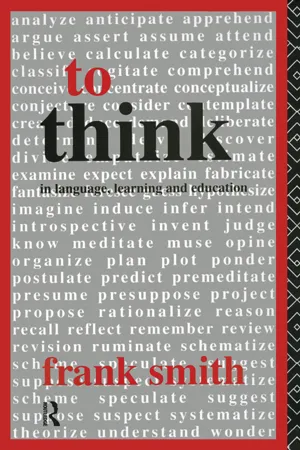

THINKING—IN SEVENTY-SEVEN WORDS

Here is a brief and incomplete list of English verbs related to thinking:

analyze

anticipate

apprehend

argue

assert

assume

attend

believe

calculate

categorize

classify

cogitate

comprehend

conceive

concentrate

conceptualize

conjecture

consider

contemplate

create

deduce

deem

deliberate

determine

devise

discover

divine

empathize

estimate

examine

expect

explain

fabricate

fantasize

foresee

guess

hypothesize

imagine

induce

infer

intend

introspect

invent

judge

know

meditate

muse

opine

organize

plan

plot

ponder

postulate

predict

premeditate

presume

presuppose

project

propose

rationalize

reason

recall

reflect

remember

review

revise

ruminate

schematize

scheme

speculate

suggest

suppose

suspect

systematize

theorize

understand

wonder

The list is illustrative, not exhaustive. I have deliberately excluded uncommon or exotic words like animadvert, brood, fancy, hazard, lucubrate, soliloquize, trow, and ween. And I have also left out some words that might in particular contexts imply thinking—such as exploring, outlining, and sketching—and a host of others that relate to more conspicuous activities, like reading and writing, although thinking must certainly be at the heart of them.

There are many ways in which my seventy-seven “thinking” words could be organized, apart from the rather unimaginative (unthinking?) alphabetical order that I have employed. The words could be grouped on a temporal basis. Some look back on past events: deduce, explain, recall, reflect, remember, review, and revise. Some project into the future: anticipate, conceive, divine, expect, foresee, imagine, intend, plan, plot, predict, project, and scheme. Others seem mostly concerned with what is going on at the moment (although the present is never entirely free of past or future connotations): analyze, argue, assert, assume, attend, believe, categorize, classify, comprehend, concentrate, conceptualize, determine, empathize, estimate, examine, invent, judge, know, opine, organize, presume, propose, reason, suggest, suspect, and understand.

Some of the words seem to be anchored in the substance of actual events, like concentrate, explain, and reason, while others are more concerned with possibilities, or impossibilities, like fantasize, imagine, and theorize. Some pairs of words are opposite in meaning, such as reason and guess, or remember and anticipate. Some words suggest things done quickly, while others entail deliberation; some concern specifics and others generalities; some imply a self-evident conclusion while others indicate uncertainty. There is little that all the terms have in common—except that in sentences they can usually be replaced by the word “think” or a term like “thinking about,” together with a few other words of elaboration.

WHAT THE WORDS REFER TO

The seventy-seven words also have in common the fact that they refer to things that people do. They describe activities of people, not of their brains. While the brain is normally regarded as the organ of thought, “thinking” words do not—except indirectly and implicitly—refer to what the brain is doing. The words all presuppose that something is going on in the brain (rather than in the liver or the lungs), but they do not specifically refer to what is going on in the brain. They refer to what the person is doing.1

We would not normally say that our brain is learning French, or pondering the world economy—we would say that we are doing those things. Even for something that transpires totally within the privacy of the head, like imagining, we would usually say that we, not our brains, are doing it. Normally I would say that “I” am remembering, considering, or feeling overwhelmed by something (just as I would normally say that I was digesting my dinner, rather than that my digestive system was doing so on my behalf). If I do say that my brain is remembering, considering, or overwhelmed by something, I am employing a figure of speech—or constructing an argument that I want to be taken as analytical and scientific. I am speaking in a special kind of context.

The seventy-seven words are all useful, and the English language would be poorer without them. Few of the words are synonymous with each other, and as I have demonstrated, some are mutually contradictory. But because English can find employment for at least seventy-seven words to make different kinds of statements about what people do when they think, it does not follow that there must be seventy-seven different kinds of thinking for the brain to do. Words are not a psychological theory, and they provide no clues to the nature of mental activity. There are scores of different words for ways of preparing and consuming meals, but not scores of different ways of digesting them.

There is usually no mystery about any of the seventy-seven words. We do not normally have to ask what they mean when we hear them in conversation, or read them in a novel. We can imagine what people are doing when the words are applied to them; we can even make assumptions about why they are doing those things, about their purposes and motivation.

If you tell me you are thinking about a meal we had together, I imagine the food that was on the table, not the mental activity that is currently occupying your brain. If you tell me that my friend George is anticipating, or arguing, or planning something, I picture him doing it. I do not picture something going on in his head, even when he is doing something utterly private and inconspicuous, like meditating or contemplating. In that case I imagine him sitting in a chair with a reflective look on his face, or something like that.

None of the “thinking” words produces an image of any kind of brain activity. In fact I have no idea what is going on in anyone’s head when these various manifestations of thought are engaged in, except that it must be relevant to what the person is doing. Chemical and neural changes take place in the brain all the time, but such changes are not part of my understanding of the words. Neuroscientists scan or probe the brains of their patients in a variety of ways, but they can never see what the patients are thinking. They have no idea whether the patient is analyzing, remembering, reflecting, and so on. To find out, they have to ask the thinker, or observe the person as a whole.

We cannot even look into our own brains to see what they are doing when we think, any more than we can look into our own eyes to see what is happening when we see. But that does not make the language of thinking difficult to understand. The language of thinking is not about brains, but about people.

Part of the mystique surrounding the word thinking may come from the curious fact that people usually only say they are thinking when they look as though they are doing nothing at all. We will say “I’m thinking” if we are not reading, writing, cooking an omelette, watering the plants, watching television, or doing anything else which is conspicuous and self-evident. If we were doing any of those other things, that is what we would say we were doing. But that does not mean that we are not thinking if we are doing something else. On the contrary, reading, writing, cooking, and even watching television involve thinking (although we might read or watch television to avoid thinking about something else that we ought to be attending to). When something self-evident is being done, thinking is taken for granted. Even an activity that appears to be habitual, like watering the plants or walking to the corner store, requires that thought be exercised if it is to be done appropriately, and terminated at the proper time.

It is obvious that thinking must be part of all other activities, because we would never say that we are doing them and thinking as well. It would be ridiculous for me to say that I am reading and thinking, and rude for me to suggest that you should read and think, because it is assumed that the thinking will take place. In the technical language of linguistics, thinking is a presupposition of reading, writing, and watching television. Watering the plants presupposes thinking about watering the plants.

We might occasionally say “You should think about that book you are reading,” but that would mean that the book has a particular significance (to us, at least), and we think the reader should pay additional attention to some aspects of it. We are not suggesting that the person would not normally be thinking during the reading, but that the reader should think about particular things. We might say “You should think where you are watering” when the water is going onto the floor rather than into the planter, but we would not normally say “I’d like you to water the plants and to think about where you are watering”—the thinking is presupposed; it is taken for granted.

So here is one situation when we say we are thinking—when we are not evidently doing something else. But if we are thinking, and not conspicuously doing something else, what are we actually doing? Consciously, we are imagining something we might actually be doing or have done—rehearsing a speech, remembering a movie, anticipating a meeting or a meal. Unconsciously, we are going through all the thinking that would underlie actually making a speech, watching a movie, having a meeting or a meal.

In other words, we say we are thinking when we are imagining doing something, in the head, removed from action. Otherwise we say we are doing the thing that involves the thinking. There is no difference from a thinking point of view. Doing something and thinking of doing something are inseparable. The only distinction is that when we do something conspicuously, so that other people can or could see us doing it, we are unlikely to use a thinking term, while if we do it surreptitiously, in the privacy of our own head, we call it thinking. We cannot do things without thinking, and we cannot think without contemplating doing things. Thought is action, overt or imagined.

The other confusing thing about the word thinking is that it is a “default term.” It tends to be used in a very general and imprecise sense when we cannot think of or be bothered to use a more precise word (just as I could have written remember rather than think of in this sentence). Rather than being regarded as an impressive, high-status term, thinking should perhaps be relegated to the same category as the useful but very general and imprecise term thing. Linguists talk about such words as “place-holders.” We talk about “the thing over there” when we cannot say anything more definite about whatever the thing is, or when we are postponing making a more definite statement. The same often applies when we talk about thinking, which is not a precise term, but is used in place of more specific words that are available. To inquire into the “nature” of thinking may be as pointless as asking “What is thingness?”

MAKING A MYSTERY OF THINKING

There is no mystery about what it means to think, and nothing complicated about all the different words used to describe thoughtful activities—unless you happen to be one of the many psychologists and educators who currently have a particular interest in the topic of thinking. Many of these specialists ask—as I am asking in this book—what it means to think. But they turn their attention from what people are obviously doing when they are said to be thinking to what their brains are imagined to be doing. And many of the specialists seem to take for granted—which I do not—that distinctive brain “processes” underlie all or many of the seventy-seven “thinking” words, and other kinds of thinking as well. Many specialists also seem to take for granted—which again I do not—that all the different thinking processes that they identify (or invent) are “skills,” which can only be learned ...