This is a test

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book introduces body psychotherapy to psychologists, psychotherapists, and interested others through an attachment based, object relations, and primarily psychoanalytic and relational framework. It approaches body psychotherapy through historical, theoretical and clinical perspectives.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Touching the Relational Edge by Asaf Rolef Ben-Shahar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

HISTORICAL

You said: One day follows another; each night followed by night.

The days are upon us, you spoke in your heart.

And you shall see eves and morns attending your sight

And declare: there is no news under the sun.

Here you are, having aged, a grey elderly man

And your days are but few, and their number is dear,

You shall now know that each day is the very last

You shall now know that each day is new under the sun.

—Poems at the End of the Road, Lea Goldberg (1973, p. 152).*

Note

* All translations from Hebrew are the author’s.

CHAPTER ONE

Blanche Wittman’s breasts†: tracking the historical split between body psychotherapy and psychoanalysis

The traditions of all the dead generations weigh like a nightmare on the brain of the living.

—Karl Marx (1852, p. 15)

Nine souls

I am all but shadow

In your shadow I can rest

I am all death

In your death I might live

Eternally tied amongst your shadows, between my deaths

Stopping for a brief moment at your feet

Then I shall know comfort, in your need for me to relieve your loneliness

With your blessing

—Asaf Rolef Ben-Shahar

The birth of a split

We were not always as apprehensive of touch and body as we are today. While attention to the body and somatic processes and practices of breathwork and touch were immanent in many Eastern and non-dualistic religions and philosophies, serving as an integral part of personal growth and spiritual development, in orthodox Judaeo-Christian monotheistic traditions the body played a marginal, indirect, and almost insignificant role in personal and spiritual development (Mindell, 1982).

The seventeenth-century philosopher René Descartes, considered by many the father of modern philosophy, struggled to integrate our animalistic bodily-existence with our mental-spiritual aspects. The conclusion of his deductive philosophy, the famous cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore I am), identified the self with the cognitive, thinking self (Descartes, 1636). According to Descartes, the body was a corporeal machine and the appropriate platform to explore it was science, while the psyche belonged to the spiritual dimensions and was therefore the property of the church. While this dualistic perception created a split between body and mind, it had at the same time “liberated” the body from the trapping claws of the church in general, and the Inquisition in particular (Rolef Ben-Shahar, 2012b; Withers, 2008), allowing for real and unthreatened scientific enquiry. Additionally, the body–mind split has also gendered roots and origins, as women were considered “body”, “nature”, while men were “spiritual”, “transcendent”, superior by nature (a split that was justified by religious institutions defiling women as “body”) (Balsam, 2012; Beauvoir & Parshley, 1949).

Following our adoption of Cartesian philosophy and Newtonian physics, it had taken us Westerners centuries to catch up with the non-dualistic notion of body–mind (and self-other) unity. Medical and paramedical treatments of the body have reached inspiring sophistication and technological brilliance and, at the same time, psychological sciences and spiritual philosophies have independently reached seminal contributions and understanding regarding our psyche and spirit. However, such explorations tended to be separated from our embodied organismic experience (Capra, 1975); we still kept the divide marked by Descartes, and therefore such contributions remained limited.

Indeed, some Western philosophers and clinicians have spoken about the human being as a bodymind organism, vouching for bodymind unity, but the clinical applications of these holistic perceptions was still greatly underdeveloped. Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1953), for example, suggested that language attained meaning only in the act of speaking ideas, thus arguing that the body (and relationship) was a necessary context for language. This was the grounds for his rejecting the Cartesian subjectivist picture, which isolated “thought from action, private thought from public speech, mind from body, one mind from other minds” (Cavell, 2006, p. 64). The phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1962), whose writing was central to the development of body psychotherapy, made an even more radical claim, arguing that the body was our medium for having a world—the means with which we experienced the world, therefore the means through which we had a world. Moreover, these philosophers primarily related to the male body–mind, bodies who were actively operating in the world; however, the female body–mind was still largely denied of its integration and remained objectified (Butler, 1988; Irigaray, 1993; I. Young, 2005).

Despite these refreshing voices, the understanding that bodymind was (also) a single unity frequently got lost in the clinical settings. In the traditional psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapy, the bodies of both client and therapist tended to be absent. In this chapter I will suggest that the resistance to including the body in psychotherapeutic practice largely resulted from Freud’s (necessary) political and strategical choice to disavow the body en route to establishing psychoanalysis as a valid scientific field. Pre-psychoanalytic psychiatry was largely an attempt to alter the mind through physical interventions and laying on of hands (Kertay & Reviere, 1993). Yet it was Freud who legitimised the psychotherapeutic use of touch. His unequivocal capacity for cohesive and methodical theory, the breadth of his thinking, his clinical practice—and no less important, his charismatic personality—all these opened a door for embodied practices and touch within psychotherapy, as a methodical and organised science.

Sigmund Freud perceived himself first and foremost as a medical practitioner and a scientist. While medical practitioners could not ignore the body, as a serious scientist operating under the Cartesian–Newtonian paradigm, the knowledge that Freud acquired—and his relation to such information—was mechanistic and physiological. Accordingly, Freudian theory and practice were highly informed by bodily process. “The greatest thing that ever happened in psychiatry” wrote Wilhelm Reich (1967) about Freud, “was the discovery that the core of the neurosis was somatic” (p. 70). In The Ego and the Id, Freud (1923b) stated that the ego was “first and foremost body-ego” (p. 16). Freud further expanded on the matter: “The ego is ultimately derived from body sensations, chiefly from those springing from the surface of the body. It may thus be regarded as a mental projection of the surface of the body” (ibid.).

Many years earlier, in 1885, when he was but a young man of twenty-nine, Freud won a travelling scholarship to Paris where he studied the effects of hysteria under the supervision of the greatest neurological star of his time, Professor Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpêtrière in Paris. Freud was in awe of the magic that was revealed to him during his research with Charcot. Freud’s involvement with these maverick and innovative techniques marked the beginning of psychoanalysis and arguably the birth of Western psychotherapy.

The emergence of the forbidden body

The Parisian scene that Freud joined was full of vibrancy, charisma, and power trips. In many ways, Charcot’s hypnosis resembled traditional shamanic work more than scientific medical procedures (yet it lacked the traditional belief system that supported shamanic rituals, and gave them meaning). Freud was exposed to highly dramatised, overly technical, and very simplistic form of hypnosis. Charcot, Hippolyte Bernheim, and Josef Breuer were practising hypnosis that involved methodical passing strokes and physical pressure points, and giving suggestions in an authoritarian style. These practices were direct derivatives of the work of Franz Anton Mesmer, the father of medical hypnosis. They also heavily relied on the therapist’s charisma: the hypnotist’s authority and control over his clients were considered preconditions for therapeutic success.

The rituals and practices which were used in the hypnotic treatment of the time (and the beautiful women who were the subjects of these experimental treatments) sparked the interest and curiosity of the global medical and scientific community, but also attracted artists and celebrities who swarmed to Salpêtrière from all over the world, to witness Professor Jean-Martin Charcot delivering his therapeutic hypnotic show. Among Charcot’s students are found some of the most influential scientists and pioneers of the time, including Joseph Babinski, Pierre Janet (who was, for a while, Charcot’s laboratory head), William James, Alfred Binet (who created the first widely used intelligence test), George Gilles la Tourette (Tourette syndrome is called after his name), Paul Broca, and, of course, Sigmund Freud.

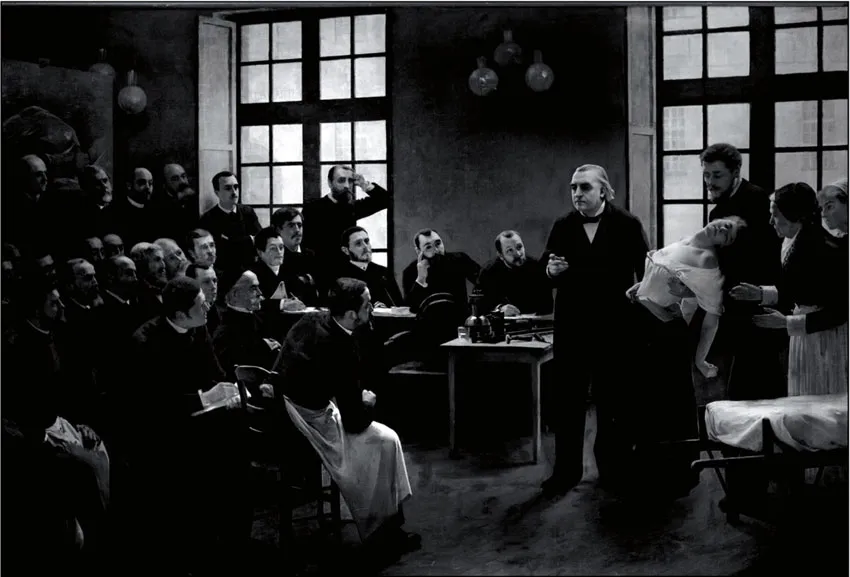

These (chauvinistic and objectifying) demonstrations of hypnosis and touch, as portrayed in Brouillet’s famous 1887 painting A Clinical Lesson with Doctor Charcot at the Salpêtrière (Figure 1) fell nothing short of a spectacular circus show. The painting, a lithograph of which was hung in Freud’s consulting room, presented the part-woman part-guineapig Blanche Marie Wittman. The histrionic pressure points required (how curious) a certain intimate exposure, thus the white and beautiful body of Wittman was publicly exposed to the doctors: a beautiful and wild hysterical woman, hypnotically collapsing into the strong arms of the kind doctor’s assistant. All the while the crowd, consisting of serious-looking male doctors, all in black, watched mesmerised. We may be left wondering whether these good doctors actually focused on the stage performance and the cutting-edge scientific discovery, or perhaps used the opportunity to stare at the wild woman’s perfect breasts (Bonduelle & Gelfand, 1999; Pérez-Álvarez & García-Montes, 2007).

Brouillet’s painting is a disturbing document reflecting the scientific, chauvinistic, and socio-political zeitgeist. It reveals the time’s attitudes towards women and regarding the body as much as it tells us about hypnosis and Charcot. At a time when touch and sexuality were forbidden, doctors were given the liberty to hypnotise their patients, undress them and caress them (for medical purposes, of course). What an inflation of excitement and fear! How hard it was to sustain a grounded ethical standing (both internal and external) faced with such drives and forces!

As a side note, it is interesting to learn that patients at the Salpêtrière were known to occasionally disappear with a swelling belly and return to the hospital after an unspoken period (Bonduelle & Gelfand, 1999). This detail may shed some new light on the case of Anna O, whose treatment was described by Freud and Breuer in Studies on Hysteria (1895d). Her treatment was terminated when erotic feelings developed between Anna O and her doctor, Breuer, climaxing in her declaring that she was pregnant with Breuer’s child. Could Breuer and Freud have become so terrified of the erotic transference also because of Salpêtrière’s abominable history?

Figure 1. A Clinical Lesson with Doctor Charcot at the Salpêtrière (Brouillet, 1887)

Examining his performance more than 120 years on, we can easily identify that the forces at play in Charcot’s demonstrations at the Salpêtrière were far greater than hypnotic suggestions. Political and gender leverage, authoritative transference dynamics, peer pressure, narcissistic saving fantasies, and erotic transference were just as influential and meaningful in creating the impact of the work as the hypnotic suggestions administered so charismatically and assuredly by Charcot. I would dare suggest that his hypnotic suggestions were actually far less influential than the other factors mentioned here.

Charcot’s hypnotic performances provided a rare legitimised peep-show, an official opportunity for voyeuristic drives and power trips, ethically approved by an authoritative figure, in a sexually oppressive and oppressed society. Imagine a room full of sexually excited men, hungry for action, in a Victorian setting. Doctors who were trained and forced to be “talking heads” alone were “forced” to witness this wild and liberated (and half-naked) woman who “willingly” submitted herself to the mercy of the powerful doctor. This painting depicted a drama that offered the spectators a particularly intimate show; in many aspects, as close as you could get to watching coitus. It is easy to see why both trance and touch were thereafter considered dangerous: the charge was too high to contain, the participants were playing with fire.

Influenced by Charcot, Freud’s early clinical work involved extensive use of hypnosis as well as some therapeutic touch. In fact, his passing and stroking techniques incorporated both touch and trance (1890, 1891). These two techniques were old-fashioned hypnotic induction techniques, involving slow passing movements over the body of the subject in a downward direction while giving suggestions to sleep, or applying touch on hypnotic pressure points. The following is a fascinating description from a letter Freud had written to his friend, otolaryngologist Wilhelm Fliess (Masson, 1985): “Yesterday Mrs K again sent for me because of cramplike pains in her chest … In her case I have invented a strange therapy of my own: I search for sensitive areas, press on them, and thus provoke fits of shaking that free her” (p. 120).

But Freud felt ambivalent about hypnosis; he became increasingly uncomfortable with its suggestive nature and the impact-laden relationship that was created between hypnotist and subject, as well as the potentially manipulative nature of such a relationship. Watching a particularly authoritative demonstration by Hippolyte Bernheim, who yelled hypnotic suggestions at his patients, Freud (1921c) reported feeling astonishment and hostility: “I said to myself that this was an evident injustice and an act of violence” (p. 89). Freud’s sensitivity to the person’s autonomy and to the therapeutic relationship was already apparent then, and indeed these touch techniques (and hypnosis techniques) were inconsistent with the therapy Freud wished to establish. Furthermore, the type of hypnosis and touch he was exposed to was procedural and mechanistic. When human touch, so rich in potential for deepening human contact, is applied mechanistically and procedurally, it can easily seem a futile, dissociating, and possibly dangerous methodology, certainly irrelevant to the psychoanalytic process.

Our theoretical and clinical positions and decisions are saturated with our biographical strengths and challenges, and indeed it seems that Freud’s primary reason for abandoning hypnosis and touch was more complex than the professional account presented above. In An Autobiographical Study, Freud (1925d) narrated the following incident:

And one day I had an experience which showed me in the crudest light what I had long suspected. It related to one of my most acquiescent patients, with whom hypnotism had enabled me to bring about the most marvellous results, and whom I was engaged in relieving of her suffering by tracing back her attacks of pain to their origin. As she woke up on one occasion, she threw her arms round my neck. The unexpected entrance of a servant relieved us from painful discussions but from that time onwards there was a tacit understanding between us that the hypnotic treatment should be discontinued. (p. 27, my italics)

Note that this reported event was so unsettling for both parties that Freud deemed it to remain unspoken! This incident, which led Freud to abandon hypnosis around 1896, was an excellent example of the power of transference (and countertransference), which may arise in psychotherapy. Realising the complexity of the therapeutic relationship, Freud no longer thought that real trauma was always at the base of neurosis and concluded that many of his patients unconsciously fabricated their abuse stories in order to satisfy the desire of the hypnotist. He therefore found the hypnotic work potentially masking and confusing the analytic process.

Melvin Gravitz (2004) suggested that it was Freud’s discomfort with the degree of transference, particularly erotic transference that pushed him to abandon hypnosis. Thus, the very phenomenon that was to later become the central axis of psychoanalytic work—transference dynamics—was at first rejected by Freud, considered as an obstacle to the therapeutic process, and moreover deemed taboo.

After he ceased using hypnosis, Freud continued for a short while to work with the pressure technique, which was based on the hypnotic protocol. He believed that the pressure technique assisted the patient to reach an energetic discharge (catharsis) quicker, thus freeing pent-up emotional and bodily energy (Hinshelwood, 2002). However, within a short while Freud deserted cathartic work altogether, forbidding the psychoanalytic use of touch and hypnosis thereafter.

Psychoanalytic technique was at first affective and abreactive, incorporating techniques that actively sought to encourage cathartic expression for emotional and bodily experiences. In order to establish and deepen the psychoanalytic relationship, Freud shifted the focus of the psychoanalytic pr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- PREFACE

- PREFACE

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: HISTORICAL

- PART II: THEORETICAL

- PART III: CLINICAL

- SUMMARY The relational matrix—a suggested model

- APPENDIX The relational approach

- GLOSSARY

- REFERENCES

- INDEX