This is a test

- 284 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

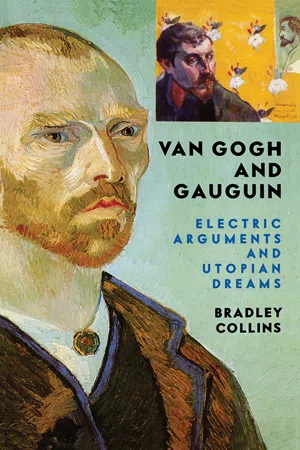

Although Vincent van Gogh's and Paul Gauguin's artistic collaboration in the south of France lasted no more than two months, their stormy relationship has continued to fascinate art historians, biographers, and psychoanalysts as well as film-makers and the general public. Van Gogh and Gauguin explores the artists' intertwined lives from a psychoana

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Van Gogh And Gauguin by Bradley Collins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

__ 1 __

Van Gogh

Zundert to Paris

I

Although art historians have spent decades demystifying van Gogh’s legend, they have done little to diminish his vast popularity. Auction prices still soar, visitors still overpopulate van Gogh exhibitions, and The Starry Night remains ubiquitous on dormitory and kitchen walls. So complete is van Gogh’s global apotheosis that Japanese tourists now make pilgrimages to Auvers to sprinkle their relatives’ ashes on his grave. What accounts for the endless appeal of the van Gogh myth? It has at least two deep and powerful sources. At the most primitive level, it provides a satisfying and nearly universal revenge fantasy disguised as the story of heroic sacrifice to art. Anyone who has ever felt isolated and unappreciated can identify with van Gogh and hope not only for a spectacular redemption but also to put critics and doubting relatives to shame. At the same time, the myth offers an alluringly simplistic conception of great art as the product, not of particular historical circumstances and the artist’s painstaking calculations, but of the naive and spontaneous outpourings of a mad, holy fool. The gaping discrepancy between van Gogh’s long-suffering life and his remarkable posthumous fame remains a great and undeniable historical irony. But the notion that he was an artistic idiot savant is quickly dispelled by even the most glancing examination of the artist’s letters. It also must be dropped after acquainting oneself with the rudimentary facts of van Gogh’s family background, upbringing, and early adulthood.

The image of van Gogh as a disturbed and forsaken artist is so strong that one easily reads it back into his childhood and adolescence. But if van Gogh had died at age twenty, no one would have connected him with failure or mental illness. Instead he would have been remembered by those close to him as a competent and dutiful son with a promising career in the family art-dealing business. He was, in fact, poised to surpass his father and to come closer to living up to the much-esteemed van Gogh name.

The van Goghs were an old and distinguished Dutch family who could trace their lineage in Holland back to the sixteenth century. Among Vincent’s five uncles, one reached the highest rank of vice-admiral in the Navy and three others prospered as successful art dealers. Van Gogh’s grandfather, also named Vincent, had attained an equally illustrious status as an intellectually accomplished Protestant minister. The comparatively modest achievements of the artist’s father, Theodorus, proved the exception, not the rule. Although Theodorus was the only one of grandfather Vincent’s six sons to follow him into the ministry, he faltered as a preacher and could obtain only modest positions in provincial churches. It was for this reason that Theodorus and his new wife, Anna, found themselves in Groot Zundert, a small town near the Belgian border. Vincent was born a few years after their arrival.

Van Gogh enjoyed a relatively uneventful childhood save for the birth of five siblings (three by the time he was six and two more by his fourteenth year) and his attendance at two different boarding schools. In rural Zundert he took long walks in the Brabant countryside and developed a naturalist’s love of animals and plants. At his two boarding schools, he excelled at his studies and laid down the foundation for his lifelong facility in French and English. The family’s decision to apprentice him at sixteen to Uncle Vincent’s art gallery in The Hague was far from a nepotistic last resort. Uncle Vincent, called “Cent,” had transformed an art supply store into a prestigious art gallery and had become a senior partner in Goupil et Cie., one of the largest art-dealing firms in Europe. Vincent had no better opportunity for advancement than working at The Hague branch of Goupil’s. And it was a testament to Vincent’s abilities that the childless “Uncle Cent” took a paternal interest in him and arranged for his position as Goupil’s youngest employee.

Vincent’s duties progressed from record keeping and correspondence chores in the back office to dealing, if only in a subordinate way, with clients. This confronts us with the nearly unthinkable image of the “socially competent” Vincent. But such was the case at this stage in his life. The same man whose eccentricity would one day make young girls scream in fright dressed appropriately and charmed customers with his enthusiasm for art. Vincent also ingratiated himself with the local artists of The Hague School and earned his colleagues’ respect. Although his status as Uncle Cent’s nephew and protégé must have smoothed his way, Vincent appears to have been genuinely dedicated and effective at Goupil’s. His boss, Tersteeg, sent home glowing reports and after four years at The Hague he was promoted to the London branch.

By the time the twenty-year-old van Gogh settled in London, he possessed an exceptional knowledge of European art. Not only had he seen the contemporary paintings in Goupil’s stock, but he had also exhaustively versed himself in the Golden Age of northern art by visiting museums in The Hague, Amsterdam, and Brussels. Added to this was his sojourn in Paris on his way to London. In Paris he thoroughly explored Goupil’s three branches and other collections as well as the Louvre. The museums and exhibitions in London only deepened his exposure to pictures. Of course, his immersion in images extended beyond original paintings and drawings. He would have seen thousands of reproductions in the course of his work. Goupil’s specialized in selling both engravings and photographic reproductions (Vincent, in fact, had been in charge of the photographic sales at The Hague). Although Vincent had not toured Italy, this constituted one of the few lacunae in his visual education. Nor were van Gogh’s cultural interests limited to art. He voraciously read novels, poetry, and historical works in three languages (Dutch, French and English). After only a few months in London, he could already quote Keats in his letters. So much for van Gogh as a “primitive.” The rawness that he later permitted in his appearance and cultivated in his art disguised a sensibility of extreme sophistication.

Vincent’s first year in London took him to a great height of euphoria from which he plunged precipitously. He was exhilarated by the city, his work continued to engage him, and, most important, he fell in love. He became smitten with his landlady’s daughter, Eugénie Loyer. For months van Gogh quietly nursed his affections and assumed, on no basis whatsoever, that Eugénie reciprocated his passion. This irrational belief grew so firm that when he finally spoke to her of his romantic feelings he skipped all preliminaries and simply proposed marriage. The shocked Eugénie not only emphatically rejected the offer but disclosed that she was already secretly engaged to a previous boarder. Eugénie’s response entirely derailed Vincent. He became distracted at Goupil’s and sought consolation for his deep depression in religious fervor and manic Bible study. In the next year and a half Uncle Cent and the other partners shuttled Vincent back and forth between Goupil’s Paris and London branches in an attempt to jolt him out of his despair. Nothing worked and Goupil’s finally dismissed him in January of 1876. From this point onward Vincent would never again succeed at a conventional occupation and would always remain a source of embarrassment to his family.

Why was this romantic disappointment so catastrophic for van Gogh? Why couldn’t he shake it off as so many young men do? A psychoanalytic explanation finds the answer, not surprisingly, in van Gogh’s childhood. A startling fact of the artist’s infancy is that he was preceded by a first, stillborn Vincent, who died exactly a year to the day before his own birth. The death of a first child deals a severe blow to any mother, but this loss would have been particularly harsh for the thirty-three-year-old Anna, who married late and eagerly wished for a family. The official mourning period extended beyond Vincent’s birth and may have been more than a formality in this case. Vincent would have found himself with a mother consumed by her grief and unable to lavish undivided attention on him. Making matters worse, Vincent would continue to suffer displacement in his mother’s affections first by his sister, Anna, born when he was two, and then by Theo’s birth when he was four. These successive disappointments during the crucial first years of infancy may have formed a deep, unconscious reservoir of depression. Eugénie’s rejection would have tapped into this reservoir and opened the floodgates.

That an unavailable mother lived on powerfully in van Gogh’s unconscious is dramatically underscored by the type of woman to whom he invariably attached himself. Indeed, one would be hard put to find a more insistent case of repetition compulsion (that is, the compulsion to return to traumatic or painful situations). Eugénie was only the first in a line of preoccupied women on whom van Gogh became fixated. Eugénie had lost her father in her childhood and now had her secret engagement to the boarder to fill her thoughts. A surviving photograph reveals her as a forbiddingly severe latter-day replacement for the once-distant Anna. Kee Vos-Stricker, who had lost both an infant son and her husband, would eventually succeed Eugénie in this role of unattainable love object. Yet even at the early stages of Vincent’s infatuation with Eugénie he had already come across an image of a mourning woman that held him in thrall. One of his favorite authors, Jules Michelet, had written evocatively of a portrait in the Louvre, then attributed to Philippe de Champaigne, that depicted a woman dressed in black mourning clothes. Vincent hung an engraving of the painting on his wall and quoted Michelet’s words in a letter to friends in The Hague:

… who took my heart, so candid, so honest, sufficiently intelligent, yet simple, without the cunning to extricate herself from the ruses of the world. This woman has remained in my mind for thirty years, persistently coming back to me, making me say: “But what was she called? What has happened to her? Has she known some happiness? And how has she overcome the difficulties of the world?”1

When one views the actual portrait, the sitter appears as an extremely unlikely source of devotion for a twenty-year-old man. She is markedly dour, middle-aged, and plain. It is resounding evidence—almost too good to be true—that Vincent’s mother stood behind his obsession with mourning women. And Michelet’s account of a female figure who “has remained in my mind … persistently coming back to me,” strikingly mirrors the stubborn presence of the grieving Anna in Vincent’s unconscious.

If we can trace the roots of van Gogh’s attraction to Eugénie and his subsequent devastation to his childhood, we can also see his means of recuperation as a legacy of his early years. Vincent embraced Theodorus’s world of religious piety just as he may have turned as a child from rageful ambivalence toward his indifferent mother to yearning for his father. Vincent’s letters to his brother Theo disclose the growing momentum of his religious mania. It starts with occasional quotations from the New Testament a few months after his failed proposal and moves on to three separate exhortations to Theo to destroy his books and read nothing but the Bible—a remarkable proscription from the bibliophilie Vincent. The intense spiritual preoccupations reach a crescendo with a multipage letter, written almost a year after his dismissal from Goupil’s, that consists of a relentless and unorganized flow of citations from Scripture, sermonizing admonitions, and outpourings of faith. The letter contrasts so greatly with Vincent’s usual cheeriness, descriptions of paintings and scenery, and warm solicitousness toward his brother and other family members that it must have disturbed Theo.

Vincent’s second job after leaving Goupil’s gave him an outlet for his feverish religiosity. A Methodist minister, Reverend Thomas Slade-Jones, hired him as an assistant and as a teacher in his day school in Isleworth. Jones encouraged van Gogh’s ambition to preach the gospel and even arranged for him to give his first sermon in a Wesleyan chapel in Richmond. The text, which Vincent transcribed for Theo, unifies many of his concerns and offers both intentional and unintentional glimpses into his psyche. He begins with a quote from Psalm 119—“I am a stranger on the earth.”2 This passage enunciates the sermon’s theme of man as a wayfarer passing through his mortal existence but must also have been an expression of Vincent’s own sense of isolation from his former colleagues and friends. He ends with an elaborately described recollection, which appears more like a fantasy than an actual memory, of a “very beautiful picture.” It is an allegorical painting in which a pilgrim seeks knowledge about the journey of life from “a woman, or figure in black, that makes one think of St. Paul’s word: As being sorrowful yet always rejoicing.” Here, Vincent not only brings together his twin loves of religion and art but also presents two of the strongest currents in his inner world—the image of the mourning woman and the attitude of being “sorrowful yet always rejoicing” (a phrase that recurs dozens of times in his letters of this period). The image and the phrase are, of course, intertwined. The “lady in black”—his grieving mother—creates sorrow that must always be met with rejoicing, just as Vincent must always answer his depression with manic activity.

Vincent’s religious utterances also reveal both a symbolic and explicit love of his father. In the letter to Theo mentioned above, in which Vincent becomes so frenzied that he seems to write in tongues, he recalls Theodorus’s visit to his boarding school:

… I was standing in the corner of the playground when someone came and told me that a man was there, asking for me; I knew who it was, and a moment later I fell on Father’s neck. What I felt then, could not it have been “because ye are sons, God hath sent forth the Spirit of his Son into your hearts, crying, Abba, Father”? It was a moment in which we both felt we had a Father in heaven; for Father too looked upward, and in his heart there was a greater voice than mine, crying, “Abba, Father.”3

This passage provides one of the best examples of the nearly indistinguishable nature for Vincent of his own “father” and his “Father” in heaven. Such outpourings of filial piety are accompanied in the letters by an impassioned idealization of Theodorus as well as an identification with his calling. Van Gogh’s father is “more beautiful than the sea” and “enrich[es] our lives with moments and periods of higher life and higher feeling.”4 His sermons are “beautiful,” and a day spent with him is “glorious.”5 Theodorus even takes his place in Vincent’s pantheon alongside exalted figures such as Jules Breton, Millet, and Rembrandt. These artists, Vincent wrote, resembl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 Van Gogh: Zundert to Paris

- 2 Gauguin: Lima to Pont-Aven

- 3 Van Gogh in Paris and First Encounters with Gauguin

- 4 Jean Valjean and the Buddhist Monk: Van Gogh in Anticipation of Gauguin

- 5 Electric Arguments: “Le Bon Vincent” and “Le Grièche Gauguin”

- 6 Aftermath

- Chronology

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index