![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A Transactional Analysis of obsession: integrating diverse concepts and methods

Richard G. Erskine

“

Worry, worry, worry. That’s all I do,” despaired my first client on Monday morning. She had been worrying for most of her life and was convinced that she would never stop worrying. She was like many of the clients I was scheduled to work with that week: habitual worrying and repetitive fantasising absorbed much of their mental activity and interfered with their capacity for spontaneity, intimacy, and living joyfully in the present. I knew that I would be attending, at least some of the time, to aspects of obsession with several of my clients throughout the week no matter what other issues we might be addressing.

Psychological problems such as repetitive fantasising, habitual worrying, and obsessing appear to be on the rise over the last few years among people seeking psychotherapy. These types of problems seem to cut across many psychological diagnoses and include some clients who would not necessarily receive a confirmed DSM-IV or DSM-V diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 1994, 2013). Obsessing and habitual worrying may be among the major treatment issues of our time, reflective of the lifestyle and career pressures, developmental experiences, deficits in interpersonal relationships, and issues of life script (McAdams & Pals, 2006). Obsessing, repetitive fantasising, and habitual worrying are so common, and often so private, that these issues may go unreported in therapy. When addressed in psychotherapy such rumination may receive only cursory attention or may not seem pertinent to issues of life script (Berne, 1972).

The psychotherapy of obsessing and repetitive fantasising was briefly addressed through clinical case examples in a few previous Transactional Analysis Journal articles (Allen, 2003; Erskine, 2001, 2003, 2008; Nolan, 2008; Novellino, 2006; Schaeffer, 2009). Yet the Transactional Analysis psychotherapy of habitual worrying, repetitive fantasising, and obsessing has not received adequate attention in the clinical literature. Neither theoretical conceptualisations for understanding these problems nor a description of various methods have been published. This chapter fills that deficit by presenting a six point treatment perspective for the psychotherapy of obsessing, habitual worrying, and repetitive fantasising.

This chapter is the outcome of a qualitative multiple case study which has identified six major facets of psychotherapy that integrate both an understanding of the psychological dynamics of obsessing, repetitive fantasising, and habitual worrying and an integration of psychotherapy methods that are effective in maintaining permanent change to such dynamics (Erskine et al., 2001). In describing human personality characteristics, such as obsessing and worrying, Kluckholm & Murray (1953) wrote that every person is like all other persons, like some other persons, and like no other person, therefore we can often take clinical data from a few individuals and effectively generalise our knowledge to a larger population provided that we constantly monitor and also inquire into the unique, phenomenological experience of each client. This chapter is a compilation of the Transactional Analysis methods that were significantly effective with some clients and suggest that these methods may be equally effective with a wide variety of clients in Transactional Analysis psychotherapy.

The Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual describes obsessions as relatively common symptoms wherein obsession is an attempt to disavow affect and engage in intellectualisation rather than to feel emotions, especially among more cerebral and perfectionistic individuals. Obsessing, habitual worrying, and repetitive fantasising often indicate a person’s reluctance to feel emotions associated with either being “overwhelmed” or “out of control” (PDM Task Force, 2006, p. 58). Freud (1913i) described obsession and worry as originating in early child–parent dyadic struggles. He related the stubborn, punctilious, and hoarding tendencies of the adult with obsessional neurosis to childhood battles over toilet training. However, current client narratives indicate the significance of power struggles between child and parents around rigid standards of behaviour, eating, school work, sexuality, and general obedience as the childhood conflicts that underlie many obsessions and repetitive worries. In essence, growing up with relational discord is central for people who engage in habitual worrying, repetitive fantasies, and obsession.

Many such clients report that their childhood attempts at expressions of subjectivity and affect were labelled as bad or immature or not rational. As a result, many clients are absorbed with repetitive fantasies or reoccurring obsessions; they are out of touch with their emotions and are more preoccupied with self-definition or making an impact than interpersonal relationships. They appear to be internally compelled by their rumination and often fear their own feelings and thoughts, especially if they are aggressive. “Living machines” was the term used by William Reich in Character Analysis (1933) to describe such obsessive people. Obsessive thoughts are an attempt to counteract phenomenological experience that is feared to be overwhelming. As a result, such clients have trouble relaxing, joking, being intimate, and living in the now. Obsessive people are chronically “in their heads”: thinking, reasoning, judging, doubting (Fisher & Greenberg, 1985; Salzman, 1980; Shapiro, 1965 as cited in PDM Task Force, 2006).

Transactional Analysis in psychotherapy

The treatments identified as empirically supported therapies are behavioural or cognitive-behavioural in nature, reflecting the greater formal or empirical research activity of psychotherapy outcome researchers of that orientation (Chambless, 2005). However, addressing and resolving the clients’ underlying loneliness, resolving unconscious longing for meaningful relationship, appreciating and reorienting the homeostatic functions of obsessing, dissolving archaic script beliefs and introjections, and enriching their emotional lives requires considerable time— time with an involved psychotherapist who is willing to help them explore emotional memories and express phenomenological experiences that they otherwise spend an inordinate amount of time and energy to avoid.

An in-depth psychotherapy of this nature is a profoundly co-creative process that does not lend itself to empirical research (Summers & Tudor, 2000; Tudor, 2011b). As of the time of writing there are no outcome studies of the use of Transactional Analysis in the psychotherapy of obsession, habitual worry, or repetitive fantasising. Yet clinical discussions among experienced colleagues have clarified several therapeutic facets that seem to be effective with a number of clients.

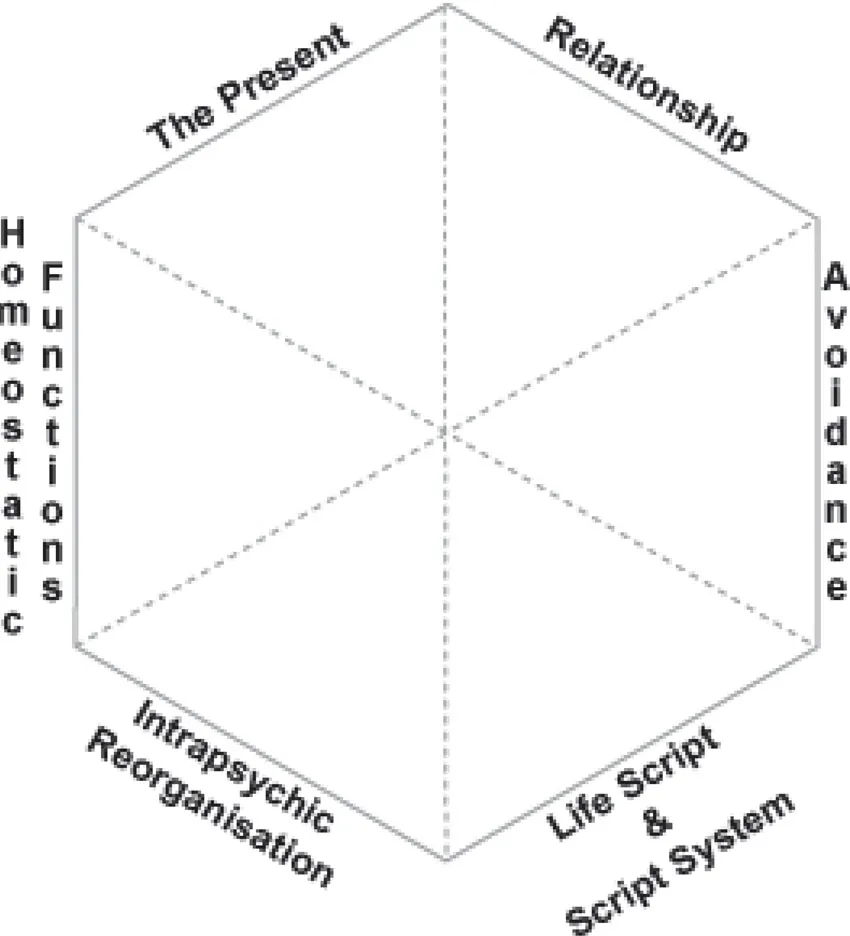

As an overview I want to briefly describe how I organise the psychotherapy of obsession along six distinct facets. I use the word “facets” rather than “stages” because the psychotherapy is not linear. Our therapeutic dialogues cycle from one facet to another in response to what is emerging in the intersubjective process. The client and I may address one or two of these facets in a particular session or series of sessions, then move on to another facet for a while, eventually returning to a previous facet. In due course we interweave all six facets to form a comprehensive psychotherapy. For the reader interested in further case examples or an elaboration of the theoretical concepts mentioned in this chapter I will reference several publications that will cover the various ideas more thoroughly. A careful reading of these primary sources may illuminate the comprehensiveness of Transactional Analysis in contemporary psychotherapy.

Figure 1. Integration of six therapeutic facets.

Relationship: The therapeutic relationship is central no matter what methods or other perspectives we may use. My clinical experience has shown that clients who are habitually worrying are unconsciously longing for a meaningful relationship. They are lonely, yet they often carry a fear of repeating the disruptions and failures of past relationships. As a result they avoid full interpersonal contact and fill the emptiness with internal dialogue, fantasy, or anticipations.

In this facet the therapeutic focus is on establishing and maintaining the client’s sense of relational security, self-definition, and interpersonal agency and efficacy (Erskine & Trautmann, 1996; Erskine, 2003a). This is accomplished, in part, by the psychotherapist’s transactions of respect, acceptance, kindness, clarity, and patience. At the same time, the therapeutic focus is on inquiring about the client’s current relational needs, his unrequited archaic needs, how he coped with previous relational disruptions, and the unconscious story encoded in the emotional transference of previous relational experiences—transference both with the psychotherapist and with others (Erskine, 1991, 2010a; R. Little, 2011a; Moiso, 1985; Novellino, 1984).

Avoidance: The second facet involves discovering what is being avoided through the repetitive fantasising or obsessing. The anxiety associated with obsessing or fantasising is often about avoiding one’s feelings, thoughts, and/or memories (Erskine, 2001, 2003a, 2008). This concept is an elaboration of the Transactional Analysis notion of “rackets” as a substitute feeling, a distraction from what one may authentically experience (such as shame, despair, or loneliness) if there was no interfering alternative or substitute (Berne, 1972; English, 1971, 1972).

I may ask, “What would you be feeling if you were not feeling the fear in your fantasy?” or “What would you be experiencing right now if you were not distracted by what you are saying?” Some clients are clear in answering these questions and others are initially confused by them. These are the types of questions to which I often return throughout the psychotherapy. The client’s answers are often surprising and lead us to other facets of the psychotherapy, to new levels of discovery and awareness.

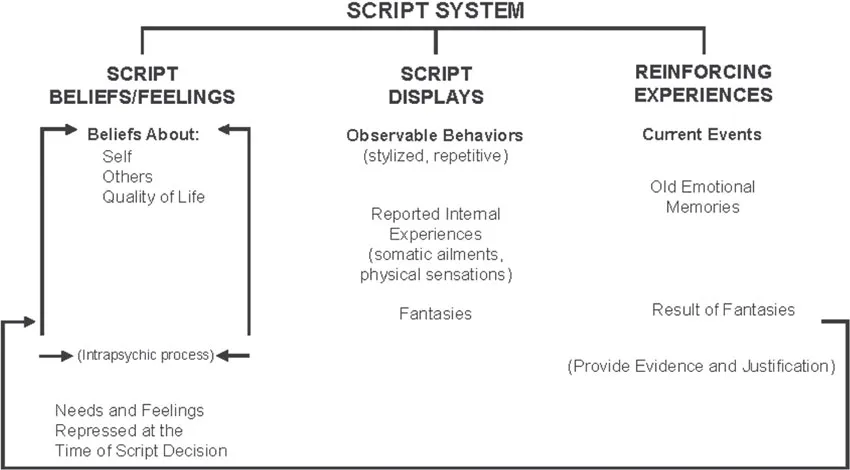

Life script and the script system: The third facet requires uncovering and dissolving the client’s life script. Life scripts are a creative and accommodating strategy to manage the psychological stress, or even the shock, of repetitive, problematic relationships (Erskine, 2010b). I usually work with the script system (previously called racket system) to help the client identify his accommodating strategies—the core beliefs about self, others, and the quality of life. Script system work often begins with identifying the behaviours or fantasies that generate reinforcing memories that, in turn, maintain the script beliefs (Erskine, 2015; Erskine & Zalcman, 1979; Gildebrand & Shivanath, 2011; O’Reilly-Knapp & Erskine, 2010). Life scripts keep people within a closed system composed of archaic feelings and needs, childhood conclusions and decisions, egocentric fantasies, and related body-tensions. This closed system interrupts both internal sensitivity to current relational needs and the capacity for full interpersonal contact (Erskine, 2010b). The therapeutic resolution of a life script involves an affective/cognitive reorganisation of core beliefs about self-in-relationship. Such an intrapsychic reorganisation both precedes and maintains changes in behaviour and fantasy.

Figure 2. The script system.

Intrapsychic reorganisation: The fourth facet of the psychotherapy encompasses working with the client’s archaic experiences via a developmental perspective, therapeutic inference, and a secure relationship that allows the client to have a supported and restorative regression. The therapeutic focus is on the client’s processes of archaic self-stabilisation and self-protection, his restrictions in physiology and affect, as well as decoding the client’s enactments of implicit and procedural memories. This is where the therapy is concentrated on the feelings, needs, and reactions of a young child and the qualities of a reparative relationship that the client requires. This work may include:

• Deconfusion of the Child ego states (Berne, 1961; B. D. Clark, 1991; Clarkson & Fish, 1988; Cornell & Olio, 1992; Erskine, Moursund, & Trautmann, 1999; Hargaden & Sills, 2001, 2002; R. Little, 2005; Moursund & Erskine, 2003; Novellino, 1990; Stuthridge, 2006, 2012).

• Redecision work (Allen, 2010; Campos, 1995; Goulding & Goulding, 1979; Masse, 1995; McNeel, 1977; Thunnissen, 2010).

• Deep emotional/physiological expression and intrapsychic reorganisation referred to as “disconnecting rubber bands” (Childs-Gowell, 2000; Erskine, 1974; Erskine & Moursund, 1988; R. Little, 2001).

• Psychotherapy of the Parent ego states (Dashiell, 1978; Erskine, 2003b; Erskine & Trautmann, 2003; R. Little, 2006; McNeel, 1976; Mellor & Andrewartha, 1980).

• Working with the retroflections and inhibitions in the body (Cassius, 1977, 1980; Child-Gowell & Kinnaman, 1978; Cornell, 1975, 1997; Cornell & Landaiche, 2007; Erskine, 2014b; Hawkes, 2003; Ligabue, 1991; Uma Priya, 2007; Waldekranz-Piselli, 1999).

Whether the psychotherapy is with a Child or Parent ego state, the aim of such intrapsychic work is to provide a reorganisation of sub-symbolic experience and archaic homeostatic functions that interfere with the client’s current life (Erskine, 2015). In-depth psychotherapy, when done according to the client’s needs and rhythm, facilitates a physiological/ affective reorganisaation that involves a neurological realignment of the amygdala-hippocampus-adrenal system of a nuclear sense of self (Cozolino, 2006; Damasio, 1999). For a further elaboration on psychotherapy with the Child ego states please see Chapter Seven by Erskine and Mauriz-Etxabe in this book.

Homeostatic functions: The fifth facet, homeostatic functions, contributes an understanding and appreciation of affect and physiological equilibrium—a homeostasis that maintains external behaviours as well as internal processes such as script beliefs, habitual worrying, or repetitive fantasies, and emotionally laden habits. Obsessing, habitual worrying, and repetitive fantasising are each creative strategies to maintain an emotional balance and to manage the psychological stress, or even the shock, of repetitive, problematic relationships. These accommodating strategies are a desperate attempt at either self-reparation or self-stabilisation.

There are several possible psychological functions. Some examples include self-regulation, compensation, self-protection, orientation, and insurance against shock of further disruptions in relationship. The repetitive behavioural patterns and internal rumination may also function to maintain a sense of integrity—a continuity of the struggle to define and value one’s self within a variety of relationships. These examples of psychological functions reflect the person’s outmoded attempts to generate and maintain a sense of psychological equilibrium following affectively overwhelming disruptions in significant relationships. They are homeostatic strategies that provide predictability, identity, consistency, and stability (Erskine, 2015; Erskine, Moursund, & Trautmann, 1999).

A frequently used way to stop obsessing and worrying is to say to one’s self, “Stop!” Such an exhortation may work temporarily; however, a more effective way to permanently stop obsessing is to identify and maintain awareness of the archaic homeostatic functions that perpetuate the obsession and to transform those archaic functions into mature functions.

Underpinning any emotional or behavioural change, I find it essential to work collaboratively with clients in uncovering the various archaic functions of obsessing and habitual worrying and then to transpose those archaic functions to mature forms of self-regulation and self-enhancement (Kohut, 1977; Wolf, 1988).

The present: The sixth facet focuses on helping the obsessing client live in the present moment rather than ruminating about the past or fearfully anticipating the future. Habitual worries and fantasies or repetitive uncomfortable memories are each an attempt to influence either the past or the future; they serve as a distraction from living in the now. Paradoxically these habitual worries and fantasies are a sign of hopefulness in that they serve as an insurance against emotional shock if something were to go wrong.

Awareness of what is currently occurring both internally and externally is a central point in the psychotherapy of obsessing. I often have the client look back over time and examine the wasted energy and lost opportunities for enjoyment, spontaneity, creativity, or adventure that may have occurred if he were not obsessing. In this facet of therapy we focus on fostering the client’s sense of “OK-ness” through discovering and maintaining self-awareness, accepting the uncertainties of life, living in the “now”, and perhaps developing a sense of universal connectedness or spirituality. As an alternative to habitual worrying I may work with the client to develop a motto such as, “No matter what the outcome, I will learn and grow from the experience” (Erskine, 1980). A principal focus in the psychotherapy of obsession is helping the client to develop present centred mindfulness (Allen, 2011; Trautmann, 2003; Verney, 2009; Žvelc, Černetič, & Košak, 2011).

An elaborative case

Bobby’s wife had insisted that he seek psychotherapy because his obsessive worries and behaviours were interfering with both their marriage and the relationship with his two young children. He was not certain that he “needed psychotherapy” or that he even had “a problem”. “I only worry a bit,” he said. His body squirmed and tensed as he complained about his wife not understanding him, how hard he worked, and how some of the other men at work were “not taking responsibility”. Although he expressed some concern about his marriage he was primarily worried about his firm’s success and his future career. My reaction in this first session, and during the next few, was to relax and listen—to listen with a sensitive ear, not only to his current distress, but to the stories he was unconsciously telling, to the interpersonal conflicts he had endured, to how he had coped, and for his unarticulated developmen...