Extracts From Case History Illustrating The Boy’s Oedipus Development

The material on which I shall draw to illustrate my views about the boy’s Oedipus development is taken from the analysis of a boy of ten. His parents felt impelled to seek help for him since some of his symptoms had developed to such an extent that it became impossible for him to attend school. He was very much afraid of children and because of this fear he more and more avoided going out by himself. Moreover, for some years a progressive inhibition of his faculties and interests caused great concern to his parents. In addition to these symptoms, which prevented him from attending school, he was excessively preoccupied with his health and was frequently subject to depressed moods. These difficulties showed themselves in his appearance, for he looked very worried and unhappy. At times, however — and this became striking during analytic sessions—his depression lifted and then sudden life and sparkle came into his eyes and transformed his face completely.

Richard was in many ways a precocious and gifted child. He was very musical and showed this already at an early age. He had a pronounced love of nature, but only of nature in its pleasant aspects. His artistic gifts showed, for instance, in the ways in which he chose his words and in a feeling for the dramatic which enlivened his conversation. He could not get on with children and was at his best in adult company, particularly in the company of women. He tried to impress them by his conversational gifts and to ingratiate himself with them in a rather precocious way.

Richard’s suckling period had been short and unsatisfactory. He had been a delicate infant and had suffered from colds and illnesses from infancy onwards. He had undergone two operations (circumcision and tonsillectomy) between his third and sixth year. The family lived in modest but not uncomfortable circumstances. The atmosphere in the home was not altogether happy. There was a certain lack of warmth and of common interests between his parents, though no open trouble. Richard was the second of two children, his brother being a few years his senior. His mother, though not ill in a clinical sense, was a depressive type. She was very worried about any illness in Richard, and there was no doubt that her attitude had contributed to his hypochondriacal fears. Her relation to Richard was in some ways not satisfactory; while his elder brother was a great success at school and absorbed most of the mother’s capacity for love, Richard was rather a disappointment to her. Though he was devoted to her, he was an extremely difficult child to deal with. He had no interests and hobbies to occupy him. He was over-anxious and over-affectionate towards his mother and clung to her in a persistent and exhausting way.

His mother lavished much care on him and in some ways pampered him, but she had no real appreciation of the less obvious sides of his character, such as a great inherent capacity for love and kindness. She failed to understand that the child loved her very much, and she had little confidence in his future development. At the same time she was on the whole patient in dealing with him; for instance she did not attempt to press the company of other children on him or to force him to attend school.

Richard’s father was fond of him and very kind to him, but he seemed to leave the responsibility for the boy’s upbringing predominantly to his mother. As the analysis showed, Richard felt that his father was too forbearing with him and exerted his authority in the family circle too little. His elder brother was on the whole friendly and patient with Richard, but the two boys had little in common.

The outbreak of the war had greatly increased Richard’s difficulties. He was evacuated with his mother, and moved with her for the purpose of his analysis to the small town where I was staying at the time, while his brother was sent away with his school. Parting from his home upset Richard a good deal. Moreover the war stirred all his anxieties, and he was particularly frightened of air-raids and bombs. He followed the news closely and took a great interest in the changes in the war situation, and this preoccupation came up again and again during the course of the analysis.

Though there were difficulties in the family situation—as well as serious difficulties in Richard’s early history—in my view the severity of his illness could not be explained by those circumstances alone. As in every case, we have to take into consideration the internal processes resulting from, and interacting with, constitutional as well as environmental factors; but I am unable to deal here in detail with the interaction of all these factors. I shall restrict myself to showing the influence of certain early anxieties on genital development.

The analysis took place in a small town some distance from London, in a house whose owners were away at the time. It was not the kind of playroom I should have chosen, since I was unable to remove a number of books, pictures, maps, etc. Richard had a particular, almost personal relation to this room and to the house, which he identified with me. For instance, he often spoke affectionately about it and to it, said good-bye to it before leaving at the end of an hour, and sometimes took great care in arranging the furniture in a way which he felt would make the room ‘happy’.

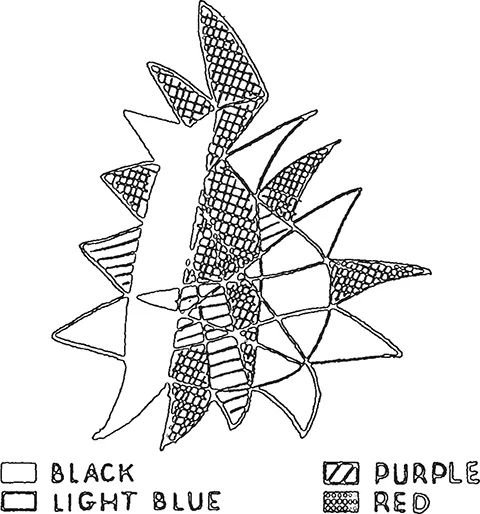

In the course of the analysis Richard produced a series of drawings.1 One of the first things he drew was a starfish hovering near a plant under water, and he explained to me that it was a hungry baby which wanted to eat the plant. An octopus, much bigger than the starfish and with a human face, entered into his drawings a day or two later. This octopus represented his father and his father’s genital in their dangerous aspects and was later unconsciously equated with the ‘monster’ which we shall presently encounter in the material. The starfish shape soon led to a pattern drawing made up of different coloured sections. The four main colours in this type of drawing—black, blue, purple and red—symbolized his father, mother, brother and himself respectively. In one of the first drawings in which these four colours were used he introduced black and red by marching the pencils towards the drawing with accompanying noises. He explained that black was his father, and accompanied the movement of the pencil by imitating the sound of marching soldiers. Red came next, and Richard said it was himself and sang a cheerful tune as he moved up the pencil. When colouring the blue sections he said this was his mother, and when filling in the purple sections he said his brother was nice and was helping him.

The pattern represented an empire, the different sections standing for different countries. It is significant that his interest in the events of the war played an important part in his associations. He often looked up on the map the countries which Hitler had subjugated, and the connection between the countries on the map and his own empire drawings was evident. The empire drawings represented his mother, who was being invaded and attacked. His father usually appeared as the enemy; Richard and his brother figured in the drawings in various rôles, sometimes as allies of his mother, sometimes as allies of his father.

These pattern drawings, though superficially similar, varied greatly in detail—in fact we never had two exactly alike. The way he made these drawings, or for that matter most of his drawings, was significant. He did not start out with any deliberate plan and was often surprised to see the finished picture.

He used various sorts of play material; for instance the pencils and crayons with which he made his drawings also figured in his play as people. In addition he brought his own set of toy ships, two of which always stood for his parents, while the other ships appeared in varying rôles.

For purposes of exposition I have restricted my selection of material to a few instances, mainly drawn from six analytic hours. In these hours—partly owing to external circumstances which I shall discuss later—certain anxieties had temporarily come more strongly to the fore. They were diminished by interpretation, and the resulting changes threw light on the influence of early anxieties on genital development. These changes, which were only a step towards fuller genitality and stability, had already been foreshadowed earlier on in Richard’s analysis.

With regard to the interpretations adduced in this paper, it goes without saying that I have selected those which were most relevant to my subject matter. I shall make clear which interpretations were given by the patient himself. In addition to interpretations which I gave to the patient, the paper contains a number of conclusions drawn from the material, and I shall not at every point make a clear distinction between these two categories. A consistent demarcation of such a kind would involve a good deal of repetition and blur the main issues.

Early anxieties impeding Oedipus development

I take as my starting point the resumption of the analysis after a break of ten days. The analysis had by then lasted six weeks. During this break I was in London, and Richard went away on holiday. He had never been in an air-raid, and his fears of air-raids centred on London as the place most in danger. Hence to him my going to London meant going to destruction and death. This added to the anxiety which was stirred up in him by the interruption of the analysis.

On my return I found Richard very worried and depressed. During the whole first hour he hardly looked at me, and alternated between sitting rigidly on his chair without lifting his eyes and wandering out restlessly into the adjoining kitchen and into the garden. In spite of his marked resistance he did, however, put a few questions to me: Had I seen much of ‘battered’ London? Had there been an air-raid while I was there? Had there been a thunderstorm in London?

One of the first things he told me was that he hated returning to the town where the analysis took place, and called the town a ‘pig-sty’ and a ‘nightmare’. He soon went out into the garden, where he seemed more free to look around. He caught sight of some toadstools which he showed to me, shuddering and saying they were poisonous. Back in the room, he picked up a book from the shelf and particularly pointed out to me a picture of a little man fighting against an ‘awful monster’.

On the second day after my return Richard told me with great resistance about a conversation he had had with his mother while I was away. He had told his mother that he was very worried about his having babies later on and had asked her whether it would hurt very much. In reply she had, not for the first time, explained the part played by the man in reproduction, whereupon he had said he would not like to put his genital into somebody else’s genital: that would frighten him, and the whole thing was a great worry to him.

In my interpretation I linked this fear with the ‘pig-sty’ town; it stood in his mind for my ‘inside’ and his mother’s ‘inside’, which had turned bad because of thunderstorms and Hitler’s bombs. These represented his ‘bad’ father’s penis entering his mother’s body and turning it into an endangered and dangerous place. The ‘bad’ penis inside his mother was also symbolized by the poisonous toadstools which had grown in the garden in my absence, as well as by the monster against which the little man (representing himself) was fighting. The phantasy that his mother contained the destructive genital of his father accounted in part for his fears of sexual intercourse. This anxiety had been stirred up and intensified by my going to London. His own aggressive wishes relating to his parents’ sexual intercourse greatly added to his anxieties and feelings of guilt.

There was a close connection between Richard’s fear of his ‘bad’ father’s penis inside his mother and his phobia of children. Both these fears were closely bound up with the phantasies about his mother’s ‘inside’ as a place of danger. For he felt he had attacked and injured the imaginary babies inside his mother’s body and they had become his enemies. A good deal of this anxiety was transferred on to children in the external world.

The first thing Richard did with his fleet during these hours was to make a destroyer, which he named ‘Vampire’, bump into the battleship ‘Rodney’, which always represented his mother. Resistance set in at once and he quickly rearranged the fleet. However, he did reply—though reluctantly—when I asked him who the ‘Vampire’ stood for, and said it was himself. The sudden resistance, which had made him interrupt his play, threw some light on the repression of his genital desires towards his mother. The bumping of one ship against another had repeatedly in his analysis turned out to symbolize sexual intercourse. One of the main causes of the repression of his genital desires was his fear of the destructiveness of sexual intercourse because—as the name ‘Vampire’ suggests—he attributed to it an oral-sadistic character.

I shall now interpret Drawing I, which further illustrates Richard’s anxiety situations at this stage of the analysis. In the pattern drawings, as we already know, red always stood for Richard, black for his father, purple for his brother and light blue for his mother. While colouring the red sections Richard said: These are the Russians.’ Though the Russians had become our allies, he was very suspicious of them. Therefore, in referring to red (himself) as the suspect Russians, he was showing me that he was afraid of his own aggression. It was this fear which had made him stop the fleet game at the moment when he realized that he was being the ‘Vampire’ in his sexual approach to his mother.

Drawing I expressed his anxieties about his mother’s body, attacked by the bad Hitler-father (bombs, thunderstorms, poisonous toadstools). As we shall see when we discuss his associations to Drawing II, the whole empire represented his mother’s body and was pierced by his own ‘bad’ genital. In Drawing I, however, the piercing was done by three genitals, representing the three men in the family: father, brother and himself. We know that during this hour Richard had expressed his horror of sexual intercourse. To the phantasy of destruction threatening his mother from his ‘bad’ father was added the danger to her from Richard’s aggression, for he identified himself with his ‘bad’ father. His brother too appeared as an attacker. In this drawing his mother (light blue) cont...