![]()

1

Introduction to the Core Dilemma

If we are to transform our state of virtual equality, evident in pervasive discrimination, ambivalent public opinion, and the persistence of the closet, we must begin with ourselves—both individually and as a movement. Coming out is the one step each gay, lesbian, or bisexual person can take to shatter virtual equality and move closer to the genuine equality with heterosexuals that is our birthright as moral human beings. Our challenge as a movement requires an examination of the strategies that have brought us to this troubling juncture.

—Urvashi Vaid, Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay and Lesbian Liberation

Trying to find common ground for political mobilization among all these identities has become one of the most difficult tasks of what has come to be called the gay rights movement.

—Robert Bailey, Gay Politics, Urban Politics: Identity and Economics in the Urban Setting

URVASHI VAID’S AND ROBERT BAILEY’S OBSERVATIONS CAPTURE the challenges facing the contemporary lesbian and gay rights movements.1 Vaid and Bailey point to the reality that all social movements, including the lesbian and gay movements, must constantly examine their broader political, social, and cultural approaches to change. The goal is to assess the difficulties and possibilities that have faced the movements over time with an eye toward what might be done in the future to expand the traditional notions of democracy and citizenship.

This is a particularly auspicious time to engage in this kind of critical examination, given the increasing cultural visibility of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and those who are transgendered, reflected in an array of popular television shows, including Glee, Shameless, Mad Men, Downton Abbey, Modern Family, The L Word, Queer as Folk, Six Feet Under, Will and Grace, The Sopranos, Rescue Me, Nip/Tuck, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Oz, NYPD Blue, and The Shield, to name a few. And when a moving, mainstream Hollywood film, Brokeback Mountain, receives considerable critical praise from reviewers and enthusiastic attention by the moviegoing public, one recognizes the sea change that has taken place since even the mid-1990s. But what does this visibility really mean for people’s daily lives? In recent years we have seen increased public tolerance and support for people coming out of the closet. Indeed, Margaret Talbot has written in the New Yorker that “the more gay friends, family members, and co-workers straight people know they have, and the more gay celebrities they are aware of, the harder it is for society to deny rights on the basis of some specious presumption of otherness” (Talbot 2013, 21). The students I teach now are more likely to be supportive of their “out” peers than others were even ten years ago. And courses related to the lesbian and gay movements across academic disciplines are often among the most popular offerings on college campuses. This undoubtedly reflects the political organizing and education of earlier eras and the salience of these complicated and challenging issues to young people’s lives.

At the same time, the lesbian and gay movements have achieved tangible accomplishments establishing open communities of lesbians and gay men in urban areas throughout the United States. In addition, openly gay men and lesbians have been successful in the electoral arena, from city councils to state legislatures to the US Congress. Indeed, Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) is the first openly lesbian or gay member of the United States Senate, elected in 2012. Community organizations and businesses target the interests of the lesbian and gay movements. And some progress has been made through the legal system, most notably in the Supreme Court’s 2003 Lawrence v. Texas decision that ruled state sodomy laws unconstitutional. As the constitutional historian Michael Klarman has accurately pointed out, “fifty years ago, every state criminalized same-sex sodomy; today it is a constitutional right.” And Klarman correctly celebrates progress that the movements have made in fighting employment discrimination as well: “Thirty years ago, not a single state barred discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment or public accommodations; today more than twenty states have enacted such laws” (Klarman 2013, 218).

College and professional sports are beginning to mirror changes in society writ large. In 2013, Robbie Rogers, an outstanding professional soccer player, publicly identified himself as gay and, within several months, signed a professional contract with the LA Galaxy, as an out, proud gay man. Brittney Griner, a women’s college basketball star at Baylor University, came out of the closet to little fanfare and signed a professional contract to play with the Phoenix Mercury of the WNBA. Jason Collins, a journeyman center who had played for five NBA teams and was still an active player, came out on Sports Illustrated’s website on April 29, 2013, followed by a cover story in the May 6, 2013, issue of the magazine. Collins’s coming out story was greeted with considerable fanfare as he became the first male athlete from one of the four major professional sports (baseball, basketball, football, hockey) to do so. On Sunday, February 23, 2014, Collins became the first openly gay professional player, after signing a ten-day contract with the NBA’s New Jersey Nets earlier in the day. He debuted that evening when the Nets played the Lakers in Los Angeles. Neither the NFL, MLB, or NHL had ever had an openly gay athlete prior to Collins’s debut. Collins’s groundbreaking act and the New Jersey Nets’ willingness to afford Collins the opportunity, will undoubtedly inspire other professional athletes to come out while active participants in their respective sports.

Indeed, in February 2014, in an act of tremendous courage, University of Missouri defensive lineman and graduating senior, Michael Sam, announced that he is gay in interviews with ESPN and the New York Times. Sam had previously come out to his entire college football team in August 2013 and received tremendous support from his coaches and teammates. His announcement came roughly two months before the NFL draft and led to widespread speculation that it would continue to pave the way for other gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender athletes in professional sports.

But for all of the so-called progress, lesbians and gay men remain second-class citizens in vital ways. For example, though in May 2013 the Boy Scouts of America ended its long-term policy of preventing openly gay youths from participating in any of its organizational activities, this major policy change, effective in January 2014, was passed only after considerable acrimony and internal organizational debate. Although this development was viewed as evidence of progress by some in the lesbian and gay movements, the policy was undercut by the inability of the organization to address “the even more divisive question of whether to allow openly gay adults and leaders” (Eckholm 2013, A1). In doing so, the Boy Scouts of America reinforced the worst assumptions of out adults who are in organizational leadership positions.

In addition, there is considerable societal disagreement over an array of interrelated issues, including same-sex marriage, adoption of children by same-sex couples, and ordination of lesbian and gay people into the clergy (Olson, Djupe, and Cadge, 2011, 189). Out lesbians, gays, and bisexuals occupy less than one-tenth of 1 percent of all elected offices in this country (Sherrill 1996, 469); very few transgendered people have been elected to public office. In most states, lesbians and gay men are forbidden to marry, to teach in many public schools, to adopt children, and to provide foster care. If evicted from their homes, expelled from their schools, fired from their jobs, or refused public lodging, they usually are not able to seek legal redress. The topic of homosexuality is often deemed inappropriate for discussion in public schools, including in sex education courses. Many public school libraries refuse to carry some of the many books that address the issue in important ways. Lesbians and gays are often reviled by the church and barred from membership in the clergy. They are the victims of hate crimes and targets of verbal abuse, and the possibility still exists that they will be beaten, threatened, attacked, or killed for simply loving another human being. Their parents reject them, and many gay youth have either attempted or contemplated suicide. Indeed, political scientist Mark Hertzog concludes that “no other group of persons in American society today, having been convicted of no crime, is subject to the number and severity of legally imposed disabilities as are persons of same-sex orientation” (1996, 6).

What does all of this mean for how the contemporary lesbian and gay movements conceive of their political organizing strategies, especially given the determination by the Christian Right to use lesbian and gay issues, such as same-sex marriage, as wedge issues in elections at all levels of government? Should policy and cultural change reflect a top-down model, or should it be inspired by grassroots organizing in local communities throughout the United States? And should the goal be a more assimilationist, rights-based approach to political and social change, or should movement activists embrace a more liberationist, revolutionary model, one that might embrace a full range of progressive causes? This last question is the central dilemma of this book, given how the assimilationist and liberationist approaches have been integral to the lesbian and gay movements’ organizing over the past sixty years.

Throughout their relatively short history, the lesbian and gay movements in the United States have endured searing conflicts over which strategy to embrace. This book explores this dilemma in both contemporary and historical contexts within a broader social-movement theoretical setting. The assimilationist approach typically embraces a rights-based perspective, works within the broader framework of pluralist democracy—one situated within classical liberalism—and fights for a seat at the table. In doing so, the assimilationists celebrate the “work within the system,” or “let us in,” insider approach to political activism, rather than the “let us show you a new way of conceiving the world” strategy associated with lesbian and gay liberation. Assimilationists are more likely to accept that change will have to be incremental and to understand that slow, gradual progress is built into the very structure of the US framework of government.

A second approach, the liberationist perspective, favors more radical cultural change, change that is transformational in nature and often arises outside the formal structures of the US political system. Liberationists argue that there is a considerable gap between access and power and that it is not enough to simply have a seat at the table. For many liberationists, what is required is a shift in emphasis from a purely political strategy to one that embraces both structural political and cultural change, often through “outsider” political strategies. The notion of sexual citizenship embraced by liberationist activists and theorists is much more broadly conceived, as sociologist Steven Seidman describes: “buoyed by their gains, and pressured by liberationists, the gay movement is slowly, if unevenly, expanding its political scope to fighting for full social equality—in the state, in schools, health-care systems, businesses, churches, and families” (2002, 24). Political theorist Shane Phelan claims that liberationists often “attempt to subvert the hierarchies of the hegemonic order, pointing out the gaps and contradictions in that order, thus removing the privilege of innocence from the dominant group” (2001, 32). As I will demonstrate, the assimilationist and liberationist strategies are not mutually exclusive.

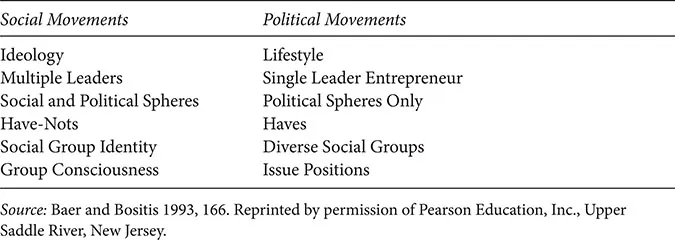

FIGURE 1.1 Social and Political Movements Compared

To better explicate the book’s central dilemma, I will couch my analysis within the broader context of social-movement theory. First, it is necessary to understand how social movements differ from political parties, interest groups, and protests. They have three distinguishing features: they grow out of “a mass base of individuals, groups, and organizations, linked by social interaction,” they “organize around a mix of political and cultural goals,” and they “rely on a shared collective identity that is the basis of mobilization and participation” (Wald 2000, 5). Political scientist Sidney Tarrow extends this definition, stating that social movements involve “mounting collective challenges, drawing on common purposes, building solidarity and sustaining collective action” (1994, 3). They are also decentralized and comprise an array of organizations. They are often confused with political movements, but there are key differences between them, as Figure 1.1 demonstrates.

Unlike political movements, which tend to represent middle-class interests, social movements tend to represent those at the margins of American society, as defined by class, race, gender, or sexual orientation. Political movements are often defined through a single leader and her or his organization, whereas social movements are generally much more decentralized and sometimes have no real leader per se. Finally, social movements develop a comprehensive ideology, whereas political movements most often focus on narrow objectives such as handgun control or the nuclear freeze. Often, social movements push for political change at the same time they seek structural change in the social, cultural, economic, and private spheres (Baer and Bositis 1993). At their core, social movements inspire participatory democracy.

[Social movements] raise expectations that people can and should be involved in the decision-making process in all aspects of public life. They convert festering social problems into social issues and put them on the political agenda. They provide a role for everyone who wants to participate in the public process of addressing critical social problems and engaging official power holders in a response to grassroots citizen demands for change. In addition, by encouraging widespread participation in the social change process, over time social movements tend to develop more creative, democratic, and appropriate solutions. (Moyer et al. 2001, 10)

The lesbian and gay movements certainly meet the criteria for an existing social movement. Lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgendered people have persistently occupied a place at the margins of society.

The vulnerability of groups at the margins of US society permits elites to create serious obstacles to political participation and control of the political agenda (Scott 1990, 72). In response to their structural and cultural marginalization, groups outside the mainstream identify strategies that they perceive will meet their needs while challenging structures that constrain their life choices. These strategies commonly include developing alternative resources, constructing different ideological frameworks, and creating oppositional organizations and institutions. Such structures are most often “grounded in the indigenous or communal relationships of marginal groups” (C. Cohen 1999, 48). This is especially true for the lesbian and gay movements.

From the vantage point of marginalized groups, then, social movements are vehicles for organization, education, and resistance. They are often galvanized when they perceive “changes in political opportunities that give rise to new waves of movements and shape their unfolding.” Successful social movements build on political opportunities by seizing and expanding them, thus turning them into collective action (Tarrow 1994, 7). I will examine how well the lesbian and gay movements have done so by studying the intersection between the assimilationist and liberationist strategies over time. We will see that social-movement politics are conflictual, messy, and complicated; they defy easy generalizations and their behavior often eludes simple explanations.

Chapter 2 places the development of the lesbian and gay movements within their proper historical context. Particular attention is devoted to the development of the assimilationist and liberationist approaches over the past sixty years by examining the creation and goals of the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis in the 1950s, the rise of the homophile movement in the 1950s and 1960s, and the connections between that movement and the movements growing out of the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969.

The assimilationist-accommodationist strategy prevailed within the broader movements until Stonewall. Despite their accomplishments, Stonewall threw mainstream homophile organizations on the defensive, as newly energized lesbian and gay activists, many of them veterans of the various movements of the 1960s, demanded a new style of political organizing and leadership. This more confrontational liberationist approach embraced militancy and the unconventional politics associated with the antiwar, women’s liberation, and civil rights movements. The modern gay liberation movement was soon born, built on some of the same ideas that undergirded the original Mattachine Society envisioned by Harry Hay and his cofounders almost twenty years earlier. For those who embraced gay liberation, a rights-based strategy was far too limited. The goal should be to remake, not merely reform, society. Chapter 2 explores these conflicts within the broader movements throughout the 1970s and 1980s, which were dominated by the rise of a conservative insurgency in society at large. The response of the Christian Right to the movements’ gains in the 1970s and early 1980s is also examined in considerable detail.

Chapter 3 explores the tensions between those activists who embraced an insider assimilationist strategy and those who demanded an outsider liberationist stra...