With the emergence, during World War II, of Abstract Expressionist painting (also known as Action Painting and the New York School), the United States began to play a major role in world art. The presence of several important European artists, especially Mondrian and the Surrealists—actually living right there, in the same place, during those years—was a profoundly liberating force to our artists, as Pollock acknowledges.

Jackson Pollock (1912-1956)

Jackson Pollock, Response to questionnaire, Arts and Architecture (February 1944)

This early statement by the artist who is universally identified with the American breakthrough in the 1940s was effectively titled simply by Pollock’s signature, with no interviewer named. Francis O’Connor ascertained from the artist’s widow, Lee Krasner, that the questionnaire was “formulated by Pollock with the assistance of Howard Putzel.”* Putzel was associated with the Art of This Century Gallery, where, during the war years, the expatriate Peggy Guggenheim showed the work of the European Surrealists whom she had brought here, as well as that of several of the Americans who later became known as Abstract Expressionists.

* * *

Where were you born?

J.P.: Cody, Wyoming, in January, 1912. My ancestors were Scotch and Irish.

Have you traveled any?

J.P.: I’ve knocked around some in California, some in Arizona. Never been to Europe.

Would you like to go abroad?

J.P.: No. I don’t see why the problems of modern painting can’t be solved as well here as elsewhere.

Where did you study?

J.P.: At the Art Student’s League, here in New York. I began when I was seventeen. Studied with Benton, at the League, for two years.

How did your study with Thomas Benton affect your work, which differs so radically from his?

J.P.: My work with Benton was important as something against which to react very strongly, later on; in this, it was better to have worked with him than with a less resistant personality who would have provided a much less strong opposition. At the same time, Benton introduced me to Renaissance art.

Why do you prefer living here in New York to your native West?

J.P.: Living is keener, more demanding, more intense and expansive in New York than in the West; the stimulating influences are more numerous and rewarding. At the same time, I have a definite feeling for the West: the vast horizontality of the land, for instance; here only the Atlantic Ocean gives you that.

Has being a Westerner affected your work?

J.P.: I have always been very impressed with the plastic qualities of American Indian art. The Indians have the true painter’s approach in their capacity to get hold of appropriate images, and in their understanding of what constitutes painterly subject matter. Their color is essentially Western, their vision has the basic universality of all real art. Some people find references to American Indian art and calligraphy in parts of my pictures. That wasn’t intentional; probably was the result of early memories and enthusiasms.

Do you consider technique to be important in art?

J.P.: Yes and no. Craftsmanship is essential to the artist. He needs it just as he needs brushes, pigments, and a surface to paint on.

Do you find it important that many famous modern European artists are living in this country?

J.P.: Yes. I accept the fact that the important painting of the last hundred years was done in France. American painters have generally missed the point of modern painting from beginning to end. (The only American master who interests me is Ryder.) Thus the fact that good European moderns are now here is very important, for they bring with them an understanding of the problems of modern painting. I am particularly impressed with their concept of the source of art being the unconscious. This idea interests me more than these specific painters do, for the two artists I admire most, Picasso and Miró, are still abroad.

1. Jackson Pollock, Guardians of the Secret, 1943. Oil on canvas, 48¾ × 75 in. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Bequest Fund Purchase.

Do you think there can be a purely American art?

J.P.: The idea of an isolated American painting, so popular in this country during the thirties, seems absurd to me, just as the idea of creating a purely American mathematics or physics would seem absurd…. And in another sense, the problem doesn’t exist at all; or, if it did, would solve itself: An American is an American and his painting would naturally be qualified by that fact, whether he wills it or not. But the basic problems of contemporary painting are independent of any one country.

Jackson Pollock, “My Painting,” Possibilities I (Winter 1947-48)

This brief document, which included six illustrations of Pollock’s paintings, appeared in the first and only issue of Possibilities, published by Wittenborn, Schultz, Inc., and edited by Robert Motherwell, art; Harold Rosenberg, writing; Pierre Chareau, architecture; and John Cage, music. Pollock’s recorded statements are even more scant than Picasso’s—and nearly as influential. ‘On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I can walk around, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting” is as familiar to the student of contemporary art now as Picasso’s “When a form is realized it is there to live its own life” was thirty or forty years ago.

* * *

My painting does not come from the easel. I hardly ever stretch my canvas before painting. I prefer to tack the unstretched canvas to the hard wall or the floor. I need the resistance of a hard surface. On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting. This is akin to the method of the Indian sand painters of the West.

I continue to get further away from the usual painter’s tools such as easel, palette, brushes, etc. I prefer sticks, trowels, knives and dripping fluid paint or a heavy impasto with sand, broken glass and other foreign matter added.

When I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It is only after a sort of “get acquainted” period that I see what I have been about. I have no fears about making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through. It is only when I lose contact with the painting that the result is a mess. Otherwise there is pure harmony, an easy give and take, and the painting comes out well.

Excerpted from William Wright, “An Interview with Jackson Pollock,” 1950, quoted in Francis V. O’Connor, Jackson Pollock, New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1967.

Taped for the Sag Harbor radio station but not broadcast, this interview dates from the same year as Hans Namuth’s extraordinarily illuminating film of Pollock at work, in which the artist voices some of the ideas expressed in these three documents.

* * *

W.W.: Mr. Pollock, in your opinion, what is the meaning of modern art?

J.P.: Modern art to me is nothing more than the expression of contemporary aims of the age that we’re living in.

W.W.: Did the classical artists have any means of expressing their age?

J.P.: Yes, they did it very well. All cultures have had means and techniques of expressing their immediate aims—the Chinese, the Renaissance, all cultures. The thing that interests me is that today painters do not have to go to a subject matter outside of themselves. Most modern painters work from a different source. They work from within.

W.W.: Would you say that the modern artist has more or less isolated the quality which made the classical works of art valuable, that he’s isolated it and uses it in a purer form?

J.P.: Ah—the good ones have, yes.

W.W.: Mr. Pollock, there’s been a good deal of controversy and a great many comments have been made regarding your method of painting. Is there something you’d like to tell us about that?

J.P.: My opinion is that new needs need new techniques. And the modern artists have found new ways and new means of making their statements. It seems to me that the modern painter cannot express this age, the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio, in the old forms of the Renaissance or of any other past culture. Each age finds its own technique.

W.W.: Which would also mean that the layman and the critic would have to develop their ability to interpret the new techniques.

J.P.: Yes—that always somehow follows. I mean, the strangeness will wear off and I think we will discover the deeper meanings in modern art.

W.W.: I suppose every time you are approached by a layman they ask you how they should look at a Pollock painting, or any other modern painting—what they look for—how do they learn to appreciate modern art?

J.P.: I think they should not look for, but look passively—and try to receive what the painting has to offer and not bring a subject matter or preconceived idea of what they are to be looking for.

W.W.: Would it be true to say that the artist is painting from the unconscious, and the—canvas must act as the unconscious of the person who views it?

J.P.: The unconscious is a very important side of modern art and I think the unconscious drives do mean a lot in looking at paintings.

W.W.: Then deliberately looking for any known meaning or object in an abstract painting would distract you immediately from ever appreciating it as you should?

J.P.: I think it should be enjoyed just as music is enjoyed—after a while you may like it or you may not. But—it doesn’t seem to be too serious. I like some flowers and other flowers I don’t like. I think at least … give it a chance.

W.W.: ... A person would have to subject himself to it [modern painting] over a period of time in order to be able to appreciate it.

J.P.: I think that might help, certainly.

W.W.: Mr. Pollock, the classical artists had a world to express and they did so by representing the objects in that world. Why doesn’t the modern artist do the same thing?

J.P.: H’m—the modern artist is living in a mechanical age and we have a mechanical means of representing objects in nature such as the camera and photograph. The modern artist, it seems to me, is working and expressing an inner world—in other words—expressing the energy, the motion, and other inner forces.

W.W.: Would it be possible to say that the classical artist expressed his world by representing the objects, whereas the modern artist expresses his world by representing the effects the objects have upon him?

J.P.: Yes, the modern artist is working with space and time, and expressing his feelings rather than illustrating.

W.W.: … Can you tell us how modern art came into being?

J.P.: It didn’t drop out of the blue; it’s a part of a long tradition dating back with Cézanne, up through the Cubists, the Post-Cubists, to the painting being done today.

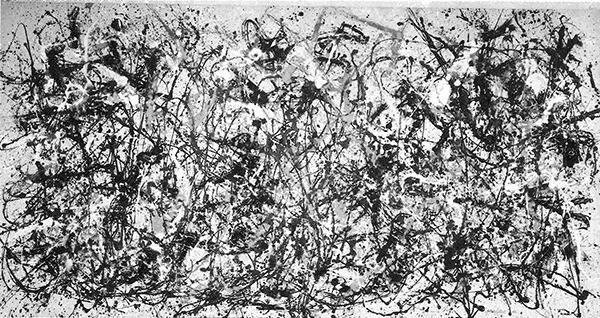

2. Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm, 1950. Oil on canvas, 105 × 207 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, George A. Hearn Fund, 1957.

W.W.: Then, it’s definitely a product of evolution?

J.P.: Yes.

W.W.: … Can you tell us how you developed your method of painting, and why you paint as you do?

J.P.: Well, method is, it seems to me, a natural growth out of a need, and from a need the modern artist has found new ways of expressing the world about him. I happen to find ways that are different from the usual techniques of painting, which seems a little strange at the moment, but I don’t think there’s anything very different about it. I paint on the floor and this isn’t unusual—the Orientals did that.

W.W.: How do you go about getting the paint on the canvas? …

J.P.: Most of the paint I use is a liquid, flowing kind of paint. The brushes I use are used more as sticks rather than brushes—the brush doesn’t touch the surface of the canvas, it’s just above.

W.W.: Would it be possible for you to explain the advantage of using a stick with liquid paint rather than a brush on canvas?

J.P.: Well, I’m able to be more free and to have a greater freedom and move about the canvas, with greater ease.

W.W.: … Isn’t it more difficult to control than a brush? …

J.P.: No, I don’t think so … with experience—it seems to be possible to control the flow of the paint, to a great extent, and... I don’t use the accident—’cause I deny the accident.

W.W.: I believe it was Freud who said there’s no such thing as an accident. Is that what you mean?

J.P.: I suppose that’s generally what I mean.

W.W.: Then, you don’t actually have a preconceived image of a canvas in your mind?

J.P.: Well, not exactly—no—because it hasn’t be...