This is a test

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This clear, thorough, and reliable survey of American painting and sculpture from colonial times to the present day covers all the major artists and their works, outlines the social and cultural backgrounds of each period, and includes 409 illustrations integrated with the text. Although some determining factors in American art are considered, Matthew Baigell views the rich and diverse achievements of American art as the result of the efforts and talents of a pluralistic society rather than as fitting into a particular mold.This edition includes corrections and revisions to the text, an updated bibliography, and 13 new illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Concise History Of American Painting And Sculpture by Matthew Baigell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art général. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Colonial Art

NORTHWESTERN EUROPEANS established permanent colonies on the eastern shores of what is now the United States throughout the seventeenth century. English groups settled in tidewater Virginia at Jamestown in 1607; along the New England coast on Cape Cod in 1620 (the Pilgrims); at Salem, Massachusetts, in 1628 (the Puritans); and in the Chesapeake Bay area in 1634. Beginning in 1624, the Dutch began to colonize the Hudson River area, but succumbed to English rule in 1664. In the 1660s, the first settlements were started in the Carolinas and, by 1680, in the Delaware Bay region. At the end of the century, the English controlled the entire seaboard from Portland, Maine, to Port Royal, below Charleston, in South Carolina. In the 1640s, about 50,000 Europeans and Africans lived in the colonies; by 1700, the number had jumped to about 200,000; and, in 1720, to almost half a million.

Because of the patterns of settlement—dispersed plantations in the South and populated towns in the North—the most noteworthy and extensive groups of paintings surviving the first century of immigration come from the areas around Boston and New York City. At least one painter, Augustine Clemens (c. 1600–74), arrived in Massachusetts as early as 1635, but the earliest surviving works date only from 1664. By that time, the rigors of pioneer life and, more important, the rigors of Puritan faith had begun to wane. The Sumptuary Law of 1651, passed by the Massachusetts General Court, ruled against people of “mean condition” dressing above their station, as ladies and gentlemen, thus acknowledging that many people no longer showed their inner sanctity by their outer appearance or honored the class-leveling implications of Puritan religious fellowship. Although conservative elders continued to thunder against the growing interest in worldly goods and pleasures, the rising merchant class and the burgeoning transient population, especially in larger towns, could no longer be controlled. The earlier ideal of self-control and proper religious behavior had so deteriorated by 1675 that the General Court, realizing that many heads of families no longer performed their duties properly, appointed tithing men to see that the Sabbath was observed and that drinking was controlled. (Boston had at least fourteen inns or taverns by 1662.) In addition, the very success of the colonies altered the once central role of ministers, who had earlier participated in and guided the practical affairs of their communities, but whose place was increasingly narrowed to that of professionals catering only to the spiritual needs of their congregations.

Quite possibly, a painting such as Mrs. Freake and Baby Mary, 1674 [1], could not have been painted a generation earlier—and not only because Mrs. Freake allowed the artist to dwell so carefully on her fine clothing, of which she must have been very proud. The Puritans often gave their children to other families to be raised because they feared spoiling their youngsters with too much affection. Parental indulgence might, the Puritans thought, prevent a child from learning to control his or her feelings. Although Mrs. Freake does not show great warmth toward her daughter—the exploration of human emotions was not important in Puritan culture—she displays an obvious pleasure that probably would have caused the earliest settlers to wonder about the future of their Bible commonwealth.

1. Anonymous, Mrs. Elizabeth Freake and Baby Mary, c. 1674. Worcester Art Museum.

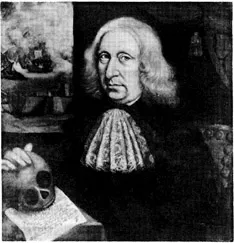

2. John Foster (?), Reverend John Davenport, late seventeenth century. Yale University Art Gallery.

Mrs. Freake and Baby Mary is one of several paintings similar in style. These are characterized by minimal modeling of the face and arms, emphasized linear contours, clearly depicted patterns, and bright colors that hide body volumes. The figures are usually in a frontal position, and, with background elements barely indicated, depth is severely limited. Although it has been suggested that Samuel Clemens (d. 1768), Augustine’s son, painted Mrs. Freake and her daughter, the work was probably done by a more recent arrival from England. Compared to similarly styled works, this one, unless significantly altered by cleanings and repaintings, is the most thorough, complete, and consistent in all its parts and details, indicating that its author had received more than rudimentary training and had, at least in his mind’s eye, excellent models on which to base his painting. If the artist was a Puritan, his presence at this time in New England might be explained by the brutal repression of Puritans after Charles II’s accession to the throne in 1660. In any event, sources for the artist’s work and style lie in provincial English paintings of a generation or two earlier from East Anglia, the area northeast of London from which many settlers emigrated.

3. Thomas Smith, Self-Portrait, late seventeenth century. Worcester Art Museum.

In addition to the linear style, which developed from old English modes, East Anglian artists were also influenced by realistic Dutch works because of commercial trade between the two areas. Versions of this style also appeared in New England by 1670, and at least one figure, John Foster (1648–81), can even be identified with it. His woodcut of John Mather, c. 1670, probably the first print made in the English colonies, resembles several portraits of New England ministers. Perhaps it was Foster who painted the portrait of the Reverend John Davenport [2], one of the most conservative of the old-fashioned ministers, shortly before Davenport’s death in 1670. (Davenport, a founder of New Haven and a minister there, took over the pulpit of Boston’s First Church in 1668.)

In contrast to the linear-styled works, the realistic style is characterized by a greater degree of modeling and psychological insight, despite the stereotyped poses. Like the painter of Mrs. Freake, the artist or artists of the more realistic style could not create atmospheric envelopes around their figures. The accented faces and hands, therefore, do not assume a vibrancy and living presence typical of European works, but have a stiffness of form in which parts of bodies seem frozen, anchored in a sea of darker colors. On the other hand, loss of depth denies these figures a physical and sensuous palpability, a quality the conservative Puritans would have abhorred anyway. Here, religious belief and lack of training seem to coincide.

A third group of colonial works, associated mainly with a mariner, Captain Thomas Smith, reflect contemporary English courtly styles [3]. In these works, Dutch realism is modified by familiarity with the pomp, splendor, and grace of Flemish baroque art, introduced into England by Sir Anthony Van Dyck in 1620. Van Dyck visited England that year, and he lived there from 1632 to 1641, setting the course of aristocratic portraiture for the next two hundred years. His successors—who were important because their paintings, copied in mezzotints, served as models for American painters throughout the colonial period—were Sir Peter Lely (1618–80), who settled in England in 1641, and Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723), who arrived there in 1674. Both were trained in Holland.

Captain Smith, obviously familiar with London fashions, visited the colonies as early as 1650. Able to model features convincingly, Smith also included distant vistas in his work, a characteristic device of the Van Dyck school. But one may argue that, even though this group of colonial paintings was the most stylistically advanced, it tells us the least about Puritan culture. Rather, it describes the aspirations that ultimately dominated New England culture; the descendants of those who wanted to purify the Church of England turned themselves into provincial imitators of their cosmopolitan English cousins.

The emphasis on portraits throughout the colonial period reflects English taste and religious practice, which proscribed religious scenes. But the first settlers did not consider a face painter more valuable than any other craftsperson. The tradition of the great artist, imported from the Continent, had not yet reached England and, besides, Puritans judged a person by signs of inner grace, of the presence of the living God in one’s soul, rather than by a facility with a paintbrush—thus, the anonymity of most portrait painters.

Religious imagery was especially disliked by the Puritans, whose chief mode of communication was verbal rather than visual, and who preferred the sermon to the sensuous effects of an elaborate worship service and elevated the pulpit above the altar. Yet, they developed a mortuary art in the seventeenth century that lasted in rural areas until the nineteenth. The dead, evidently, could not easily be buried without a commemorative gravestone. Students of the period have not yet explained the popularity of gravestones in a religious culture that preferred discourse and rational explanation to imagery and emotion. Probably the fact of death itself was too monstrous to face without symbolically sending off the recently deceased to the other side. Images carved on tombstones might well have had the salutary effect of providing a more direct, personal access to the mysterious workings of the Deity than what was heard in dry, emotionless sermons. The desire and need for a more immediate rapport with God lay just beneath the surface of Puritan thought. This is reflected in Anne Hutchinson’s trial and banishment in 1637 for believing that God had revealed Himself directly to her and by the Great Awakening of the 1740s, in which people felt the divine infusion of grace without necessarily having to prepare for it or having to act responsibly because of it. (Nineteenth-century Transcendentalism might be considered a later version of the same longing for direct communion with the godhead.)

For the Puritans, death was viewed as a lesson for the living. That is, people were taught to trust in God and to contain their emotions in the face of death. Accordingly, the carvings on the tombstones showed a variety of images that confronted the viewer both with the stern reality of death and with the hoped-for afterlife. In place of the narrative imagery common to Catholic art, there were symbols of death and rebirth, including death’s heads and glorified souls, as well as skeletons and living vines. Styles ranged from shallow-planed rural reliefs to deeply cut carvings in urban cemeteries. As in contemporary paintings, European influences appeared to a greater or lesser degree, intermingled with forms apparently of local invention.

4. Anonymous, Joseph Tapping Stone, 1678.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, several schools and individual carvers had become well known. The Joseph Tapping Stone, 1678 [4], roughly contemporary with the earliest surviving Puritan paintings, is among the more elaborate of its time. Done in the workshop of an artisan now known as the Charlestown Carver, it has architectural motifs of gothic arches and columns, suggesting the journey to Heaven through these portals. The centrally placed death’s head commonly appeared on Boston gravestones of the period. The allegory of time and death, based on sources in English emblem books, was perhaps the first such image to appear in New England.

Painting in the New York City area is much less problematic in respect to content than in New England, but infinitely more complicated in regard to chronology and identification of artists. Manhattan Island, first settled in 1624, primarily as a trading center, had only 1500 people when the British captured it in 1664. It had a rowdy town, open to virtually all religions and nationalities, but it could boast of several artists, including the Frenchman Henri Couturier, who worked there through the 1660s and in the early 1670s. Couturier, or another...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Colonial Art

- 2 The New Nation

- 3 Self-Discovery

- 4 At Home and Abroad

- 5 Early Modernism

- 6 Between the World Wars

- 7 International Presence

- 8 Contemporary Diversity

- Selected Bibliography

- Index