This is a test

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sports Architecture

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book offers a rare chance to understand how sport and architecture come together to create an outstanding building type - a symbol of our times. Rod Sheard shares the experience and expertise of HOK LOBB in this beautifully illustrated book, offering practical advice and guidance on commissioning, designing and managing sports venues around the world. The award-winning work of this firm includes the Millennium Stadium, Cardiff, the Wembley National Stadium, London and the Stadium Australia in Sydney, commissioned for the Olympic Games 2000.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Sports Architecture by Rod Sheard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Designing for Success | Part I |

Chapter 1

Sports architecture

‘We were there!’

Stadia are special buildings. They are the only structures designed to bring whole communities together so that they can interact with each other and as one with the event. We gather inside them to celebrate a unique experience. Yet so often the buildings themselves are dull and uninteresting. Sometimes they lack even the most basic of amenities and can be so bleak and unfriendly as to be almost frightening. The good news however, is that these outdated, inhospitable concrete bowls of the twentieth century are gradually disappearing.

A new generation of stadia is in the making. Mediocrity in design, management, catering, safety or comfort has no place in the new sporting cathedrals. Designers and clients are, at long last, waking up to the fact that the long-term health of any venue is directly dependent on two factors, the quality of the event and the quality of the spectator experience.

No one, surely, would doubt that the average living room provides a higher level of comfort and amenity than most stadia, or that televised coverage of a sporting event generally provides a better view of the action, with its close-ups, replays, commentary and interviews. But the critical ingredient which sets the live experience apart from its televised replica is the sense of ‘community’ a stadium creates, that gathering of people, focused, as one, upon a single transient show of human endeavour. This physical and emotional experience is the ‘product’ a stadium sells, a product quite unique in modern life. There is simply no other opportunity to be part of the crowd, to yell and jump and wave our arms at the same time as thousands of other people. The Mexican wave, the national songs or the club chants we perform with so many thousands of other strangers provide us with a deep, bonding reassurance that we are not alone, that we are part of a whole, part of something great. In going to the stadium rather than staying in our living rooms we can say, ‘We were there!’ (fig. 1.1)

From sports grounds to sports stadia

The sports stadium as we now know it today largely evolved in Britain’s industrialised cities during the nineteenth century. A number of factors created the need. The codification of a number of sports, particularly association football and rugby, had imposed a much-needed uniformity which allowed rival teams to compete in fair contests, bound by agreed rules and easily understood by those watching from the sidelines. Meanwhile, the development of the steam railway network enabled both teams and their followers to travel the country in pursuit of new challenges.

Inevitably, as the public demand increased for more meaningful, competitive games, the sporting authorities established regular league and cup competitions, which in turn increased the team’s need for higher quality players. Such players had to be paid, and so it was that sports grounds were enclosed so that money could be collected at a ‘gate’.

1.1 The opening of Stadium Australia, Sydney, was an opportunity to use the main truss as a base for a spectacular fireworks display (photography courtesy of the National Rugby League)

Whilst these early structures started as minimal wood, brick and steel compositions they were often elegant and articulate. But with the increasing use of concrete by the mid-twentieth century, the majority evolved into a forbidding building type, and a less useful one too. In their early days, many stadia were designed for field sports, athletics and sometimes even cycling. Eventually, however, the tracks were removed and the stadia became single-purpose facilities, serving a single-purpose crowd for a limited number of events each year. The rest of the time they lay unused, without function or patrons. Beyond a few hours’ sporting use every few weeks they were, in effect, dead buildings.

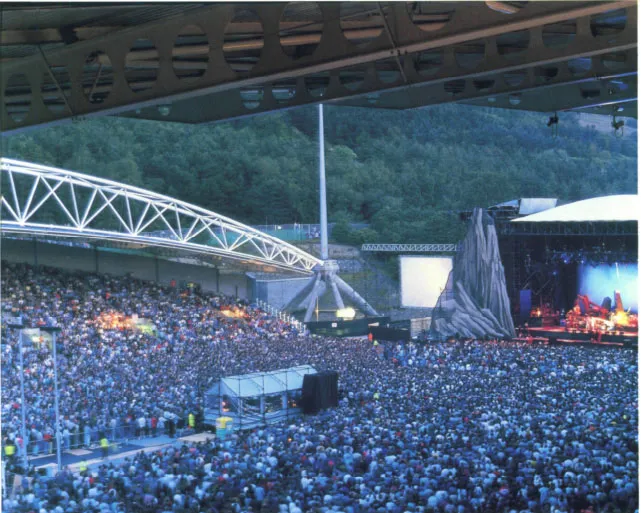

1.2 The Alfred McAlpine Stadium, Huddersfield, hosts the Eagles concert out of the football and rugby season

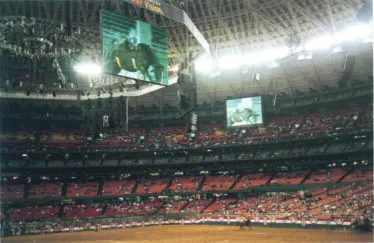

1.3 The Houston Astrodome, one of the first multi-purpose stadia, in use as a rodeo venue

1.4 Spectators arriving at Stadium Australia, Sydney with a sense of expectation (photography courtesy of the Olympic Coordination Authority (Bob Peters))

That hardly mattered as long as mass spectator sport remained one of the few forms of entertainment available. But in 1937 technology struck the sporting world for the first time when the BBC experimented with the live television broadcast of a football match from Arsenal Football Club (which happened to be near to the studios and transmitter at Alexandra Palace, in north London). It took a few years for the effects of broadcast sport to be felt, but by the late 1950s, television had penetrated so many homes that leisure patterns would never be the same again.

Faced with extra competition from television and the many other leisure pursuits that arose to satisfy the appetite of an increasingly affluent customer base, stadia were forced to adapt in order to survive. This change began in the USA during the 1960s with such pioneering venues as the Houston Astrodome, in 1965, one of the first sophisticated, multi-purpose and multi-user facilities which sought to attract a range of spectators beyond the hard core of sports fanatics who would attend events whatever the conditions. (Fig. 1.2, 1.3)

The contemporary stadium

To succeed in the latter half of the twentieth century a stadium must appeal to and be accepted by many different interest groups, not only the customers, participants, officials and event holders, but such diverse groups as local residents, local authorities, business sponsors, advertisers, concessionaires and media companies. All of these groups have needs. All can play a role. But it is important not to forget the three primary interest groups whose requirements are paramount. These are the spectators, the owner/operators and the participants, or the SOP, as they have come to be known.

– The spectators expect an enjoyable, safe day out in a stimulating environment. They are the primary group, without whose support the entire enterprise will fail

– The owner/operators expect to make a return on their investment. They will do this by attracting spectators to the venue in sufficient numbers and by managing them in a safe, efficient and organised manner. If they cannot manage the facility in such a way as to make it pay, either by operating income alone or by operating income + subsidy, the venue will close

– Without participants there are no events. Participants expect a good and safe standard of playing or performance conditions, ideally with large audiences and, in certain circumstances, good television and media coverage

These are the bare bones of a complex subject. As outlined more fully in Chapters 5–7, it is only by designing for each of these groups – by thinking through logically what each requires from the facility – that we have a chance of achieving a higher standard of design. For now, however, let us look more closely at our three primary interest groups.

The spectator

A happy spectator is one who looks forward to a special treat and whose expectations are not disappointed on the day. Spectators should be able to reach the stadium without undue difficulty; experience an agreeable sense of anticipation as they make their way to their seats through efficient entrances, safe ramps or stairways and pleasant concourses. When they have arrived they should be able to sit in comfort and safety with a clear view of the game. They should be fully informed and entertained during quiet moments by means of information displays, action playbacks and other devices that are better than what they would have seen on television at home. (Fig. 1.4)

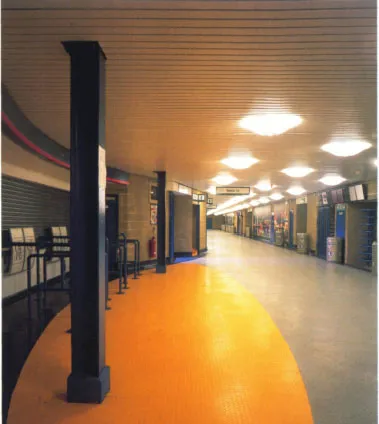

1.5 Concourses at Stadium Australia, Sydney

After the game spectators should not feel obliged to rush to the exit in order to avoid the crowds. They might, for example, prefer to linger in cafes, stay on at the stadium for a meal, or perhaps go shopping or spend time with their families in the stadium museum, games arcade or cinema. If they have come a long way or wish to stay in the area they might even like to spend a night in the stadium hotel, perhaps in a bedroom whose window overlooks the pitch (a room which, earlier in the day, might have been used by other spectators as a private viewing box). (Fig. 1.5, 1.6)

Successful stadia design requires that this entire sequence of experiences be clearly imagined by the client and his design team. The vision must be firmly cemented in their minds if it is to become a reality. Yet few clients have the knowledge or insight to conjure up this vision alone, which is where an experienced design team such as ours comes into play. Getting it right requires a sound knowledge of the motivations and desires of spectators, not as a monolithic mass but as a diverse collection of different kinds of people. Some may be sports enthusiasts for whom physical closeness to the game, to the players and to their fellow supporters is probably more important than comfort. At the other extreme, some may attend the games primarily for social reasons, or to entertain business associates. To them the game itself is less important than the overall experience of being pampered in an ambience of excitement, comfort and perhaps even exclusivity (in other words, making the occasion more ‘special’ than merely dining out at a restaurant). Between these two extremes are various intermediate types of spectator; for example, fans who take a real interest in sport but only attend stadia if they can take their families without feeling threatened by boisterous crowds or by the stadium environment itself.

1.6 Brightly coloured concourses at Chelsea Football Club

The owner/operator

Until recently the owner or operator’s prime source of revenue was ticket receipts or income collected at the gate, hence the importance of what has been crudely described as ‘bums on seats’. (There is an old story concerning a London gentleman who arrived at a Yorkshire cricket ground early and so placed a newspaper on his preferred seat while he went to enjoy some pre-match victuals. On his return he found a local man sitting on his newspaper. When he complained, the man replied somewhat equivocally, ‘It’s bums what reserve seats round here.’)

Although ticket revenue remains important, evidence from stadia around the world shows that it is gradually decreasing as a percentage of the owner/operator’s total income. Rather, it forms a base for other types of revenue generation. Such ‘non-gate income’ tends to fall into one of two categories: that derived from the event itself (for example, game sponsorship, ad...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword by Simon Inglis

- Introduction

- Part I Designing for Success

- Part II Case Studies

- Part III The Future