![]()

Meaning in the modern festival

![]()

Chapter 10

A better life for more people

Jaqueline Tyrwhitt’s contribution to the festival of Britain – UK

Paola Zanotto

On 4 May 1951, The Festival of Britain opened its doors to the public and, in the end, over 8,500,000 people will visit the South Bank Centre, the centrepiece of the festival in London. But this was not the only location; exhibitions and fairs had been organised in several cities throughout Britain, with the common theme of showing British contributions to civilisation and progress in the past, present, and future. Nevertheless, London was the one affected most by the event. In fact, it was ‘transformed into a festival city’1 to lift the people’s morale after years of unparalleled austerity following the end of the Second World War.

Architectural and planning innovation played a special role in the festival. Not only in the production of memorable landmarks and innovative buildings that attracted the general public – as happened in other expos in the previous years – but also through exhibitions that highlighted new innovative construction techniques and the planning strategies underway after the destruction brought about by the war.

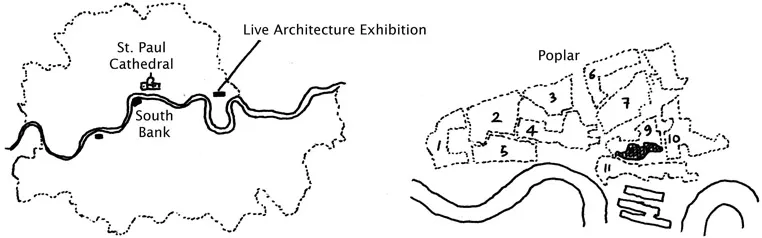

The festival in London gravitated around three main locations: the South Bank Centre near Waterloo, the Pleasure Gardens near Battersea, and the Live Architecture Exhibition in Poplar. The planning to celebrate the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition began in 1947, and the Poplar site was chosen in 1948. But it was only in a quite late stage of the festival’s organisation that a team was formed to design the Town Planning Pavilion – a temporary venue marking the entrance of the Live Architecture Exhibition. In January 1950, a woman was hired and became a member of the planning sub- committee formed to organise the material to be displayed: her name was Jaqueline Tyrwhitt. The daughter of an architect serving in the British colonies, she was very well-connected through her professional networks; she worked in different fields, among them town planning, architecture research and education, landscape architecture, and garden design. Tyrwhitt used her personal and professional networks during her life to bridge different disciplines and institutions. Her point of view in relation to the 1951 exhibition is particularly valuable considering that she was also deeply involved both in the long- term planning policies in Britain. She believed that any utopian vision must be underpinned by a pragmatic approach, describing the ideal town planner thus:

The planner… must have plenty of courage and tact and – above all – a practical imagination that enables him always to look just ahead and see a future pattern of richer life that is attainable, given the will to work towards it.2

Through experiences recorded in her personal documents it is possible to retrace the backstage of the exhibition that took place in the Town Planning Pavilion in the new neighbourhood in Poplar. The aim of this chapter is to explore the contents and the communication strategies developed by Tyrwhitt used to present planning and architecture principles at the Live Architecture Exhibition and the complex relationship it had with the Festival of Britain as a whole.

Work in progress: the national reconstruction campaign framed in the festival

The Festival of Britain was tailored to its historical context but its purpose and contents were particularly relevant to the reconstruction programme of the Labour Party governing at the time. Since the New Town Act of 1946 and the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 the modern planning system was established and finally regulated in the UK. The reconstruction campaign focused on the application of a planning principle initially published in 1930s America: the neighbourhood unit.

The two key tenets of the reconstruction were the foundation of new towns outside London’s Green Belt and the reconstruction of parts of the capital itself. These activities often involved the same people, and the planning principles applied were part of the same thinking: for example, Frederick Gibberd, the original creator of the Live Architecture Exhibition, had been the chief planner for Harlow New Town. Tyrwhitt had also been engaged in research about the neighbourhood unit and new towns since her studies in London (1924–35) and Berlin (1936–7). A great admirer of Patrick Geddes’ theories about regional planning, she worked on the inter-relationship between a city and its surrounding countryside, the sustainability of its food production, and the need for a civic core in newly planned neighbourhoods. Once back in the UK, Tyrwhitt had the chance to develop a project on the subject with the German sociologist Ruth Glass.3 Interested more in the social basis of the discipline rather than in the functional mechanisms of cities, in 1945 she organised a conference in cooperation with the RIBA architectural science board and the Institute of sociology entitled ‘Human Need in Planning: The Contribution of Social Studies to Architecture and Planning’. This title was later recalled by Tyrwhitt in one of the rooms of the Town Planning pavilion six years later.

The Town planning Pavilion and the Live Architecture Exhibition aimed to show, in fact, the latest innovation applicable in the national postwar reconstruction campaign. The East End site in Poplar was a fragment of a wider ongoing regeneration scheme of the whole area next to the docklands, named after the great Labour politician and journalist George Lansbury. The area had been heavily damaged after the air raids of the Second World War, and its redevelopment became a paradigm for the new housing needed in London and elsewhere. A large part of Poplar was going to be rebuilt as the Lansbury Estate through a series of self- contained neighbourhood units, and its realisation aimed to embody the kind of transformation that was possible for other towns and cities in Great Britain, and to be a catalyst for the reconstruction on a broader scale.

Figure 10.1 The Live Architecture Exhibition in black hatch, located in the wider Lansbury Regeneration Area. Author’s sketch.

The festival could serve to frame the work done so far and present a vision about the upcoming future of British cities in response to people’s growing skepticism, due in part to a fragmented and partial knowledge of the works in progress. There is no question that Tyrwhitt was aware of the political message the exhibition was expected to send because during the war she had been acting director of the School of Planning and Regional Reconstruction (SPRR), replacing E.A.A. Rowse, who was called to serve in the army.

Tyrwhitt’s main tasks during her time at the school included the coordination of a team for research surveys in preparation for town and country planning schemes, and the organisation of an ‘Army Education correspondence course’ for people keen to continue their studies or to get involved in post- war planning while they were enrolled in the army. In 1950, much of this work was published by the Association for Planning and Regional Reconstruction (APRR) – a branch of the SPRR – in a volume of the Town and Country Planning Textbook,4 edited by Tyrwhitt. This professional experience made her a perfect candidate to take part in the Town Planning Pavilion. Moreover, Tyrwhitt had demonstrated excellent communication and teaching skills: in 1945, whilst the war was moving towards its end, she was asked by the British Ministry of Information to give a lecture tour across Canada and the US about town planning and post- war reconstruction programmes in UK.5

Thus, along with the architect Jane Drew and the housing consultant Elizabeth Denby, Tyrwhitt managed to gain an important role in the national debate about rebuilding Britain in the male- dominated environment of planning, as well as in the festival organisation:

Conspicuously few women contributed to Festival organization: there were none on the Festival’s Executive Committee, Presentation Panel, Architecture and Planning Committee, or Science and Technology Committee.6

The role of architecture in the making of the festival

The Festival of Britain displayed the achievements made possible by historical progress in different fields of knowledge. This would seem in line with the international exhibitions in Europe and in the US in the previous years, but there was an element of popular folklore that justified the title of the event as festival. The event of 1951 in the UK had, in fact, the objective to reshape the cultural approach of the British public towards the contemporary age, its products, its art, and, of course, its built environment. Architecture, town planning, and scientific progress were less ideologically contentious than more politically sensitive subjects such as education and the welfare service.7 As a result, they were selected as disciplines that could engage the general audience and help the festival to gain popularity while presenting a physical and tangible sign of recovery from the war. Exhibitions have often been influential in town planning history, as pointed out by Robert Freestone and Marco Amati who suggest that ‘while often forgotten, the imagined urbanism on show in exhibitions were often footsteps to more permanent urban spaces’.8 This proved to be true during the golden era of exhibitions about planning and architecture, between the end of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries, in some cases these events triggered a real cultural shift in projecting the future evolution of cities. Exhibitions could have different targets and serve different purposes in the planning field, as demonstrated by the pioneers Patrick Geddes and Marcel Poëte, and Frédéric Le Play before them.9 Playing a role that goes beyond mere propaganda, the effective use of images contributes to the visual impact of exhibitions as communication tool used to introduce technical subjects to an often unprepared public. This was the aim of the Live Architecture Exhibition, with the addition of a further level of complexity: the principles had to be shown, but they also had to be demonstrated as scientifically valid solutions to the housing crisis; solutions that people could trust.

Due to the scale of the event, the organisation of the various exhibitions was developed by several agencies. Some bodies involved already existed – such as the Arts Council and the Central Office of Information – but some others were set-up specifically for the festival: for example, the Council for Science and Technology and the Council of Architecture, Town Planning, and Building Research (COA).

Tyrwhitt’s position within this organisation was not easy: she worked closely with the designers and the architects involved in the pavilion, mediating the brief and comments from the newly formed COA. But because the Lansbury Area was part of a wider and longer- term project, managed by the London County Council (LCC), the making of the Live Architecture Exhibition generated conflicts between the agendas of the two organisations. The COA had a precise construction timeline and target and employed architects outside the LCC to ensure a better quality and a special character for the new neighbourhood. At the same time the Lansbury Estate was LCC’s first post- war redevelopment programme, long before becoming part of the festival programme, and the general coordination of the site was still under the control of the LCC.

The exhibition targeted a wide range of subjects, including local authorities, which were under pressure to deliver new housing estates due to material shortages. They had mandate from the Housing Minister to build affordable houses as well as houses for the private market in a ratio of 4 to 1.10 Giving the fact that the vision for the re- provision of homes destroyed during the war was a key issue in the 1945 elections, during the festival the topic of ‘the house’ was featured in bot...