eBook - ePub

Art and Expressive Therapies within the Medical Model

Clinical Applications

This is a test

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Art and Expressive Therapies within the Medical Model

Clinical Applications

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Art and Expressive Therapies Within the Medical Model explores how to best collaborate across disciplines as art and expressive therapists continue to become increasingly prevalent within the medical community. This collection of diverse chapters from seasoned practitioners in the field introduces readers to art therapy interventions across a variety of artistic approaches, patient demographics, and medical contexts, while paying special attention to new approaches and innovative techniques. This is a cutting-edge resource that illustrates the current work of practitioners on a national and global level while providing a better understating of the integration of biopsychosocial approaches within art and expressive therapies practice.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Art and Expressive Therapies within the Medical Model by Deborah Elkis-Abuhoff, Morgan Gaydos, Deborah Elkis-Abuhoff, Morgan Gaydos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Histoire et théorie en psychologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Art Therapy in Pediatric Oncology

When a child becomes seriously ill, the whole family’s sense of well-being is shattered. Preventive medicine has nearly eradicated many causes of childhood mortality, leading most people to assume that all children will grow to adulthood. The diagnosis of a life-threatening illness unleashes a crisis: not only must the family find treatment to restore the child’s health, continue to care for siblings, and maintain careers to keep health insurance, but they must also work through profound questions—Why did this happen? How? Is it my fault? What does it mean to the rest of our lives? In the space of brokenness, the power of creativity emerges: Art therapy in pediatric oncology can offer immediate comfort, teach coping skills, and build resilience to help patients and families confront the crisis of illness. Approaching art therapy in pediatric oncology through the lens of the patient experience lends focus and impact to the profession.

What a Medical Diagnosis Means

A medical condition is not the only challenge patients face: becoming a patient can impose its own sense of powerlessness. One of the early reports on childhood cancer survivors includes a compelling description of what it is like to be a patient in a hospital. Being a patient is like visiting a foreign land: The patient is surrounded by a host of strange people, smells, clothing, language, food, behavior, and customs. From the lab-coat dress code to abbreviations for illnesses and procedures, many aspects of the hospital language are designed to exclude the uninitiated (patients and families) from the communications of what may seem like a secret society (medical staff) (van Eys, 1981). Patients and families may feel hospital culture lacks transparency, leading to difficulty trusting the medical team and feeling unnecessarily excluded from their care.

Coping with a serious illness is essentially a process of grief. Feelings of sadness and anger are natural human responses to loss, and a serious illness is a loss that must be mourned. The healthy, autonomous self is harmed by the illness, as well as the physical body. Art therapy offers patients powerful tools for allowing those feelings to emerge, find expression, and be heard—allowing the healthy, whole person to replace the passive ‘patient’ identity (Councill, 2012). Patients’ sense of competency and control are well served by the opportunity to tell their own stories, to invent personal symbols, to express feelings in metaphor, and to reflect on life experiences.

Especially with cancer, the outcome of treatment may only be known over time, and there is often little the patient can do other than to take medicine and wait. Art therapy puts the patient-artist in control—what kind of art to create, whether the product is ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ what it means, and whether it is to be saved or thrown away, are decisions that only the artist can make. That small measure of control can help patients step out of their isolation and fear.

Adjustment

Art can be adapted to any age and to almost any level of neurological and developmental functioning. Councill writes of her work with pediatric cancer patients, that,

offering familiar materials with the skilled therapist’s support can reassure the ill child that he or she is still a person with a great deal to offer … When a child is ill, words often fail, either because the child’s vocabulary does not match the experience or because the ill child feels he must protect the adults around him from his feelings.

(Councill, 2012, p. 228, referencing Bluebond-Langner, 1978)

Art therapy can open the door to metaphorical expression: A dragon made of clay can telegraph a child’s anger and confusion, but it can’t really hurt anyone. When symbolic artwork is accepted and understood, the child is also validated and encoded messages received.

Cognitive Development, Agency, and Resiliency

A medical diagnosis can affect one’s sense of self-esteem and efficacy, and impact cognitive and social development. Separated from daily routines of school, family, and friends, a child’s identity is challenged. Children have access to the full range of human emotions, but their ability to reason and understand the curative intent of treatment is determined by their age, cognitive development, and social support:

- Very young children sense that their parents are frightened, but they may not be able to understand why. They may try to be ‘good,’ so as not to further upset the family, and perceive treatment as a punishment for being ‘bad.’

- School-age children may grasp the seriousness of their illness, but focus on changes in their appearance, such as hair loss and weight gain, due to the side effects of chemotherapy, and missing out on school and friends.

- Teenagers and young adults often put their future on hold during treatment, and risk losing opportunities they worked hard to attain. They also give up much of their autonomy and accept care and supervision from parents and medical personnel. Anger and withdrawal are common coping strategies for ill teens and young adults. The question of blame, rooted in the magical thinking of early childhood, echoes throughout all stages of development as patients and parents alike wonder why this happened to them.

An individual case of childhood cancer is seldom the result of any identifiable cause, certainly not the result of anything the patient has done. Such a diagnosis can lead to a sense of hopelessness and depression because it seems that one’s actions do not matter. The social science concept of personal agency refers to the ability of an individual to influence his or her life circumstances by taking action. Explaining this concept, Bandura (1999) writes, “unless people believe that they can produce desired effects by their actions, they have little incentive to act or persevere in difficult circumstances” (p. 28). He continues, “those who believe they can relax, get engrossed in engaging activities, calm themselves by reassuring thought and support from friends, family, and others find unpleasant emotional states less aversive than those who feel helpless to relieve their emotional distress” (p. 30). Art therapy can help patients feel a renewed sense of agency by engaging them in processes that are both active and calming—allowing them to take small actions that can make enduring the illness and treatment more tolerable.

A Lesson in Agency

When I invited a 14-year-old boy to participate in the open art studio at the clinic where he received chemotherapy, he repeatedly refused. His main coping strategy seemed to be to isolate himself and ignore everything that was happening. One day when I invited him to the art table he angrily explained to me that he, personally, did not have cancer—only his body did—and that his ‘real’ self stayed at home while his body received treatment. He would not work with me because that would mean he would have to show up as a person, and he wasn’t going to do that. I responded that it must be hard work to divide himself in two like that, and if he ever changed his mind, he was always welcome. Over the next few weeks, he gradually sat closer to the art therapy space and conversed with those who participated; during the last month of treatment, he even led a group art project. As I reflected on that experience, I realized that for some patients participating in art therapy might exact a personal cost: that I was asking patients to allow their hearts, minds, and imaginations to join in their treatment, not just their physical bodies.

A Resilient Response

Though many people regress in the face of illness, cancer treatment may go on for months, and even years, calling on patients to develop new coping strategies to help them move forward in the face of uncertainty. Engaging in creative work at a developmentally appropriate level can be profoundly normalizing and can help young patients reflect on their experiences and explain to others what it is like to cope with a serious illness.

A college student diagnosed with an immature teratoma fell into a coma soon after diagnosis. Though she did not require chemotherapy after hospitalization, she visited the outpatient clinic often to participate in the art therapy open studio.

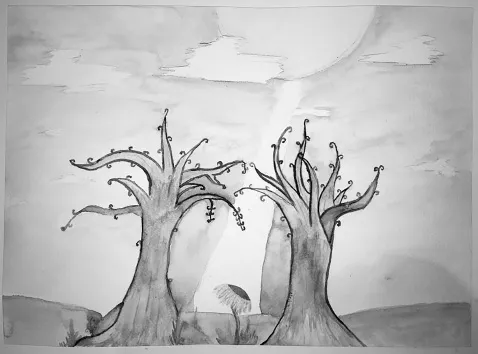

She was grateful to have a good prognosis and minimal treatment, but was still profoundly shaken by the experience. She related that her friends and family expected her to be happy and get back to normal, but she felt phony when she tried to agree with them. In a watercolor painting, she depicted herself as a sunflower sheltered between two trees, and concluded that she needed family and friends to give her room to reflect on all she had been through (Figure 1.1).

As the patient became a creator in art therapy, the helplessness she experienced while in a coma was replaced by resiliency and a sense of personal agency. Working creatively and being heard allowed her to give form to her feelings and needs, as she began the process of rejoining her former life of school and friends.

Figure 1.1 A Patient’s Reflection on Moving Forward After Treatment

Coping with Symptoms

Relieving, describing, and coping with symptoms are woven into the fabric of care for many people diagnosed with a serious illness. Fear of pain and distress over intrusion on body boundaries are common reactions to medical procedures, especially in children, who may have difficulty understanding the intent of the procedure. Patients with chronic illnesses often must deal not only with acute pain that signals a problem in need of treatment, but also with chronic pain that may be an ever-present part of life. Art therapy offers patients a proactive tool for coping with pain that is not fully relieved by medication and provides a way to gain mastery over frightening events (Councill et al., 2009).

Just as social isolation can exacerbate feelings of depression and hopelessness, a sense of belonging to a community can be a powerful source of support in recovery from trauma (Boss, Beaulieu, Weiling, Turner, & LaCruz, 2003). Illness may separate young people from ordinary activities that connect them to their community. Open studio art therapy in a treatment center brings patients together, creating opportunities to connect with others experiencing similar challenges.

Art Therapy and the Culture of Medicine

The power of art therapy is rooted in the combination of two inseparable elements: the creative process and the therapeutic alliance (Rubin, 1989, 2001). In medicine, a measured, targeted intervention causes a physical change to occur in the patient—an antibiotic clears an infection or a surgery repairs a broken bone.

Medical professionals follow treatment protocols with extreme precision under controlled conditions designed to achieve a desired outcome, but art therapy takes place in the ambiguous, messy, interpersonal side of life, and provides a complement to the precision of modern technology. It is within the witnessed creative process, and mutual reflection between client and therapist, that art therapy occurs. Being allowed to ‘get messy’ in the very clean hospital environment, and to engage in an open-ended creative process that doesn’t have to be ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ are among the gifts art therapy brings to hospitalized patients.

Art Therapy and the Medical Environment

One key difference between art therapy in mental health and art therapy in medicine is that most of the time medical patients do not have mental health diagnoses. Pediatric oncology patients are typically “normal children dealing with abnormal circumstances” (Councill, 1993, p. 78). They come to the hospital seeking treatment for a medical condition, not for psychotherapy, and it is important for the art therapist to teach patients and families how art therapy can help.

The building blocks of medical art therapy include psychology, neuroscience, the study of creativity, the relationship between the body and the mind, and the theory and practice of art therapy, which elucidates many approaches to the healing potential of the visual arts. Art therapists may support coping during active treatment, facilitate the transition from treatment to the end of treatment, or work with patients and families at the end of life.

Cancer and other serious medical conditions are so prevalent that it is likely the therapist or a member of her family may one day experience a serious illness. Especially when there is a cancer history in the therapist’s family, there may be less emotional distance between therapist and client. Managing one’s counter-transference is essential to practicing in medicine. Witnessing the daily suffering of children and adults can bring up feelings of hopelessness and burnout, but helping patients find hope and self-expression during suffering can be extremely rewarding.

Adaptive Models

A great deal of medical art therapy is done in settings that are not very private for the patient. In a clinic or infusion center, much of what is said and created is apparent to everyone in the area. In a hospital room, family members, visitors, and healthcare professionals must be included, excluded, or managed in some way before therapy can begin. The art therapist working at a patient’s bedside is essentially a guest in the patient’s home (Givens, 2008). Medical art therapists create a safe environment by teaching patients, family members, and healthcare providers to allow open-ended creative work without judging and questioning. Patience, humor, empathy, and humility give the medical art therapist the poise to teach patients, families, and hospita...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Editors

- Contributing Authors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Art Therapy in Pediatric Oncology

- 2 The Application of Technology Within the Medical Environment: Tablet, Apps, and Stylus

- 3 Working with Children Who Encounter Medical Challenges: A Multimodal Approach

- 4 The Use of Magic Therapy for Children with Hemiplegia

- 5 Photography as a Natural Therapeutic Process for Medically Ill Patients

- 6 Eating Disorders and the Medical Necessity of Collaborative Care

- 7 Visual Narratives as an Art Therapy Treatment in Cancer Care

- 8 Storytelling with Expressive Arts Therapy: Medical Therapeutic Work with Individuals

- 9 Medical Dance/Movement Therapy for Chronic Conditions: An Overview of Important Outcomes

- 10 Art Therapy and Tourette Syndrome: Utilizing Guided Imagery and Chakra Exploration

- 11 Engaging Those with Parkinson’s Disease in Group Clay Manipulation Art Therapy

- 12 Art Therapy and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- 13 Recovery from Grief and Pain: Results from an Art Therapy Relational Neuroscience Four-Drawing Art Therapy Trauma and Resiliency Protocol

- 14 Exploring the Impact of Art Therapy with Stroke Recovery

- 15 Art Therapy in the Detoxification Phase of Treatment of Substance Use Disorders

- 16 Art Therapy Applications and Substance Abuse

- 17 Material Considerations to Providing Art Therapy Within a Medical Model

- 18 TTAP Method® Applied to Individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease

- 19 The Use of Clinical Assessments Within Medical Art Therapy: Identifying the Level of Emotional and Physical Symptoms

- 20 Culturally Responsive Care for Art Therapists in Medical Settings

- 21 Special Issues for the Art Therapist Working in a Medical Setting

- Index