eBook - ePub

Memory and Mind

A Festschrift for Gordon H. Bower

This is a test

- 680 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A comprehensive overview of the current state of research on memory and mind, this book captures the career and influence of Gordon H. Bower (as told by 22 of his students and colleagues), showing how Bower's research and mentoring of students has broadly and deeply affected modern research. In addition to many personal reminisces about Bower's res

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Memory and Mind by Mark A. Gluck,John R. Anderson,Stephen M. Kosslyn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Histoire et théorie en psychologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter

1

Gordon H. Bower:

His Life and Times

His Life and Times

My contribution to the celebration of Gordon Bower’s 75th birthday by means of this volume is this memoir on his research career and its context. I plan not to dwell on reminiscences (although, see Box), but, rather, to look forward, seeking to detect trends dating from the mid-1900s that will lead to the events of the 2000s. Because of the incredible scope of Gordon Bower’s contributions to psychology, the task calls for what is now popularly known as a team approach, and I concentrate on two issues that motivated much of the theoretically oriented research on learning, broadly defined, during the 1900s—

Is a theory of human learning possible?

How many kinds of learning exist?

and the role of Gordon Bower in progressing toward their resolution. I conclude with a characterization of his influence on a large, and still growing, network of investigators.

Is a Theory of Human Learning Possible?

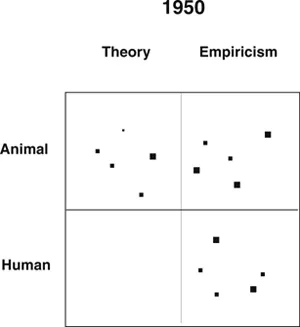

The answer to this question may seem obvious to sophisticates of the present era, although the same was far from the case when I was introduced to psychology in the 1940s, as represented (imaginatively) in Figure 1–1. Frequencies of plotted points in the four quadrants of Figure 1–1 index my impressions of the relative sizes of the existing literatures of the four kinds as of 1950 and sizes of the entries reflect the contributions of individual investigators. Awareness of the blank cell in the lower left quadrant of Figure 1–1 by a young investigator with a theoretical bent appeared to confine him to a career of studying rats in mazes or Skinner boxes.

Figure 1–1. State of human versus animal learning theory in 1950. Cell entries represent investigators, contributions being roughly proportional to magnitudes.

Learning theory was a hot topic, but it was the learning theory of an almost closed aristocracy. The leaders were the senior “classical” systematists: Guthrie (1940, 1942), Hull (1937, 1943), Skinner, 1938, and Tolman (1932, 1951). The empirical basis was entirely derived from research on lower animals.

In sharp contrast, the psychology of human learning was a search for empirical generalizations without reference to classical learning theory. The search was typified by the decades-long series of contributions on conditions of learning and forgetting by L. Postman (Postman, 1962, 1976) and B. J. Underwood (1957, 1964). The spirit of this period was epitomized and the body of accumulated facts about human learning was summarized in its leading textbook (McGeoch, 1942; McGeoch & Irion, 1952).

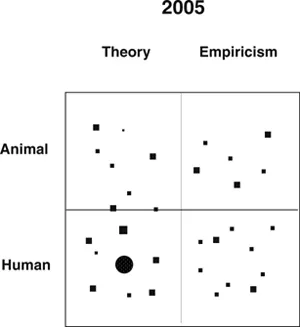

The overall theoretical landscape illustrated in Figure 1–1 was drastically changed within a relatively few years to that in Figure 1–2 largely by the efforts of Gordon Bower and his associates the largest entry representing the contributions of Gordon Bower.

Figure 1–2. State of human versus animal learning theory in 2005, the largest entry representing the contributions of Gordon Bower.

In the mid-1900s, theories of human learning with any semblance of formal structure had yet to appear; hence the vacant lower left-hand quadrant in Figure 1–1. But by the early 2000s, the formerly empty quadrant contained many new entries, revolving around the very large one (representing Gordon Bower, of course) like planets around the sun (Fig. 1–2). One of the larger “planets” signifies the appearance of the first textbook of mathematical learning theory, Atkinson, Bower, and Crothers’s An Introduction to Mathematical Learning Theory (1965), henceforth ABC. Among Bower’s contributions to ABC, he produced striking examples of mathematical learning theory applied to data obtained from human subjects. One, drawn from work presented in Bower (1961), is a demonstration of the seemingly endless aspects of a set of data that can be predicted by a simple mathematical model with a single free parameter. The experiment was on paired-associate learning with the standard anticipation procedure. Stimuli were common English words and the responses were digits, for example, fox–3. Training was given to a criterion of correct responding. The single parameter c, probability of learning on any precriterion trial, was estimated by the formula

mean total errors = (1 – 1/N)/c,

where N denotes number of observations entering into the mean. All of the remaining entries in Table 1–1 (and many more) were predicted by the model.

Table 1–1

Predictions of Performance by a Model (Shades of ABC; Credit to Gordon Bower)

Predictions of Performance by a Model (Shades of ABC; Credit to Gordon Bower)

| Statistic | Observed | Predicted |

| Total errors | ||

| M | 1.45 | — |

| SD | 1.37 | 1.74 |

| Errors before 1st success | ||

| M | .78 | .75 |

| SD | 1.08 | .98 |

| Trial of last error | ||

| M | 2.33 | 2.18 |

| SD | 2.47 | 2.40 |

| Number of error runs | .97 | .97 |

| Alternations | 1.43 | 1.45 |

Note. ABC = Atkinson, Bower, and Crothers (1965)

These findings were amplified and extended by Bower (1961, 1962, 1967) and Trabasso and Bower (1964).

Once the wall between experimental analysis and formal theory of human learning had been breached by Bower and his associates, it appeared that every experimenter was ready to take on also the role of theorist. Thus some of the “planets” in the lower left quadrant of Figure 1–2 represent combinations of experimental research and theory on attention in learning (Kruschke, 1992; Restle, 1955; Trabasso & Bower, 1968), probability learning (Estes 1964; Myers, 1976), and categorization (Estes, 1986; Medin & Schaffer, 1978; Nosofsky, 1984).

Two of the “planets” in the left-hand quadrants of Figure 1–2 deserve closer attention because of a special relationship. The one in the upper left represents the most broadly influential quantitative model of animal conditioning and learning from the early 1970s to the present, that of Rescorla and Wagner (1972). The counterpart in the lower left dropped in out of the blue in the late 1980s; it represents a strikingly successful application of the formal conditioning mechanism of Rescorla and Wagner (1972) to human category learning by Gluck and Bower (1988a, 1998b).

The significance of this development lies in its implications for themes that may play leading roles in the 2000s. The stage was set for these by findings of Knowlton, Squire, and Gluck (1994) that effects of hippocampal damage appear only late in learning of a categorization task by amnesic patients. A follow-up by Gluck, Oliver, and Myers (1996) showed that this late-training deficit is predictable by Gluck and Myers’s (1993) interpretation of hippocampal function. Thus it appears that models arising in the work of Gordon Bower and his associates are having continuing and perhaps expanding roles in the research of the 2000s as they are applied with close attention to stages of learning in both animal and human subjects, to differences between patient populations, and to connections of psychological with neural theory.

How Many Kinds of Learning?

This question was first raised in a research context by Edward L. Thorndike in his distinction between “associative shifting” and “trial-and-error learning” (Thorndike, 1913), but interest among psychologists of learning lapsed until revived in a new theoretical framework by Hilgard and Marquis (1940). Cutting across research and theory on animal and human learning, this question was undoubtedly the one most widely debated in the literature of some four decades from the appearance of the first formal single-factor theory (Hull, 1937, 1943) to the sweeping review by Bower and Hilgard (1981).

The preoccupation with kinds of learning appears to have originated as a reaction to Clark L. Hull’s strenuous development and defense of what seemed to most of his contemporaries as a radical proposal: Despite almost unlimited variety in empirical “laws” and minitheories of learning, all could, in principle, be derived from a single unified set of axioms, which he explicated in Hull (1943). The modal view of other theorists of learning for a period of some 40 years following Hull’s proposal was a consensus on two basic kinds of learning (Bower and Hilgard, 1981).

The two kinds have been defined in different ways, but I limit consideration to grouping by (a) experimental procedures and associated empirical phenomena; (b) underlying cognitive processes; and (c) neural bases or correlates of learning:

- Grouping by procedures and phenomena was first treated systematically by Hilgard and Marquis (1940), whose review has been successively updated and amplified by Kimble (1961) and Bower and Hilgard (1981). A condensed summary abstracted from these reviews that illustrates the major prevailing theme is given in Table 1–2. Bower and Hilgard seemed to view choice among these binary categorizations as largely a matter of convenience and, in fact, at the conclusion of their review expressed sympathy for Hull’s perspective (see also Perkins, 1955; Terrace, 1973). Table 1–2

Dichotomies of Learning, “The Standard Theory” after Kimble (1961)Authors First Type Second Type Hilgard & Marquis, 1940 Classical Instrumental Konorski & Miller, 1937 Type I Type II Mowrer, 1956 Conditioning Problem Solving Schlosberg, 1937 Conditioning Success learning Skinner, 1937 Respondent Operant - Grouping of kinds of learning associated with inferred underlying processes is well illustrated by the work of Gordon Bower and his associates in the 1960s. As was detailed in a preceding section, Gordon Bower’s first published presentation of a model for paired-associate learning surprised many of his contemporaries with the assumption that such learning proceeds by abrupt all-or-none (henceforth A-O-N) jumps between unlearned and learned states. An assumption with a very long tradition in learning theory was that, in contrast, simple learning should be represented as a growthlike process in which a learner proceeds from an unlearned to a learned state by small, progressive increments (Bush & Mosteller, 1955; Hull, 1943). In Table 1–3, I compare predictions of paired-associate data by Bower’s single-parameter A-O-N model with predictions by a single-parameter incremental model—the “linear model” of Bush and Mosteller (1955), based on analyses presented in ABC, chapter 3. These results, strongly favoring the A-O-N model, are typical of many accumulated by Bower and his associates that point up the fruitfulness of recognizing A-O-N and incremental learning as two basic kinds of learning, defined at the level of unde...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Gordon H. Bower: His Life and Times

- 2. Memory From the Outside, Memory From the Inside

- 3. On the Law of Primacy

- 4. Gordon and Me

- 5. Toward Valued Human Expertise

- 6. The Algebraic Brain

- 7. Remembering Images

- 8. Sharing Landmarks and Paths

- 9. Evidence of All-or-None Learning From a Repetition Detection Task

- 10. Relations in Semantic Memory:Still Puzzling After All These Years

- 11. Using Cognitive Theory to Reconceptualize College Admissions Testing

- 12. Moving Cognition

- 13. Imaginary Worlds

- 14. Continuing Themes in the Study of Human Knowledge: Associations, Imagery, Propositions, and Situations

- 15. Category Learning: Learning to Access and Use Relevant Knowledge

- 16. Mood and Memory at 25: Revisiting the Idea of Mood Mediation in Drug-Dependent and Place-Dependent Memory

- 17. Affect, Cognition, and Social Behavior:The Effects of Mood on Memory, Social Judgments, and Social Interaction

- 18. Behavioral and Neural Correlates of Error Correction in Classical Conditioning and Human Category Learning

- 19. Category Learning as Schema Induction

- 20. Categorization, Recognition, and Unsupervised Learning

- 21. Updating Beliefs With Causal Models:Violations of Screening Off

- 22. Spatial Situation Models and Narrative Comprehension

- Author Index

- Subject Index