- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

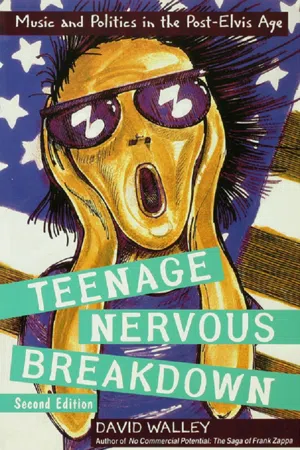

Teenage Nervous Breakdown

About this book

Teenage Nervous Breakdown: Music and Politics in the Post-Elvis Era combines music and cultural history and criticism to examine how rock and the rock lifestyle have been merchandised first to a teenage audience and eventually to a worldwide consumer society. Well-known, iconoclastic writer/ critic David Walley examines the entire rock culture and

Information

Chapter 1

“This, Here, Soon”1

Growing Up

it’s like the high dive at camp

you went up one way

and you came down another

you could either dive or jump

but you couldn’t go back down the ladder,

some kids stood there

all thru lunch

but the counselor

wouldn’t let them climb down

and the longer you waited

the harder it got.

I did one of those life saving jumps

the kind with my arms and legs spread

but I still splat the water pretty hard it stung.

—Peggy Garrison2

The younger generation begins in the womb; before it is three years old, major industries … are vying for its favor. By the time it is in its teens, its purchasing power is immense; and it has by then developed a social style of its own, which older generations react to, chiefly with aversion but to some extent with emulation.

—Gilman Ostrander3

In the Post-Elvis Age our collective perception of our history as a people and the cultural time of our nation have been fundamentally altered. Both have been held hostage by the corrosive effects of an increasingly celebrity-driven consumerism, itself the result of the cumulative effects of the commercial exploitation of high school peer group dynamics that started in the fifties, whose present market share has, as of this writing, been computed to be a whopping $65 billion per annum. During and after the Age of Elvis, this virulent form of goods-driven, not to mention intellectual, consumerism animated by the rock and roll beat has in turn affected our world to the point where a multinational corporate consciousness has replaced our sense of selves. In a little more than a quarter century, these marketing techniques now sell all manner of goods and services, its reach further extended by music television, which broadcasts its visual equivalent 24 hours a day, 7 days a week—our new Voice of America.

In those epochal years from 1954 to 1977 in which Elvis Presley’s and the Beatles’ careers bloomed and sputtered, rock and roll had succeeded in transforming our collective character. By the early sixties, adolescence, an uncomfortable waystation on the way to maturity—formerly a matter of age or attitude—had become not only a big business, an infinitely renewable commercial resource, but also a desirable state of being all by itself. At one time it may have been that all you needed was love, but now a credit card or two is more than helpful to pay for the rock and roll dreams that money can buy. Today the economic power of youth has become the principal fuel that powers the great multinational entertainment conglomerates to an extent that even a decade ago was impossible to conceive. This state of affairs didn’t happen overnight. These tendencies have been inherent in America’s character from its inception—we’ve just ignored them.

In 1835 when Alexis de Tocqueville, a French aristocrat, wrote Democracy in America, he was fascinated by the vitality of a young America and its drive to be a great independent commercial power, although he had some reservations about that goods-oriented now. He did not question America’s being, its commercial spirit, but he was struck by what it could become as a result:

… not that it leads men away from the pursuit of forbidden enjoyments, but that it absorbs them wholly in quest of those which are allowed. By these means, a bind of virtuous materialism may ultimately be established in the world which would not corrupt, but enervate, the soul, and noiselessly unbend the springs of action.4

Two decades later while roaming the streets of Brooklyn and Jersey City, Walt Whitman, enamored, enraptured, and lyrically drunk on the fumes of American possibilities, wrote Democratic Vistas. Like de Tocqueville, he was aware of his nation’s now, but still held a consciousness of then, of America’s immediate past in the age of steam and rails, as well as of its immediate future in the Civil War and the era of the robber barons to come. He faced toward the future that he saw from the vantage point of his epochal poetic now:

America, betaking herself to formative action (as it is about time for more solid achievement, and less windy promise), must, for her purposes, cease to recognize a theory of character grown of feudal aristocracies, or form’d by merely literary standards, or from any ultramarine, full-dress formulas of culture, polish, caste, &c., enough, and must sternly promulgate her new standard, yet old enough, and accepting the old, the perennial elements, and combining them into groups, unities, appropriate to the modern, the democratic, the west, and to the practical occasions and needs of our own cities, and of the agricultural regions.5

Quite obviously, Whitman’s Democratic Vistas, his speculations, never envisioned multinational conglomerates built upon the commercial possibilities of adolescent consumers becoming bigger ones with more expensive tastes. Or the economies built upon educating preteen and preschool consumers how to step logically from Power Ranger/Ninja Turtle battle-axes to Air Jordans to BMWs in their own consumer-affinity groupings. Who knows what he would have made of the debate that has raged for a quarter century about the cumulative effect on children of sex and violence on TV or in movies? How would he have assessed the advertisers who sponsor and package such shows or the commercials themselves? Or the corrosive effects of commercials on the national mind and on the youth who spend a total of two months of waking hours per year alone watching them?6 Yes, these are modern problems for the modern age that Whitman couldn’t have foreseen. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that, despite this apparent weakness of vision to our modern sensibility, he intuited the path America had taken as well as the crisis it would provoke down the road:

I say of this tremendous and dominant play of solely materialistic bearings upon current life in the United States, with the result as already seen, accumulating, and reaching far into the future, that they must either be confronted and met by at least an equally subtle and tremendous force-infusion of purposes of spiritualization, for the pure conscience, for genuine aesthetics, and for absolute and primal manliness and womanliness—otherwise our modern civilization, with all its improvements, is in vain, and we are on the road to a destiny, a status, equivalent, in this real world, to that of the fabled damned.7

Fate of the “fabled damned”? That’s one hell of a punishment for straying from the idealistic ethical path he envisioned America should and could follow. But without a map-building childhood or an adolescence free from external commercial manipulation, what other course is available? What you see is what you get now, because America’s greatest industry, its major export to the world, is devoted to making products mediated on the now-ness of a promised collective mythical future that aims to negate the then of the past forever, just as our rock and roll world does.

In the roaring twenties, 60 years after Whitman’s Vistas, Johan Huizinga, the renowned Dutch medievalist historian, arrived on these shores to an America booming in the aftermath of World War I, a war that had plunged everyone into a bloody, pointless, and destructive frame of now—in the words of Ezra Pound, “For an old bitch gone in the teeth/For a botched civilization.”8 Like Whitman and de Tocqueville before him, Huizinga was also impressed by the force of America’s militant present-tense living. In a series of collected lectures and observations entitled America: A Dutch Historian’s Vision, From Afar and Near, he summarized the American experience of “This, Here, Soon” as indicative of its enthusiastic acceptance of life in the present and future tense.

And like de Tocqueville and Whitman, he saw that despite its commercial and social energy, there was also another force working on the spirit of America:

… a perpetual tension in America between a passionate idealism and an unrestrainable energy directed to material things. And because the popular mind in America is naive and easily moved emotionally, it often does not observe the contradiction between what the country does and its resounding democratic ideals.9

Although the Great Depression of the thirties may have briefly administered a shock to America’s consumer appetite, the shock did not last; the industrial boom generated by World War II and its aftermath rocketed America into an unparalleled material prosperity. For some at the dawn of the modern consumer era in the late forties, notably clergymen and scholars like Joseph Haroun-tunian, there was a profound and disquieting moral crisis afoot amidst this explosive, unnatural, and surreal abundance that

… tempts men to be at once fascinated and repelled by the good. It tempts men to pursue goods, and in doing so, to fear the good. The good is in “justice, mercy, and peace.” It is consistency and integrity, in loving according to truth and right. It inheres in men and not in things. It is other than the goodness of goods and without it, goods are not good. But the machine-made spirit teaches otherwise. It identifies the good with goods and induces men to dread it except as thus identified. It persuades men that there is no good other than goods. Thus men come to dread good as evil and to love evil as good. Thus it is that an apparent good produces evil.10

Harountunian’s dire remarks may have well suited certain segments of the population to whom consumer culture was still a novelty (and some today), but nearly a half century later, after the Pill, credit cards, microchips, and the Internet, his lofty homiletics seem quaint and arcane to the majority of Americans. For them, the Depression and World War II are as so much black-and-white film footage. And although the machine-made world in which we easily abide is deemed user-friendly, more than ever America’s watchwords remain “This, Here, Soon.”

Morality in a consumer society? Get real: Goods are goods, they’re morally neutral, some are better or worse, and about the only time the question comes up is just about the time you’ve paid for your car or the warranty has expired and it dies (how do they do that?). Only then do you find out that these days “durable goods” are by definition only supposed to last 3 years. If anything, moral rights have become consumer rights—all we need are tighter lemon laws since everyone’s a consumer, no? That’s the way we’ve all been schooled, and that goes to the heart of the matter, as we’ll find out.

But despite the fact that our playroom remains continually stocked with an inexhaustible surfeit of goods, there is an undercurrent of discontent, a notion of consequences that comes from the selective art of consumer forget. What do we do when we tire of our goods, our toys? According to Bill Bryson, former expatriate American journalist living in England, we banish them and the then they represent to the perennial garage, attic, or hall closet

… [which] seem to be always full of yesterday’s enthusiasms: golf clubs, scuba diving equipment, tennis rackets, exercise machines, tape recorders, darkroom equipment, objects that once excited their owner and then were replaced by other objects even more shiny and exciting. That is the great seductive thing about America—the people always get what they want, right now, whether it is good for them or not. There is something deeply worrying, and awesomely irresponsible, about this endless self-gratification, this constant appeal to the baser instincts.11

Though the nows of de Tocqueville and Bryson are separated by more than 150 years, their observations neatly dovetail into each other. The problem they uncover deep within the collective American psyche has come to a critical juncture, this result of living without the presence of a past. In Whitman’s time it was common to complain that, compared to Europe, America had no past and no culture of its own. It did; it just wasn’t on the order of Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe—it was different, uniquely American, and Longfellow wrote Hiawatha in the attempt to fill that void, as did James Fenimore Cooper with The Deerslayer. In this Post-Elvis Age, TV, computers, and rock and roll music are supposed to be equivalents, but what do they say?

Back in the fifties, at the dawn of the modern era of TV, Ernie Kovacs, one of the pioneers in electronically enhanced TV comedy, was quoted as saying, “Don’t watch too much TV, it will only rot your mind.”12 He may have been right, but that’s not all it’s done. While today Ernie Kovacs is hailed for the creation and development of a unique comedic electronic visual vocabulary, he was looked on in his time as a lovable if quirky eccentric. An exception in the so-called Golden Age of Television, he managed to succeed despite, not because of, the possibilities already inherent in the intoxicating mixture of commerce and entertainment. TV exerted its fascination not only on adult Americans of the post-war generation who were comparatively new to it, but also on a bumper crop of children. For preschoolers in the fifties, it was an electronic babysitter to give Mom a break, and when the older school-age children trooped in after school it served as company so that the evening meal could be prepared and on the table at 5:30 when Dad came home. Such diversions included not only Romper Room or Kukla, Fran, and Ollie in the morning but also after-school teen dance shows like Dick Clark’s American Bandstand (and its regional equivalents), which publicized the music of Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and others. Wildly successful of course were Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse Club and The Wonderful World of Disney, which in 1955 launched not only a theme-park way of life and national merchandizing fads but also a media conglomerate lifestyle/ideology of considerable economic and cultural strength that still exists today. During this “Golden Age” an enduring connection was cemented between Mickey Mouse and rock and roll (more on that later), through which merchandizing techniques were developed and refined that would appeal to teenagers and future generations of teenagers as well.

According to Steven Kline, a Canadian media researcher, in his book Out of the Garden: Toys and Children’s Culture in the Age of TV Marketing, it was in the service of the economic goals of Ronald Reagan’s America that in the early eighties the children’s TV industry was deregulated so that toy manufacturers were given free rein to produce half-hour cartoon infomercials to sell their character toys to preschoolers and preteens. Ever the economic realist. Reagan was just leveling the playing field by expanding the reach of merchandizing practices already in place in the early fifties that had been dealing with young teen baby boomers and their uncommitted money, which now could ensnare preteens and toddlers in a market that was formerly off limits. Preteens are no longer considered passive; their “lifestyle preferences” are not only actively solicited and tracked, but it’s also commonplace these days for kids themselves to be consultants and junior art directors for toy companies.

Enough time has passed since the fifties, so there’s a closed feedback loop operating under these unifying premises: Habituate children early to the values of the broker’s world even though they might not immediately have the direct purchasing power, for eventually when they become teens they’ll demand their own goods just like their sisters, brothers, and parents before them. Finally it was possible for younger and younger children to be exploited by larger and larger industries for, as it turns out, bigger and bigger bucks. In the twenty-first century, this seems to be an acceptable situation despite the consequences it has on all of us of whatever age. It’s an ironic comment on American life that if you want to find out about c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to the First Edition

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1. “This, Here, Soon”

- Chapter 2. Who Stole the Bomp (from the Bomp Sha Bomp)?

- Chapter 3. Blame It on the Sixties

- Chapter 4. Boxers or Briefs? Music Politics in the Post-Elvis Age

- Chapter 5. Play School: You Can Dress for It, but You Can’t Escape It

- Chapter 6. The Twinkie Defense

- Chapter 7. Bad Day at Internet

- Chapter 8. Asking Alice: Fighting for the Right to Party

- Chapter 9. Don’t Touch Me There: Whatever Happened to Foreplay?

- Chapter 10. White Punks on Dope: Why Camille Paglia Is Academe’s Answer to Betty Page

- Da Capo

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Teenage Nervous Breakdown by David Walley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.