eBook - ePub

One Hundred Case Studies in Epilepsy

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

One Hundred Case Studies in Epilepsy

About this book

From pediatric to the elderly, from contractible to refractive, epilepsy is an illness that manifests in many forms and across a range of demographics. In this fascinating volume, the author details more than one hundred instances where health care practitioners faced unusual challenges in treating the disease. All aspects of epilepsy are explored

Information

II INTRIGUING CAUSES AND CIRCUMSTANCES

Case 20 ABNORMAL HEART RATE IN A CHILD WITH WEST SYNDROME

Julio Ardura and Jesus Andres

History

We evaluated a full-term (38 weeks of gestational age) newborn male. His mother was healthy. During prenatal monitoring, both bradycardia and late-onset decelerations were observed in the fetus. After delivery, the physical examination showed normal intrauterine growth. Apgar scores were 3/7; and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was required.

On the 3rd day of post natal life, episodes of body hyperextension and abnormal eye movements were observed. On day 11, generalized tonic-clonic convulsions occurred.

Examination and investigations

In the newborn period, the blood glucose level was 30 mg/100 ml. Blood cultures as well as a serological screening of congenital infections (toxoplasmosis, other infections, rubella, cytomegalovirus infection, herpes simplex virus infection –‘TORCH’) and syphilis were negative. An EEG performed 23 days after birth showed bursts of spikes in the right parietal region. A second EEG performed at the age of 3 months demonstrated a hypsarrhythmic pattern. Brain ultrasound performed on day 5 after birth showed right ventricular dilatation, and subependymal and intraventricular haemorrage. A CT scan at the 17th day of life revealed enlargement of the right lateral ventricle, and subcortical parieto-occipital atrophy.

Continuous 24-hour, polygraphic continuous recordings of heart rate were performed on days 1 (first day of life), 15, 57, 289 and 295. Data analysis was carried out using the single cosinor method, which is a statistical test for chronobiological rhythms.

Heart rate analysis disclosed no circadian rhythm at any time during this follow-up period (Table 20.1). Significant ultradian rhythms occurred within a period of 8 hours on day 1 and within a period of 4 hours on day 289.

Table 20.1 24-hour heart rate rhythm cosine parameters

Diagnoses

West Syndrome, birth asphyxia, cerebral hemorrhage, subcortical atrophy and seizures. Circadian disturbances of heart rate.

Treatment and outcome

Phenobarbital was initiated at a total daily dose of 60 mg (20 mg/kg). Because seizures continued, phenytoin was added (initially at a daily dose of 7mg/kg and subsequently at 10 mg/kg). The convulsions were finally controlled with a combination of clonazepam (0.5 mg twice daily), phenytoin and phenobarbital.

When the baby was last examined at the age of 3 months, episodes of generalized flexor spasms as well as a delay in developmental milestones were noted.

Commentary

Epilepsy influences the biological rhythms of melatonin, sleep/wake and other hormones. Nevertheless, few papers have been published dealing with the study of biological rhythms in children with seizures.

We describe the patterns of circadian and ultradian heart rate rhythms during a 10-month follow-up in one case of West Syndrome. Circadian heart rate variability, which is not mature in newborn infants, usually appears at 30 days of age, continues through the 2nd and 3rd months of life, and remains throughout life. Therefore, in our patient, circadian changes of heart rate rhythm were expected to occur at least by the latest recording (day 295). Nevertheless, our patient’s heart rate showed no evidence of circadian rhythms during any of the recordings.

On the other hand, healthy infants have ultradian high frequency heart rate rhythms (3-hour) at birth, and low frequency rhythms at 90 days of age. In this case, the ultradian rhythms were less prevalent, and high frequency rhythms were predominant during the entire follow-up period.

What did we learn from this case?

We surmised that the absence of circadian rhythms in this patient could be accounted for by damage to his central nervous system (CNS) and speculate that this phenomenon may occur more often than is believed because it is generally not investigated in this syndrome.

In addition, we suspect that the appearance of biological rhythms in the postnatal period and during infancy may prove to be a useful indicator of normal maturation of CNS structures. On the other hand, the absence or delay of their appearance during infancy might indicate a disturbance of the CNS. Thus, circadian rhythm of heart rate might be an indirect measure of the degree of biological derangement.

How did this case alter our approach to the care and treatment of our epilepsy patients?

Based on this case, we believe that West syndrome may alter circadian rhythms permanently and modify the appearance and predominance pattern of ultradian rhythms of heart rate variability.

In our opinion, monitoring biological rhythms could be helpful in gauging the degree to which CNS structures are mature in patients with West Syndrome and, quite possibly, in patients with other neurological conditions. We do believe this issue is worthy of further study and have incorporated circadian heart rate analysis as well as the measurement of other biological rhythms in our ongoing clinical studies to further elucidate their significance.

References

1. Ardura J, Andres J, Aldana J, Revilla MA, Aragon MP. Heart rate biorhythm changes during the first three months of life. Biol Neonate, 1997;72:94–101.

2. Bloom FE. Breakthroughs 1998. Science 1998;282:2193.

3. Nelson W, Tong YL, Lee JK, Halberg F. Methods for cosinor-rhythmometry. Chronobiologia 1997;6:305–25.

Case 21 HYPERACTIVE BEHAVIOUR ATTENTIONAL DEFICIT IN A 7-YEAR-OLD BOY WITH MYOCLONIC JERKS

Johan Arends, Albert P Aldenkamp and Biene Weber

History

A 7-year-old boy was referred to our child neurological programme for learning disabilities with complaints about hyperactive behaviour, attention deficit, lack of concentration and unexplained fluctuations in school performance. Moreover, short periods (lasting some seconds) of sudden change of alertness were reported; the change in alertness was accompanied by loss of function. These short episodes occurred both at school and at home, mostly when the boy was watching television or playing computer games. There was no amnesia for these events or change of facial colour, but sometimes there were stereotyped movements. Most of these events were interpreted as symptoms of the attention-deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and the movements were interpreted as ‘tics’.

Hyperactive behaviour had started at a very young age and did not respond to treatment (e.g. with methylphenidate). After starting in regular education, the boy had been referred to special education because of the hyperactive behaviour, combined with conduct disorders. Psychomotor development was normal, although language development was delayed.

Examination and investigations

Neurological examination was normal. The patient was right-handed.

EEG showed normal background activity with frequent multifocal (poly)spike–waves (occurring six times in each 10 seconds). These waves were sometimes localized frontally and at other times they were generalized. During the recording, eight short seizures combined with epileptiform discharges were observed; these occurred only when the patient was watching television and they were accompanied by jerks. There was no specific photosensitivity to light stimuli, but there may have been sensitivity to specific patterns (such as the red colours on the television screen).

Neuropsychological investigation showed subnormal intelligence (Wechsler full-scale IQ was 56), with corresponding verbal and performance scores (verbal IQ was 62 and performance IQ was 54). Beery tests for psychomotor development showed a psychomotor delay of about 3 years, a delay in language development, and symptoms of ADHD (especially attentional deficits and hyperactive behaviour) and conduct disorders. There was evidence that the ADHD is a secondary symptom. During several periods, the sudden drops in alertness were observed. After such episodes, the symptoms of ADHD increased.

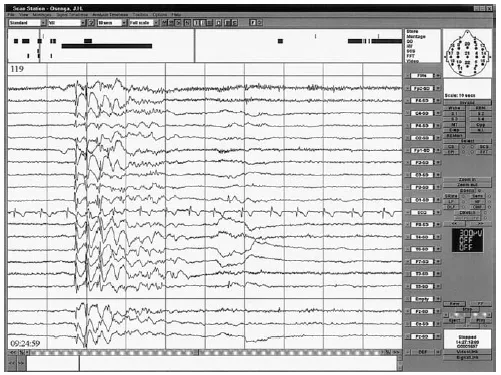

EEG combined with neuropsychological assessment showed frequent multifocal epileptiform discharges of sharp waves, spike–waves and polyspike–waves. During this period, frequent myoclonic jerks were observed (74 jerks in a recording that lasted 30 minutes). These jerks especially involved the shoulders (the left and right shoulders independently) with hypertonia. In addition there were infrequent absence seizures (four were recorded in ½ hour). The myoclonic jerks were most pronounced when the patient was watching television, but they were also present during absences seizures when he was not watching television. The myoclonic absences interfered significantly with cognitive function such that the patient did not react to questions during the myoclonic seizure and did not remember being questioned after the seizure. Simultaneously with these seizures the EEG showed generalized discharges with spike–waves and polyspike–waves over a period of 5–13 seconds; there was also sometimes localized activity of frontal origin. In addition, photosensitivity for patterns and bright colours was established. This was accompanied by self-induction. The patient reported feeling a pleasant sensation in his head during the seizures. Figure 21.1 shows a sample of the EEG discharges during the myoclonic absence seizures.

Magnetic resonance imaging scanning showed no abnormalities.

Diagnosis

Myoclonic absence epilepsy1 with developmental delay and secondary ADHD symptoms with conduct disorders.

Treatment and outcome

Some antiepileptic drugs (e.g. carbamazepine, phenytoin, vigabatrin, gabapentin) may increase the frequency or severity of seizures. About 50 % of patients respond favourably to valproate, ethosuximide or lamotrigine, either in monotherapy or in combination.2 However, treatment should be initiated carefully, since high doses of these drugs can also lead to an increase in seizure frequency, probably through the alteration of vigilance.

Figure 21.1: Ictal EEG during a myoclonic absence seizure.

In this patient, treatment was initiated with ethosuximide 250 mg twice daily using 62.5 mg/ml syrup; however, the syrup was changed to tablets after poor drug compliance and the dose was increased to 750 mg/day. At this dose the patient was reported to be slow and tired, and seizure frequency increased. After the dose was lowered to 500 mg/day, his seizure frequency decreased. Because we considered the ADHD symptoms to be secondary, no pharmacological treatment for ADHD was started. To assist the patient’s parents, practical counselling was provided in the home, especially focused on improving the family’s strategies for coping with the epilepsy and the bad behaviour and on implementing strategies to improve drug compliance. A behaviour modification programme was also started to reduce self-induction. About 1 years after starting this combined treatment strategy, the patient was considered almost seizure free.

Commentary

Why did we choose this case?

Although it is documented that the syndrome of myoclonic absence epilepsy is associated with mental retardation (in 45 % of patients at onset of the epilepsy, with a further 25 % developing mental retardation during the course of the disease),3 our case illustrates that the myoclonic jerks can also interfere with cognitive function and thus cause state-dependent cognitive impairment in addition to the trait-dependent impairments caused by the syndrome. Although photosensitivity is described as a rare comorbid symptom, seizures may be precipitated by light stimulation. In this case, self-induction was also present. This may contribute to the intractability in some cases and therefore compliance should be carefully monitored. Family counselling may be needed as in this case.

The differential diagnosis of myoclonic absence epilepsy may be difficult. For example, when there is a myoclonic component, the differential diagnosis may involve childhood or juvenile absence epilepsies; these, however, rarely affect the upper limbs (unlike myoclonic absence epilepsy). Moreover, in myoclonic absence seizures almost no eyelid twitching is present, unlike classical absences. EEG recordings may also be misinterpreted as classical 3-Hz spike–waves of classical absence epilepsy. In myoclonic absences the discharges are more irregular, there are more polyspikes and often there is an asymmetry. When myoclonic absences are suspected, an electromyogram of the shoulder muscles can be helpful in the differential diagnosis since the myoclonias may be very subtle, especially when patients are already being treated with anti-epileptic drugs. Every patient with absences that prove to be therapy resistant has to be regarded as suffering from myoclonic absences. The syndrome of myoclonic–astatic epilepsy has a similar age of onset and also combines absences with myoclonic seizures. There are, however, tonic–clonic seizures in the period before the onset of the absences and drop-attacks, and massive myoclonus that develops soon after the appearance of the absences. The myoclonic jerks in juvenile myoclonus epilepsy are briefer, and not associated with loss of consciousness, but are associated with tonic–clonic seizures without absences, and they start at a later age.

What did we learn from this case?

Apart from the above comments, we were particularly surprised by the significant impact...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- CONTRIBUTORS

- PREFACE

- I DIAGNOSTIC PUZZLES

- II INTRIGUING CAUSES AND CIRCUMSTANCES

- III SURPRISING TURNS AND TWISTS

- IV UNFORESEEN COMPLICATIONS AND PROBLEMS

- V UNEXPECTED SOLUTIONS

- VI CONCLUSION

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access One Hundred Case Studies in Epilepsy by Dieter Schmidt, Steven C. Schachter, Dieter Schmidt,Steven C. Schachter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Neurology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.