This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

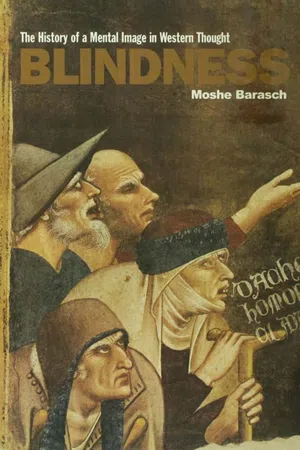

This is a remarkable study of how Western culture has represented blindness, especially in that most visual of arts, painting. Moshe Barasch draws upon not only the span of art history from antiquity to the eighteenth century but also the classical and biblical traditions that underpin so much of artistic representation: Blind Homer, the healing of

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Blindness by Moshe Barasch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Antiquity

Few periods in history, if indeed any, have been so fascinated with various figures of the blind, and have so deeply and vividly experienced the complexity and intricacy of blindness, as antiquity. The testimonies that have come down to us from the ancient world—texts and images, records of performances, rituals, stories—clearly suggest that blindness struck people both as a disaster and as an uncanny condition shrouded in mystery. Many explanations, sometimes contradictory, were offered to account for a mythological figure's loss of sight. Though living blind people hesitatingly groping their way must have been a common sight in everyday life in Greece and Rome, the explanations recorded in classical literature seem only to have deepened the sense of mystery that surrounded the sightless.

Blindness, needless to say, is a universal condition, and so also seems to be the reticence of society before the blind. So far as our knowledge and imagination can reach back into past ages, we find that there was probably no time and no society in which the blind were not tinged with some mystery. In many cultures, which need not detain us here, they were believed to have some contact with other worlds, with a reality different from the one in which we regularly live and altogether beyond the reach of other human beings. What precisely these “other” worlds’ realities actually were was not always clear, and views concerning their nature changed in the course of history. Yet whatever these invisible realities were believed to be, they determined how the blind were perceived and had an important effect on the understanding and classification of blindness. It is therefore necessary for the student to ask what were the particular contexts in which a given culture approached the blind.

In most societies and religious groups the approach to the blind and the interpretation of blindness reflect a coalescence, and even complete fusion, of attitudes that originally may have been distinct from each other. However, in the high cultures of antiquity these different attitudes in the experience and explanation of blindness remained more or less separated, each retaining its specific character.

In antiquity's experience and explanations of blindness, three different levels can be discerned tentatively. Levels of experience, as the student of cultural history need not be told, are never neatly separated from each other. Any attempt to make out watertight “levels” in a multifaceted, involved, and dynamic phenomenon will not enable us to grasp the amplitude and interaction of multilayered social and cultural phenomena; in the end, it will inevitably turn out to be an arbitrary construction. Yet the historian cannot abstain from trying to distinguish some structure, even in a phenomenon as fluent, and sometimes contorted, as antiquity's attitude to blindness. The attempt to uncover an underlying, hidden structure helps us to see more clearly what, in fact, were the major components and aspects of that period's view of the blind. Three levels of experience and explanation should be considered here.

On the level of direct, immediate experience, blindness is naturally perceived as a grave physical injury, the impairment of one of the body's essential functions. As such it is the subject matter of emotional and social attitudes, and to some extent, though a surprisingly small one, also of medical science. It is of interest for us to note that on the level of immediate experience in antiquity the external appearance of a blind person was carefully observed and recorded. The posture of his head and body, his hesitating movements, the stick he holds in his hand, or the people who guide and help him—all this was noted and described in detail. These features became marks identifying a figure as blind, even if one could not see the face. Such observations were cast into visual formulae and became configurations that were to persist for long periods. Expressions of emotional reactions, of pity and compassion for the blind one's unfortunate condition, are often encountered. They permeated the visual outlines of the blind person's image in antiquity, and thus determined how he was represented in art and retained in cultural memory.

A second level of antiquity's approach to blindness is the concern for the causes that bring about the condition. Here one does not ask, How do the blind look? but, Why are they blind? The direct, immediate experience of blindness, even in the forms we know from antiquity, is not specific only to this period. The appearance of the blind is intuitively grasped in all ages. The quest for the reasons of blindness, however, and the explanations offered in the ancient world, are specific to antiquity. At the least, they make the distance between the ancient and the modern approach instantly manifest. In ancient culture, natural causes are sometimes suggested to explain blindness, but most explanations go beyond this realm. It is supernatural forces, gods or demons, and their intervention in human affairs, that strike some people blind. The intervention of gods or demons in blinding a person is usually understood as a punishment for the transgression of a basic natural, moral, or religious law. In some way, then, the blind one is a delinquent, and his blindness always reminds us of his grave guilt.

A third, and final, level is the belief, common in classical culture, that blindness as such has some inherent meaning of its own. Though the meaning of blindness could perhaps not be totally separated from what the blind person has done in the past, or from the guilt he inherited, the meaning of blindness was not fully identical with the events that caused it. In most ancient cultures one could therefore ask: What does blindness mean? The quest for this meaning is the third level on which antiquity attempted to unriddle what appeared to the period as the mystery of blindness. To be sure, the “meaning” of this condition was never clearly defined; on this level, vagueness and ambiguity are more prevalent than on the others. But the belief that blindness as such, whatever its causes in a particular case, has a meaning was strong enough to persist for centuries. It was a belief that had a lasting influence on reflections and imagery associated with the blind.

One of the important, though not intentionally sought, effects of the beliefs in the inherent meaning of blindness was the blurring of the division between physical and metaphorical blindness. Already in Greek culture the obfuscation of the division between the physical and the metaphorical senses of blindness became a great theme and had a powerful afterlife in European imagery. We begin our discussion with a glance at what was thought about the causes and meaning of blindness, and only later shall we return to the external appearance of the blind.

As in so many fields, the legacy of antiquity, both that of the biblical and of the Greco-Roman world, was a significant factor in shaping the mental attitude toward the blind in later stages of Western thought and imagery. In briefly discussing some testimonies of the ancient world, we should, therefore, ask not only how in ancient times people actually approached the blind on the street but also, perhaps first of all, what was the mental image of the sightless that antiquity bequeathed to later ages.

The essential characteristic of the blind person's figure, as it appeared to the ancient mind, is his ambiguity. He is not perceived as either good or bad, trustworthy or suspicious, unfortunate or blessed; he is all that at the same time. On the one hand, he is the unfortunate person deprived of sight, the most valuable of senses; on the other, he is often endowed with a mysterious, supernatural ability. This ambiguity of the blind person's nature may explain how it was possible for audiences to have pity and compassion for him, but at the same time also to sense awe and perhaps anxiety in meeting him. Later periods, as we shall see, stressed more the one or the other side, but the blind man's double face had a long lease on life.

Ambiguity itself is elusive, and it does not capture the image of the blind with sufficient distinctiveness. In the Bible the blind evoke compassion, but because of their “blemish” they cannot participate in rituals. In Greco-Roman antiquity attempts were made to give them a more distinct character. A brief discussion, in the course of this chapter, of some ancient texts and some pieces of ancient art will show that the two sides of the figure, the guilt as well as the prophetic gift, are of sublime origin. As far as we can see from ancient literature, the blind person's guilt is not a humiliating one. He is not imagined as a liar or a thief or as committing a mean crime. His culpability is mainly the fault of having seen the gods when mortals are not supposed to see them. In other words, it is an offense to the gods, even if without sacrilegious intention. Such transgression implies that the guilty one had some contact with the divine, whatever the nature of that contact might be. The guilt may be inherited, thus suggesting that the blind person's forefathers already had some contact with the gods. Other maimed people were sometimes also believed to be guilty of a crime, but only the guilt of the blind is derived from an encounter with the divine. This unique, elevated origin of his guilt sets the blind man apart from all other people punished by suffering a physical deprivation. Later ages, as we shall see in the following chapters, took over the belief that the blind are burdened with some kind of culpability. The noble nature and elevated origin of that guilt were forgotten. The stories of the blind once having met, or at least seen, a god or a goddess were no longer recalled by periods for which gods or goddesses were devoid of any reality. What remained was the belief that the blind are persons that are not trustworthy and are to be treated with suspicion.

Further significant testimony to the blind person's particular status was the belief, widespread in the ancient world, that he had been granted the ability to communicate with worlds that are outside the reach of mortal human beings. Nothing has made the blind into such a mysterious, uncanny figure in the cultural imagery of Europe as the belief that he can reach where others cannot. As we shall see in the present chapter, Greek antiquity itself tried to account for this unusual gift of the sightless, or at least of some of them. The power to reach into worlds beyond our regular experience was explained as a gift, a particular favor granted by the gods. Since it is a divine gift, it is in itself mysterious and without explanation. One notes that, as the guilt of the blind often originates in the contact with the gods, so the unique ability of some of them is also directly given by the gods. The blind's proximity to the gods, whether intentional or fortuitous, hidden or explicit, remains part of their fate.

Tracing the intrinsic boundaries of this mysterious ability sheds light on its nature. Other periods and cultures have also singled out some individuals and believed that they could have contact with the divine. The use to which this power is put, however, varies. From Christian lore, for example, we are familiar with the belief that the saints (some of whom have such mysterious power) can intercede for believers. This is altogether different in antiquity. Here the blind do not even attempt to intercede. The gift they have received from the gods is not the power of intercession; it is the power to see what will happen, that is, to know the future. It is a sublimated, spiritualized form of vision. What the blind person has lost in his body, the sight of his eyes, he is, at least in some cases, given back in spirit.

We now turn to an analysis of some individual aspects of this image of the blind.

Attitudes of the Bible

For an understanding of the mental image that European culture formed of the blind, and particularly the moral and religious connotations that blindness carried from the early Middle Ages to the beginning of the modern period, we have to begin with the Bible. Whether or not the Bible fully reflects the views of the blind that were current in ancient Near Eastern societies and cultures is not our concern here.1 In the minds of European writers and artists between the disintegration of the ancient world and the baroque period the Bible was the beginning of explicit attitudes toward blindness, and it was invested with supreme religious authority.

The biblical corpus deals with the blind in two different thematic spheres, and they are clearly separated into two classes of texts. The aspect from which the blind are approached in one class is slightly different from that of the other. For our present purpose, one sphere may be termed “narrative,” the other “prescriptive.” The former pertains to the domain of stories, whether mythical, symbolic, or historical. The latter belongs to the realm of ritual custom and religious law. In the first group of texts, the views about blindness are implicit; they are conveyed by the context of the story and the general character of the figure. A good example is the blindness of old Isaac, who has to touch his sons to distinguish between them. Though even here the ideas about the blind and blindness sometimes emerge rather clearly from the events narrated, they are not stated directly. This is altogether different in the prescriptive texts. In the sphere of ritual and legal prescriptions views about blindness are stated directly and explicitly. Though here, as a rule, little is said about the individual blind person, about his character, motives, or fate, his status in society is sharply defined, and it is made abundantly clear what he may, or may not, do and what functions he may, or may not, fulfill. It is natural, therefore, that the evaluation of the blind personage emerging from the stories narrated is sometimes vague in meaning; in some cases it may even be thoroughly ambiguous. On the other hand, the attitude recorded in the prescriptions is explicit, and as a general rule it does not allow for differing interpretations.

The nature and context of blindness that emerge from the narrative texts of the Bible are not uniform. Blindness neither has a single cause, nor does it necessarily bear testimony to a single reason (though often it does). In its most dramatic form, it is one of the most severe punishments that can be thought of. As such it is highlighted in the act of blinding. None of the biblical stories of blinding indicate anything mysterious. It is worth noting that most of those blinded are not punished by God, but by their enemies. The blinding of Samson, the best-known story of this type, is not the only one. In some stories, blinding is presented as reflecting a widely accepted norm of political and social procedure in certain exceptional conditions. Thus Zedekiah, the king of Jerusalem who rebelled against the ruler of Babylon, is defeated by the great military power of the Babylonians and cruelly punished. After defeating the rebellious leader, “they [the Babylonians] took the king [Zedekiah] and brought him up to the king of Babylon to Riblah; and they gave judgment upon him. And they slew the sons of Zedekiah before his eyes, and put out the eyes of Zedekiah, and bound him with fetters and brass, and carried him to Babylon.”2

Though it is said that Zedekiah “did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord” (2 Kings 24:19), the text does not suggest that his blinding is understood as a punishment by God. It is the conduct of a mighty ruler, the king of Babylon, who thus punishes the defeated commander who dared to rebel against him.

As a component of manifesting victory, the total or partial blinding of the defeated enemy also explicitly carries the connotation of the lowest, most offensive degradation that could be inflicted upon man. ...

Table of contents

- Frontcover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Antiquity

- 2 The Blind in the Early Christian World

- 3 The Middle Ages

- 4 The Renaissance and Its Sequel

- 5 The Disenchantment of Blindness: Diderot’s Lettre sur les aveugles

- Notes

- Index