This is a test

- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Music of Louis Andriessen

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book presents the musician in dialog with a Polish-Canadian musicologist and three of his Dutch friends and collaborators, Reinbert de Leeuw, Elmer Schönberger and Frits van der Waa. Topics include his artistic evolution, his relationship to minimalism, his prevalent interest in mysticism and meaning, the use of quotation and writing for

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Music of Louis Andriessen by Maja Trochimczyk, Maja Trochimczyk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Composing

3

The Man and His Music: A Portrait

Maja Trochimczyk

1. A Life in Three Snapshots

Snapshot 1: 1940s

A boy, six or seven years old, wearing a casual shirt and shorts, sits on the edge of a bench in a city garden and intently watches his father who sits next to him with a long stick in his hands (see Figure 3.1)1 The father is formally dressed in a suit and tie and seems focused on the stick, exuding the self-assured aura of a professional— a college director, or a church musician, perhaps. The mother looks on from the other side, with her hair neatly parted and her face framed by a lovely white lace

Figure 3.1 Andriessen and parents, ca. 1940.

collar with a brooch. Her conservative dark dress, like the father's suit, is too formal for the occasion, an afternoon in the garden with their youngest son. What are they doing? Up closer examination we may notice the thin shadow of a string: the Dad is making a bow for his little son who patiently waits for the new toy.

This time alone with his parents must have been a treat for Louis, the youngest of six children (born on 6 June 1939 in Utrecht). His parents, Henrik Andriessen (1892–1981) and Johanna (Tine) Anschütz (1898–1975) also had to devote their attention to his older siblings: Gesina, Helena, Nico, Jurriaan, and Caecilia.2 Yet his childhood, if judged from this image, was a happy and affluent one: the photo documents a moment in the life of people who could afford to buy better toys,3 yet chose to spend quality time with their beloved child instead— making something that would be, most likely, soon broken and discarded. Yet there is a hint of austere devotion to duty and discipline in the formality of their apparel and their poise. The boy, as any boy that age, has little self-awareness: he seems totally engrossed in the actions of his father.

Snapshot 2: 1970s

This admiration later brought musical results: the boy grew up to be a composer. He studied at home with his father, at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague with Kees van Baaren, and with Luciano Berio in Milan and Berlin. His early works

Figure 3.2 Andriessen (1975).

reflected a fascination with modernism (the use of serial techniques in Series for two pianos; the presence of quotations in Anachronie I and Anachronie II, etc.). In mid-1960s Andriessen moved to Amsterdam and became an active member of the radical avant-garde. Among their most notorious actions was the disrupting of the inaugural concert of the Concertgebouw Orchestra under Bernard Haitink in 1972. The musical revolutionaries demanded that the Orchestra disband to create a collective of musicians, directed by the progressive conductor and modernist composer Bruno Maderna. When their demand was not heard, Andriessen and his free-thinking colleagues founded just this kind of artistic collective, De Volharding, consisting of jazz and classically-trained musicians. De Volharding performed during demonstrations and rallies, in city parks and clubs; its repertoire freely mixed elements of jazz and musical modernism. Andriessen served as the ensemble’s pianist; this experience resulted in a change of his musical language.

In a portrait reproduced as Figure 3.2, the composer (with fashionably long and disheveled hair) seems lost in thought, contemplating an unnamed score, perhaps a recent composition. Could it be De Staat for female voices and instrumental ensemble? The 1976 work was his ticket to international recognition: the first prize at the UNESCO International Rostrum of Composers in 1977 resulted in broadcasts of De Staat by all participating radio stations, from virtually everywhere around the world. The Dutch Matthijs Vermeulen Prize of the same year sealed Louis Andriessen's position as the leader of his generation in Holland.

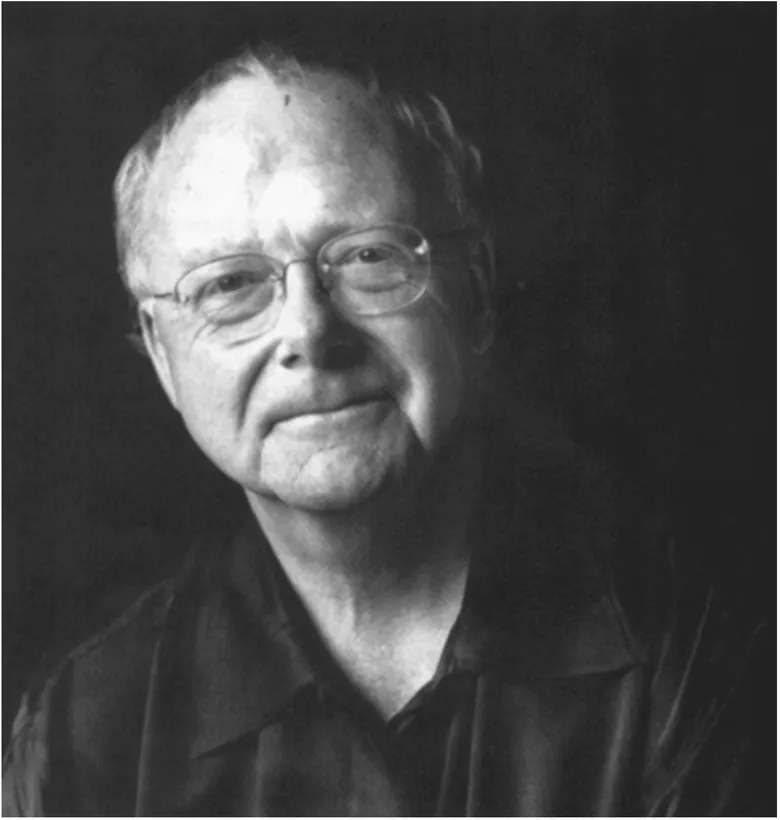

Snapshot No. 3: 1990s

Finally, we see his eyes: the most striking feature of his mature and half-smiling round face with a broad forehead. Andriessen looks through metal-rimmed glasses with the knowing air of someone who has already faced death and lived to tell about it (see Figure 3.3) His eyes, surrounded by the wrinkles of someone who smiles too much, shine with intelligence and goodness. The composer has reached the apex of strength, compassion, and self-awareness. No wonder young composers flock to study with him: Steve Martland from Britain, Ron Ford from the U.S., Hanna Kulenty from Poland, and fellow-Dutchman Martijn Padding, who is Andriessen's favorite student (now entrusted with the artistic leadership of De Volharding). If the composer's whole figure appeared in the photo we would notice that the "hippie" clothing with florid designs has been replaced by one of his trademark silk shirts; he still doesn't wear a tie. This is a composer of international stature, someone successful and happy with his life of musical achievement: from the monumentally reductive and seductive De Tijd (1981), through operas De Materie (1985–88; a collaboration with Robert Wilson) and Rosa: A Horse Drama (1993–94; a collaboration with Peter Greenaway), to the grimly striking The Trilogy of the Last Day (1995–96). Commissions, awards, recording contracts, lecture invitations abound; Andriessen is now a veritable institution in Dutch musical life, and he knows it, too.

Figure 3.3 Andriessen (1999). Photo by Rosa Verhoeve.

2. The Oeuvre

Louis Andriessen's files in the Donemus Archives in Amsterdam contain surprising findings among the thousands of press clippings from the past forty years; here you may find the text of a congratulatory poem from Andriessen's wedding to Jeannette Yanikian or a diagram of his major works between De Staat (1976) and Hout (1991). The diagram (see Figure 3.4 below), set as a series of vertical blocks on a horizontal line, includes the titles of what at this point were the most important compositions in his oeuvre. The first composition on the diagram made him an internationally-known, rather than only Dutch, composer: De Staat (1976) to texts from Plato's Politeia is a voice in the perennial discussion about the relationship between music and the state. Andriessen’s program note for this piece contains his artistic/political credo from the 1970s:

Many composers feel that the act of composing is "suprasocial." I don't agree. How you arrange your musical material, what you do with it, the techniques you use, the instruments you score for, all of this is determined to a large extent by your own social circumstances, your education, environment and listening experience, and the availability—or non-availability—of symphony orchestra and government grants. The only point on which I agree with the liberal idealists is that abstract musical material—pitch, duration, rhythm—is suprasocial. It is part of nature. There is no such thing as a fascist dominant seventh.4

The composer adds a regret that perhaps "Plato was wrong: if only it were true that musical innovation represented a danger to the State!" Then, you could cause a social revolution by making music—an enticing proposition for a revolutionary with a big, anarchist agenda. Yet De Staat proved to be as revolutionary as its composer's wishes; the work's triumphant march through the concert stages of Europe and North America brought praise from all quarters: Robert Cowan described it as "both stimulating and healthily unsettling" while Elmer Schönberger wrote that in this work, "Andriessen has tried his strength against minimal music and has succeeded in subordinating those techniques to new expressive objectives."5 K. Robert Schwarz, the author of a monograph on the minimalists, first described the sonic world of De Staat as consisting of a "fierce, deafening and relentless sonic assault of woodwind, brass and percussion," then stated that "no one else has so convincingly united the best of European modernism with the best of American Minimalism. Somehow, Mr. Andriessen preserves Stravinsky's abrasive edge and rigid backbone without negating a Reichian accessibility."6

Compared with what could be heard in the European concert halls of the time, the sound world of De Staat is indeed strikingly original, starting from the tetrachordal meanderings of the woodwinds that open the work—a relentless passage in irregular meter, based on the rhythmic unit of the eighth note (Example 3.1: The beginning of De Staat).

Four female voices are amplified and sing non-vibrato; this is an import from beyond the classical music domain, most likely from jazz, though the tight, dissonant harmonies bring to mind Stravinsky's stylizations of Russian folklore in Stravinsky's Svadebka [Les Noces]. In accordance with the fashion of "spatial

Example 3.1 The beginning of De Staat (1976) © Copyright 1994 by Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

ized music" popular at the time, the instruments are dispersed on the stage in a layout printed in the score: two groups echo each other's material with identical settings, including abundant brass, pianos, harps, percussion, and electric guitars. The center of the stage is taken by the "Buddha" of all instruments in De Staat, the voice of the Gods, as it were—the bass guitar. In his program note, Andriessen claims that its uniqueness has a musical justification. "There may be only one bass line in a composition." At the end of De Staat, the bass guitar finally teaches the other instruments what their unified melody should be and the unison slowly emerges from an awkwardly misguided canon.7

The nearest two large blocks on the composer's diagram of his oeuvre represent Mausoleum (1979) and De Tijd (1981), both scored for amplified voices and large, unconventional ensembles. Interestingly, the three compositions mentioned here (De Staat, Mausoleum, and De Tijd) were sometimes considered a trilogy, for instance by Keith Potter in 1981. The commonality of vocal-instrumental settings may have been a factor in this designation, since these pieces seem to have little in common in terms of political content and aesthetic form. In 1978, Elmer Schönberger arranged Andriessen's works into another trilogy, one consisting of De Staat, Il Principe (for two choirs and instrumental ensemble, 1974) and Il Duce (electronic piece of 1973).8 These three political compositions—almost manifestos—aim to contest and criticize society through sound: "Radical here means one-dimensional. Continuous fortissimo, in principle unison, extremely restricted material, but with the effect of one dimension which gives the impression of ten."9 Interestingly, neither of the two works that preceded De Staat as a preliminary stage in the working out of ideas made it into Andriessen's sketch in 1991 of the music that mattered to him. In contrast, Mausoleum (to anarchist texts by Mikhail Bakunin) and De Tijd [Time] (to an excerpt from St. Augustine's Confessions dealing with the philosophy of time and timelessness) remained among his monumental achievements.

Of less importance was the widely played, controversial (for being too limited in material and form) Hoketus (1977), for two identical ensembles engaged in a fierce musical competition, trying to unsettle each other's regularity of repetitions. This work is marked with a smaller, thin line. It may be seen as a sonic elucidation of reasons for the violent rejection of minimalism by musically sophisticated readers. If development of form is what you expect from a successful composition, you are bound to be disappointed, since Hoketus will give you an extended sequence of alternating loud and dissonant chords played by competing groups of musicians.10

De Snelheid [Velocity] (1982–83) is the last significant work before a large gap on Andriessen's diagram. This composition c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- General Introduction to Studies in Contemporary Music and Culture

- Preface

- I Learning

- II Composing

- III Ideas

- IV Art

- Chronological List of Works by Louis Andriessen

- Select Bibliography

- Discography

- Index