eBook - ePub

Medical Microbiology Testing in Primary Care

This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Medical Microbiology Testing in Primary Care

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The book's purpose is to help community-based primary care physicians and nurses, and laboratory-based microbiologists, better understand each other's requirements in collecting and interpreting specimens, and thus to improve the quality of patient care, while saving resources and reducing unnecessary antibiotic prescription.The book's structure fo

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Medical Microbiology Testing in Primary Care by J. Keith Struthers, Michael Weinbren, Christopher Taggart, Kjell Wiberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medizin & Medizinische Theorie, Praxis & Referenz. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Introduction

• Introduction

• Critical steps

• Assessing one’s own microbiology knowledge

• The laboratory repertoire

• Specimen collection

• The request form

• The role of the laboratory

• Epidemiology of specimens received from primary care

• Public health and the community

• Notification of infectious diseases and causative agents

• Summary and key points

INTRODUCTION

The complexity of medicine has changed significantly in recent years. This makes it difficult for those, both in training and in practice, to maintain the breadth of knowledge sufficient always to deal effectively with patients presenting with conditions spanning all the disciplines. Medical microbiology is no exception. While most doctors in the developed world have unrestricted access to the laboratory and the diverse range of tests available, knowing how to use these facilities and interpret laboratory results is a prerequisite for ensuring good quality, safe and cost-effective patient care.

Incorrect use of the laboratory and misinterpretation of a report wastes money and can compromise patient care, but how often does this actually occur? Is this occasionally, weekly, or daily? Practising microbiologists would state that this situation arises frequently both in primary care and the hospital setting across the strata of grades of experience. As evidence, when 130 primary care physicians were asked to interpret reports based on situations they would regularly encounter, their responses resulted in incorrect management in over 50% of cases. The purpose of this book is not to teach medical microbiology. It is to provide an understanding of the essential principles which are applicable at key steps in the process, from considering whether to take a specimen through to interpreting the result.

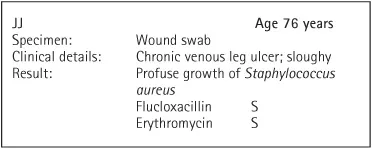

A report of a wound swab is shown below:

The swab may have been requested by yourself, but not uncommonly it may have been collected by a practice/clinic partner or nurse, or taken in hospital. You are now being asked by the nurse to prescribe antibiotics; what do you do? One’s natural instinct may be to prescribe flucloxacillin or erythromycin; however, is this the correct action to take? Frequently this is not the case. The key to interpreting any report is knowledge and implementation of a few essential principles. Too often a laboratory report listing an organism and its antibiotic susceptibility profile is seen as a directive to start treatment. Why would this be incorrect? Although Staphylococcus aureus is the major cause of wound/soft tissue infections, it can ‘colonize’ an ulcer or wound (i.e. it is present on the surface of the wound but not causing any harm). In such a situation antibiotic therapy is not warranted. However, if there is evidence of infection, for example cellulitis around the ulcer, an antibiotic would be indicated.

When reviewing a laboratory report, the reason for the specimen being collected should be checked; was it taken because there was clinical evidence of infection? If there was and a recognized pathogen identified, then the treatment decision would be straightforward. Frequently however, leg ulcers are swabbed as a matter of ‘routine’ irrespective of whether there is infection or not. Once taken, a chain of events is initiated that not only wastes resources, but which can ultimately result in patient harm. The points below highlight key consequences of inappropriate specimen collection:

• The financial cost of the unnecessary specimen.

• The financial cost of inappropriate antibiotic prescription.

• The side-effects associated with antibiotic use.

• The selection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

• The risk of the patient acquiring Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea (CDAD). The risk of this potentially life-threatening infection must always be considered.

• The risk of ‘medicalizing’ the condition, with patient expectation that an antibiotic should be given.

CRITICAL STEPS

Central to this book is the identification of seven critical steps from deciding why to take the specimen through to interpreting the laboratory report. A scenario is given at the beginning of Chapters 3–10. The purpose of these is to highlight steps which have a major bearing (critical control point) on the outcome of a consultation, should a laboratory test be ordered.

While several of the critical steps (4–6) are the responsibility of transport logistics and the laboratory, steps 1, 2, 3, and 7 have been identified to facilitate improvement in patient care, which can be used by health-care workers (HCW) as an audit and educational tool within the primary care setting.

For example, critical step 1 centres on criteria that should be used when considering collecting a specimen. In the example given in 1, page 11, what should prompt taking a swab from a leg ulcer? This can lead to an interesting discussion, as the reasons for swabbing may be highly varied, and the process should be educational. The endpoint should be to agree a protocol for when to take a swab. Unless screening for an organism such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), the specimen should be collected only when there is clinical evidence of infection. By using steps 1, 2, 3, and 7 it should be possible to reduce the number of unnecessary specimens collected and the inappropriate treatment of patients, which will result in financial savings.

ASSESSING ONE’S OWN MICROBIOLOGY KNOWLEDGE

With reference to the survey of 130 primary care physicians cited above, they were presented with 12 common laboratory reports and were asked how they would manage each situation. Over 50% of the responses would have resulted in incorrect management. These scenarios plus eight others are presented in the appendix of this chapter as questions and answers, and we recommend that you do this exercise, which sets the theme for the book. As a minimum, appreciating and applying the basic principles arising from these 20 scenarios, which are encountered frequently, would improve medical practice. Even if the individual scores well, it is likely that other staff members would benefit from the quiz.

THE LABORATORY REPERTOIRE

Primary care submits a wide range of specimen types to the medical microbiology laboratory (2, page 12).1, 2 For bacteriology, culture on agar plates is the main method used to isolate, identify bacteria, and determine their antibiotic susceptibility profile. Mycology includes microscopy and culture for dermatophytes in skin scrapings, nail clippings, and scalp hairs. Virology is the domain of the wide range of serological tests for antigens of, and antibodies to, most medically important viruses. In addition, antibody tests for bacteria such as treponema and leptospira are conducted in the virology section. Growing viruses in tissue culture for identification has largely been superseded by nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR tests are available for chlamydia and most viruses including herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), and mumps. In addition, it is available for a range of respiratory pathogens including mycoplasma, influenza, and respiratory syncitial virus (RSV). PCR is integral in the management of antiviral regimes used in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV).

The 2009 H1N1 swine flu pandemic identified the challenges, in the UK at least, of introducing a new PCR-based diagnostic test for use in both the community and hospital setting. The availability of PCR tests in microbiology and virology should be confirmed with the local laboratory.

SPECIMEN COLLECTION

Highlighted in the first figure of each of Chapters 3–10 are key points in the collection and storage of the various types of specimen. These points are emphasized in more detail in each chapter, and the accompanying Quick Action Guide. Critical step 2 also covers this in detail. Staff needs to know how to collect a good quality specimen. Where patients are expected to collect their own specimen, they need to be given appropriate advice on how to do so. Failure to give this advice can invalidate the whole process. One example is the female patient not being given practical advice on how to collect a urine specimen at home (see Chapter 3, 45, 46).

THE REQUEST FORM

To ensure that the correct tests are done, the request form accompanying the specimen should include comments on the clinical situation, relevant travel and occupational details, antibiotic allergies, as well as current and proposed antibiotic use. Further tests may be done on the basis of this information. The laboratory is responsible for providing useful information on the report that can be used directly to manage the patient. Examples of the details that should be recorded on request forms and laboratory reports are shown in 3, page 13. ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Medical Microbiology Testing

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- DISCLAIMER

- PREFACE

- ABBREVIATIONS

- 1 The Introduction

- 2 Organisms and Antibiotics

- 3 The Urine Specimen

- 4 The Genital Specimen

- 5 The Swab of the Chronic Leg Ulcer

- 6 Fungal Scrapings of the Nail Apparatus (Onychomycosis), the Hair, and the Skin

- 7 The Faecal Specimen

- 8 The Eye and the Respiratory Tract Specimen

- 9 The Serology Specimen

- 10 Infections in Pregnancy

- 11 Antibiotic Guidelines

- Self-Assessment Review Cases

- Appendix

- References

- Index