- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Redefining Brutalism

About this book

There is a genuine resurgence of interest in this period of architecture. Brutalism is a highly debated topic in the architectural press and amongst architectural critics and institutions who promote the preservation of these buildings. This book is unique in combining beautiful, highly illustrated design with description of both British and International brutalist buildings and architects, alongside analysis of the present and future of brutalism. Not just be a historical tome, this book discusses brutalism as a living and evolving entity.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralOne

Brutalism is not a Corpse

Rough, grey concrete. It is the stuff from which our postwar cities were made. Concrete piled up on concrete. In our imaginations, Brutalism is synonymous with this material. Monolithic, heavy and inscrutable, unfamiliar and incomprehensibly unfriendly, it seemed at a certain point in history to invade our cities. Particularly in Europe, there is a sense that this new architecture filled the void left by the destruction of the Second World War. It did. Although not quite as quickly and inevitably as it would appear. These alien structures brought with them a different kind of city. Not one of streets and squares but of freestanding sculptural buildings set in bleak, open spaces. A new order had been overlaid on the city and it didn’t make much sense. Then, it might have been exciting. Today, it seems cold. These perceptions precipitated its downfall.

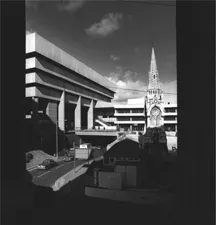

Figure 1.1: Birmingham Central Library, John Madin Design Group, 1964‑1974

Figure 1.2: Aviary, London Zoo – a Brutalist precursor to High-tech, Cedric Price, 1961–2

Figure 1.3: Fire Station No. 4, Columbus, Indiana, Venturi and Rauch, 1966–8

Brutalism was destroyed by two schools of thought. The first envisaged that the continuation of the ‘Modern Project’ should, as Archigram’s illustrations and Cedric Price’s aphorisms suggested, be populist, light, efficient and fun. Their ideas – along with those of Jean Prouvé, Richard Buckminster Fuller and Louis Kahn – spawned the High-tech. The other school of thought, Postmodernism – at least, the strand of thinking that employed familiar architectural elements drawn mainly from Classical architecture – rejected abstraction and sought, through semiotics, to communicate figuratively.

So why, in the space of a short paragraph, do I appear to condemn the very subject of this book and, in a second paragraph, skip to the schools of thought that killed it off? Because what I describe is a tragic oversimplification. It is the way we talk about Brutalism when we don’t understand it. It is the view of the sceptic, the ill-informed and the uninterested. It is, in fact, a far more complex subject than that. Brutalism doesn’t just equal concrete. It isn’t only found in windswept plazas. It’s not limited to Europe and North America. And, most importantly, I believe, it’s not something from the past, from those postwar years. It is very much alive. It is a reason for making buildings. Furthermore, it’s not bland. It is quite beautiful. The poetry

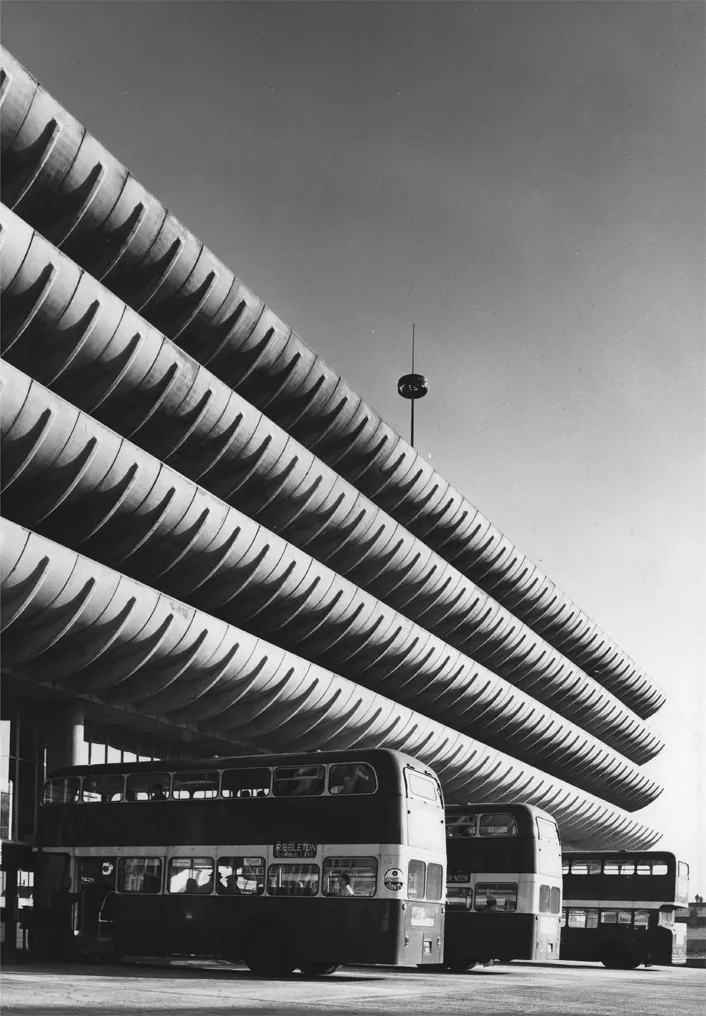

Figure 1.4: Preston Bus Station, Grenfell Baines & Hargreaves, 1968–9

is not hard to see. It is material. The architect’s search for a language swings between plainer forms of expressed construction and a way of building that explores their decorative potential. These two apparently contrary positions form a dialectic within which architects oscillate and their buildings may be read. It should not be surprising, therefore, that Brutalism could be a living tradition.

Figure 1.5: Eberswalde Technical School Library, Herzog & de Meuron, 1994–9

This book seeks to describe Brutalist architecture in its various guises and, in so doing, to speculate on a multitude of definitions. Was Brutalism inevitable? Was it just a poetic phenomenon? Was it expedient and economic? Was it philosophical and political? Was it, as critic Reyner Banham asked, an ‘Ethic or Aesthetic’? It was all of these things because the circumstances in which these buildings were designed and made varied, and the motivations of those involved differed. In the 1960s, in the UK, governments marshalled house builders to deliver hundreds of thousands of homes per year. This led to factories manufacturing precast concrete elements on an industrial scale. Very different from a South American architect seeking a language, and way of building, that might begin to represent an emerging nation on the world stage. And, neither can we explain why a convent or a theatre should, if indeed they did, have anything in common with one another.

Recent events have brought the phenomenon to our attention: Haworth Tompkins’ celebrated conservation work on Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre in the UK; the demolition of Bertrand Goldberg’s Prentice Hospital in Chicago in 2014; the staging in 2015 of the ‘Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955–1980’ exhibition by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, to mark the 60th anniversary of the seminal ‘Latin American Architecture since 1945’ exhibition; then, in 2016, after nearly 30 years of their being at risk of demolition or subordination, the renovation of the Hayward Gallery, Queen Elizabeth Hall and Purcell Room on London’s South Bank began;1 in the same year, Dublin-based Grafton Architects won the first RIBA International Prize for their concrete megastructure, UTEC Lima, in Peru; and the Brazilian architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha received the 2017 Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects.

This should not come as a surprise. For years, Herzog & de Meuron have been making raw buildings. Their early works were invariably simplified forms employing just one material: Stone House (1982–8), Plywood House (1984–5), the fibre-reinforced cement-board Ricola Storage Building (1986–7) and their concrete Antipodes 1 Student Housing for the University of Burgundy, Dijon (1990–2). Then, with their Eberswalde Technical School Library in Germany, they overturned in a single work the idea that Brutalism and decoration were contradictory and incompatible positions. Here was a building, quite simply a box, devoid of any formal detail, faced in concrete panels, with functionally distributed windows, relieved only by the presence of photographic images etched on the face of the panels. Eberswalde picked up where late postwar Brutalism left off, with its often ornate use of concrete moulds and finishing techniques. Many others – including the Swiss architect Peter Märkli, the Irish practice O’Donnell + Tuomey, the Chilean studio Pezo von Ellrichshausen Arquitectos and the Whisperers2 in the UK – have all recently concerned themselves with Brutalism.

However, two men who have practised continuously since the 1950s offer the strongest link between generations. The first, Paulo Mendes da Rocha, a member of the Paulist School, has worked consistently, often but not exclusively with in-situ concrete, with direct construction and emblematic engineering. From his earliest work this Marxist architect has sought to reinforce the public character of the metropolis. His gymnasium for the Clube Atlético Paulistano in São Paulo (1957–8) – a huge disc of concrete – doesn’t create enclosure in the city, instead shelters a small part of it. His Brazilian Museum of Sculpture MUBE (1986–95), also in São Paulo, using the fall of the land places the museum largely underground and makes instead, in collaboration with the landscape architect Robert Burle Marx, a model Brazilian garden of water, trees and indigenous plant species, the only substantial built form being a loggia – a beam of in situ concrete – some 60m long and 12m wide. His work is concrete, steel, and glass, consistently tough, often but not always rough, usually defying gravity, and concerned with the city as a public landscape which is both able to catalyse and give sanctuary to an urban population by means of civic structures.

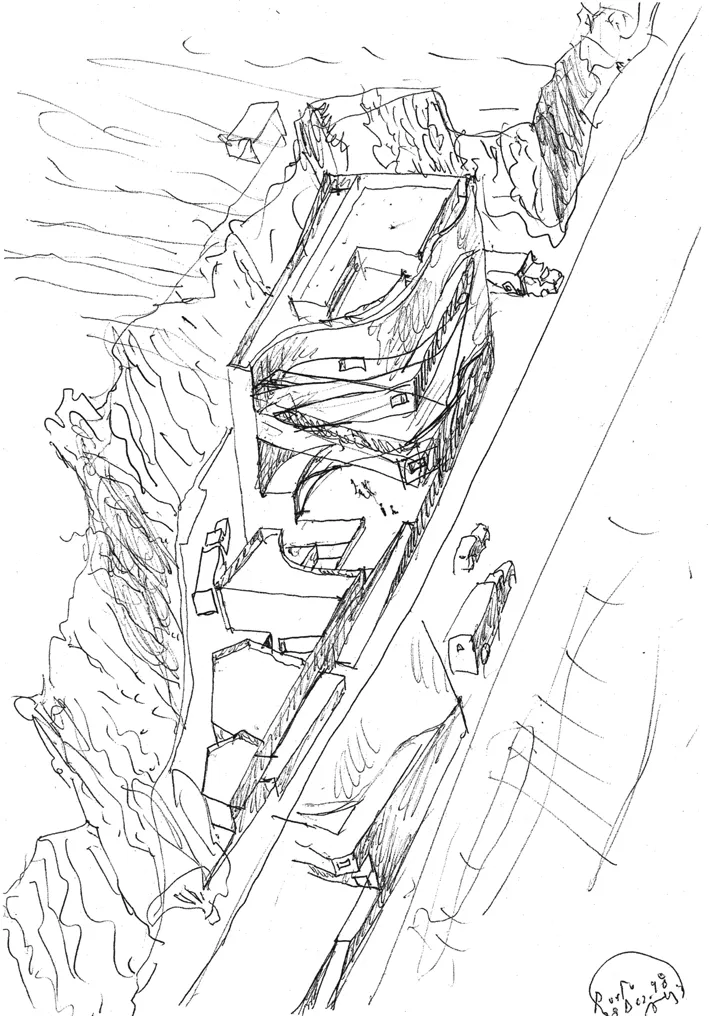

The second, the Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza, began practice in 1954. His Cooperativa do Lordelo (1960–3) and Piscina de Leça da Palmeira (1961–6) were both rough béton brut, ‘the wood formwork bestowing the facades a quasi-mineral surface’.3 But from about 1970, with the arrival of Postmodernism, Siza turned to the white, plastic, ground-bearing architecture for which he is mostly known. For 30 years, his palette was restricted to render, even if beneath was concrete. His unique combination of critical regionalism and early Corbusian Purism was implicitly resistant to the prevailing language of Postmodernism. Times change. Since the Millennium, he has been working in stone; brick; timber; and, most consistently, exposed concrete – and, in the case of the Museum for the Ibere Camargo Foundation in Brazil (1998–2008) and the Municipal Library in Viana do Castelo (1998–2008), a bloody-minded concern for structure and form that one would expect of Lina Bo Bardi. It becomes increasingly apparent in the work of such thoughtful architects that Brutalism is an enduring dimension of praxis.

After the Second World War, concrete was in vogue. To build in concrete was quite simply avant-garde. Yet, it was more than a style; it was, and remains, a sensibility. It is a way of thinking and a way of making. It affects the way things look and the way they feel. It is

Figure 1.6: Plan of the swimming pool in Leça da Palmeira, Álvaro Siza, 1961–6

vivid – ‘rough’ and ‘tough’.4 We associate it with the postwar city, with cities that were badly bombed. Much of the reconstruction was in monolithic concrete: vessels elevated on pilotis, or bunker-like with few windows – not inclined to engage with the city as it was, their use not always evident to the passerby. Hard to read. Difficult to comprehend. But Brutalism is eclectic. It is not limited to cities, or concrete. It may be minimal in its detail; it may even seem to have been decorated.

Much that has been written about Brutalism is written from an English perspective. But to do that again would be too predictable. And only to look to the postwar period would be too easy. The essence of Brutalism comes from looking at it in its many historical, geographical, cultural and material guises. Not as a corpse but as a living thing. One that this generation recognises. One that makes sense now, much as it might have done 100 years before Reyner Banham.

Because I build and I think about what might make buildings and spaces – and, indeed, landscapes – in certain ways Brutalist, I think it ought to be possible and, ultimately, more valuable to broaden the debate. We can no longer construct buildings in the manner in which we used to in the mid-20th century. Building technologies are much more complex now, reflecting the way in which we use the fabric of a building to temper its internal climate and energy consumption. So if we can’t replicate these buildings because we can’t construct them in the same rudimentary manner, then our generation must believe that there is more to Brutalism. Buildings have qualities that make them Brutalist. In this book I will try to convey what Brutalism is, not just what it was. How it looks. How it feels. How it is made. And, what it isn’t. This book, through a series of essays, speculates on the subject and offers various definitions, sometimes contradictory. It is not a grand thesis but a succession of plausible explanations.

Figure 1.7: A sketch of the Ibere Camargo Museum in Porto Alegre, Álvaro Siza, 1998–2008

Brutalism is construction. It is decoration. It can signify spiritualism. It is a medium for political and social expression. It suits certain climates. Sometimes, it just makes plain economic sense. Often, it seems to me to involve craft. At times, it seems to be the most natural response of the architect to the imperative to build at a certain point in the development of a civilisation.

Brutalism was given a voice, a position, by Alison and Peter Smithson’s polemic and subsequently by their friend, Reyner Banham. The Smithsons’ manifesto was published in 1952. Reyner Banham’s essay on the subject dates from 1955 and his book, which to a certain extent recast his idea of the movement, was published in 1966. This work, The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic?, charts the emergence of the New Brutalism between the early 1950s and the mid-1960s. My search for ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Dedication

- Prologue

- 1 Brutalism is not a Corpse

- 2 Ethic or Aesthetic?

- 3 Muck & Ore

- 4 Concrete

- 5 Brickalism

- 6 Craft

- 7 Precast

- 8 The Brutalist City

- 9 The Social Question

- 10 An Innocent State

- 11 The Sublime

- 12 The Brutalist Revival

- References

- Image Credits

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Redefining Brutalism by Simon Henley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.