eBook - ePub

Forgotten Voices

Power and Agency in Colonial and Postcolonial Libya

This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In Forgotten Voices, Ali Abdullatif Ahmida employs archival research, oral interviews and comparative analysis to rethink the history of colonial and nationalist categories and analyses of modern Libya.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Forgotten Voices by Ali Abdullatif Ahmida in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

FROM THE OTTOMANS TO THE ITALIANS: A POLITICAL ECONOMY APPROACH TO STATE FORMATION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY LIBYA

We can no longer be content with writing only the history of the victorious elites, or with detailing the subjugation of the dominated ethnic groups. Social historians and historical sociologists have shown that the common people were as much agents in historical process as they were its victims and silent witnesses.Eric W. Wolf, Europe and the People without History

It should be known that differences of conditions among people are the result of different ways in which they make their living.Ibn Khaldun, fourteenth-century historian

Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.Karl Marx, The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

This chapter reassesses the nature of the Ottoman state in Libya from 1835 to Italy's invasion of Libya in 1911. While most historians of that period, including Tahir Ahmad al-Zawi, Abdullah Ibrahim, and Lisa Anderson, argue that Tarabulus al-Gharb—the name of the country and city of Tripoli as nineteenth-century Libya was known—was a powerful central government in control of the hinterland by 1860,1 their analyses are based on dynastic or modernization theories. These theories ignore the salience of regional political economies. It is my contention that Libya's three major regions in the nineteenth century developed distinct political economies resulting from unique ecologies and the inability of the central state to control them. I argue that studies neglecting the significance of geography, commercial relations, and social classes are flawed because they limit our understanding of the dynamics of state formation and, consequently, the colonial period in Libya.

This chapter uses a political economy approach to state formation— an approach that emphasizes modes of production focusing on property relations, ecology, social classes, and ideology. It does not deny the impact of ideology, leadership, and nationalism, but interprets their development against a materialist background and assumes a mutual interaction between economy and ideology. To illustrate, three major issues will be addressed: (1)the rural–urban markets' integration in Tripolitania; (2) the decline of Fezzan's political economy in the second half of the last century; and (3) the rise of Cyrenaica's economy in spite of the marginality of its urban markets. This approach considers each region to have a political economy of its own, rather than assuming a single unit of analysis, the province of Ottoman Libya known as Tarabulus al-Gharb.

GEOGRAPHY: THE SOURCE OF AUTONOMY

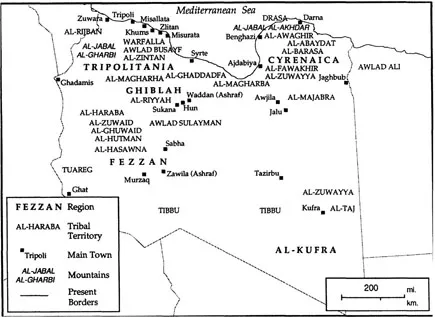

Tarabulus al-Gharb under Ottoman rule was made up of three distinct geographical regions: Tripolitania in the west, Fezzan in the south, and Cyrenaica in the east. As a desert country without rivers, the topography discouraged communication among the three regions. Even along parts of the Mediterranean coast in the Gulf of Syrte, the desert and the sea come face to face, forming a natural barrier between Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. Rainfall is scant and inconsistent. The coast of Tripolitania averages 300 mm annually, the Green Mountain of northern Cyrenaica receives 500 to 600 mm, and Fezzan and Southern Cyrenaica receive less than 10 mm.2 Only 5 percent of the entire country is suitable for cultivation, limiting settled agriculture to the coast of Tripolitania, parts of the Jfara plain and western mountains, the Marj plain in Cyrenaica, and the oases of Fezzan and Cyrenaica up to the middle of the century (see Figure 1.1). Two conclusions emerge from a consideration of Libyan geography. One is that pastoralism persisted from the time of the Hilali nomadic conquest in the eleventh century in response to natural ecological conditions (i.e., soil, rainfall, and climate), socioeconomic factors (i.e., a simple technology), and the inability of the tributary state to settle tribes prior to 1860.3 The second points to the significance of regionalism. The country's vast size and division by a large desert encouraged development of distinct regional characteristics, including unique urban markets and local political organizations. Far from being able to subdue hinterland tribes, which were mobile and militarized, the city of Tripoli could not control those who resisted or escaped into the desert.

The agropastoral economy was limited to herding animals and cultivating grain in rainy seasons but drought and famine occurred frequently.4 Trade across the Sahara with the more stable agrarian political economies of Europe, the Near East, and central and western Africa provided a more reliable source of income. Libya's strategic location as the closest region to western Africa across the Mediterranean meant that three of the five major trade routes went through Libya.5

Figure 1.1 Map of Libya: main towns, tribal territories, and regions (1910–1911).

Two routes cut through western Libya: one through Tripoli, Fezzan, Kawar, and Bornu, and one through Tripoli, Ghadamis, Ghat, Air, and Kano. The third crossed eastern Libya from Benghazi, through Kufra to Wadai.6

The trans-Sahara trade was established during the Roman Empire—a mercantile trade based on the exchange of luxury goods such as cloth, ivory, ostrich feathers, and gold as well as goatskins, guns, and slaves. European merchants sought markets for exporting cloth and guns; western African aristocracies desired these goods, and local Libyan economies profited by taxing the caravans to guarantee their free passage into tribal lands. Local tribesmen also worked as guides and benefited from other exchanges with the Europeans.

Organized regionally in Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica, the Sahara trade created strong alliances between the merchant class and tribal confederations such as the Qaramanli, Awlad Muhammad, and the Sanusiyya order, which came to dominate the trade. It flourished throughout western Libya until the 1880s, but as French and British colonialism advanced into western and central Africa, it began to decline. However, a third trade route through Cyrenaica continued to the turn of the twentieth century.7

The development of rural and urban markets in each region conditioned social and political loyalties. Tripolitanian urban markets were located mainly in the city of Tripoli (the center of the Sahara trade), and the agropastoral produced a surplus from rural areas and Fezzan.8 Fezzan also prospered as a market for the merchants of the Sahara trade, pushing the population of towns such as Murzaq, Ghadamis, Ghat, and Sukana to between 10,000 and 12,000 by the 1880s.9 Locally, the state of Awlad Muhammad emerged to organize the trade along the Sahara, which lasted from 1550 to 1813.10 Cyrenaica, however, had no real urban market. By 1860, Benghazi and Darnah each had a population of only 5,000.11 Through the end of the nineteenth century, the natural urban market for the tribes of the hinterland was northwestern Egypt.12

Cyrenaica's autonomy, beyond the reach of Tripoli, continued even after 1835 when the regency expanded its control into rural Tripolitania and Fezzan. Its independence was furthered by a strong militarized confederation of tribes, and the rise of the religion-based Sanusi order during the second half of the nineteenth century. The combination of religious, social, and commercial components, along with an already elaborate tribal organization, transformed Cyrenaica into a de facto state.13

A HISTORY OF TRIBUTARY RELATIONSHIPS

Early Ottoman society was dominated by tributary relationships. The Ottoman army conquered the region in 1551 and incorporated its tribes into a tributary system that supported the Ottoman regency's economy and dominance. The regency lived on taxes and tributes from urban and coastal areas, while strong militarized tribes collected tributes from peasants and client tribes—as in the case of the Mahamid in Tripolitania, the Awlad Sulayman in Fezzan, the Tuareg in southwest Fezzan, and the Sa'adi in Cyrenaica. In 1711, an ambitious Turkish military officer, Ahmad Qaramanli, founded an autonomous dynasty ruled by his descendants until 1835. Extending its authority over Fezzan, the Qaramanlis crushed the state of Awlad Muhammad in 1811 and profited from Fezzan's rich trading revenues.14

While the tributary system fed the rise of the Qaramanli, it also led to their downfall. Pressured in the 1820s by the French and British navies to stop imposing tributes on European ships in exchange for free passage, Yusuf Qaramanli began to borrow from the local and foreign traders. This policy led to the state's bankruptcy when Yusuf Qaramanli could not pay his debts to French and British traders. France and Britain responded by blockading Tripoli, forcing Qaramanli to sign treaties in 1830 and 1832, which not only called for paying his debts, but also guaranteed numerous privileges for European traders in the hinterland, including the ability to trade freely, have their own courts, and be exempted from paying major tributes to the state.15

In desperation, Yusuf Qaramanli imposed new taxes and lifted the exemption for paying taxes previously granted to the Cologhli class—descendants of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Turkish Janissary,16 who had become police and landlords. The Cologhli rebelled and rallied around his grandson Muhammad. Yusuf, who was old by 1832, resigned in favor of his son, Ali. The dynastic crisis turned into civil ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on the Transliteration

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 From the Ottomans to the Italians: A Political Economy Approach to State Formation in Nineteenth-Century Libya

- Chapter 2 The Rediscovery of the State of Awlad Muhammad: Sources and Significance, 1550-1813

- Chapter 3 From Tribe to Class: The Origins and the Politics of Resistance in Colonial Libya

- Chapter 4 Italian Fascism—Benign? Collective Amnesia Concerning Colonial Libya

- Chapter 5 Identity and Alienation in Postcolonial Libyan Literature: The Trilogy of Ahmad Ibrahim al-Faqih

- Chapter 6 The Jamahiriyya: Historical and Social Origins of a Populist State

- Glossary

- Notes

- Index