This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Manual of Ready-Mixed Concrete

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The new edition of this successful manual has been carefully revised throughout to take account of recent changes and to incorporate amendments required due to the publication of the revised BS 5328. This manual provides information on all aspects of the ready-mixed concrete industry, from the basic materials and their properties to the production,

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Manual of Ready-Mixed Concrete by R Anderson,J D Dewar,Heather McKee,Ian Treasaden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Methods & Materials. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1: TECHNOLOGY

Photograph courtesy RMC (UK) Ltd.

Introduction: History of ready-mixed concrete

The history of concrete in Britain [1, 2, 3] dates back to Roman times, but it was not until the 1930s that concrete was supplied ready-mixed in the UK. The constituent materials come from the earth in bulk, so concrete is most economically produced by handling the materials in bulk and mixing them in bulk. It was the advantages of scale and efficiency of mechanical mixing, plus improved control resulting from weighing the ingredients, that opened the way for the supply of concrete ready-mixed.

Ready-mixed concrete was patented in Germany in 1903, but the means of transporting it had not developed sufficiently well to enable the concept to be exploited. There were significant developments in the USA in the first quarter of the 20th century: the first delivery of ready-mixed concrete was made in Baltimore in 1913, and the transit-mixer was born in 1926.

In the UK it was not until 1930 that a Dane, K.O.Ammentorp [1], who had been involved in starting ready-mixed concrete in Copenhagen, emigrated to England, and in 1931 erected a plant at Bedfont, west of London, near what was to be eventually the site of Heathrow Airport. He suffered from planning delays, even in those days! The company, Ready Mixed Concrete Ltd, operated the plant housing a 2 cu yd central mixer, supplying six 1¾ cu yd capacity agitators (Fig. I.1), with an output of 40 cu yd/h. Aggregates were contained in a four-compartment bin of about 100 cu yd capacity. The cement was man-handled in bags.

At about the same time, the British Steel Piling Company became interested in transit-mixers and imported two from the USA. These had a mixing capacity of about 5 cu yd and were filled (with difficulty!) through a small hole in the back.

The next company to start was the Scientific Controlled Concrete Co Ltd of Staines, in 1934. They used Jaeger truckmixers, produced under licence by Ransome & Rapier Ltd. It appears that this firm operated for only a short time; some of their equipment was taken over by Truck Mixed Concrete (Southampton) Ltd and used in the Winchester Bypass. Next came Jaeger System Concrete Ltd, Glasgow, which much later was taken over by Tilcon Ltd. In 1936 the Express Supply Concrete Ltd was founded as a subsidiary of Balfour Beatty Ltd. It had two plants, the first at Paddington and the second at Alperton, with a total of 30 Jaeger truckmixers. At these plants the cement was delivered in metal 5-ton capacity bulk containers, which were lifted off the delivery lorries and emptied into bins by opening a gate at the bottom of the container. A pump was then used to elevate the cement from the ground bins to the bins over the cement weighing floor; a similar system is used for handling large plastic bags of bulk cement in some locations today. Another early producer from the aggregate side of the business was Trent Gravel Ltd, whose first plant was erected at Attenborough, near Nottingham, in 1939. At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, there were only six firms producing ready-mixed concrete in England and Scotland, one supplying concrete in agitators from a central mixer and the others using the truckmixer system.

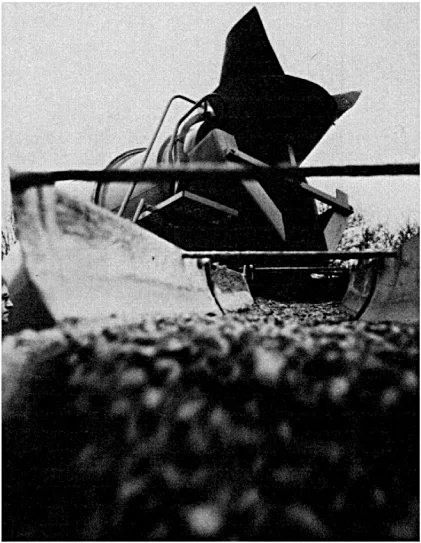

Figure I.1 Early towerplant with truckmixers and agitator. Courtesy of Tilcon Ltd

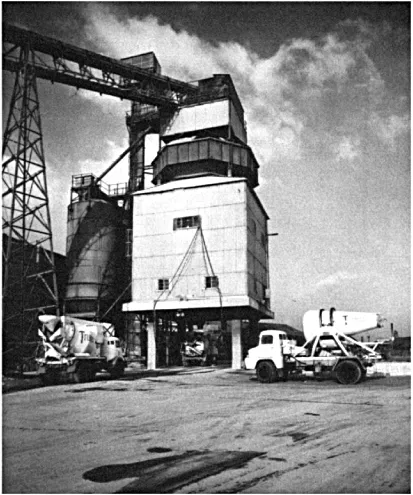

The handling of materials in bulk has dominated the design of ready-mixed concrete plants from the start. They were aligned initially to quarry practice, using drag-line excavators for aggregates and bucket elevators for cement. Long, high conveyors were used to elevate the aggregates to a height that allowed them to be stored above the weigh-scales and to be gravity-fed as required, from storage bin to weigh-hopper, from weigh-hopper to mixer and from mixer to the delivery vehicle. These tower plants (Fig. I.2) came into vogue in the late 1930s and after World War II. Some of them saw wartime service on airfield construction and other projects requiring large volumes of concrete. Tall plants were more acceptable in quarries and gravel pits but, with the requirement to provide plants nearer the markets for the concrete, plant designers had to provide units that were more environmentally acceptable.

The development of chevron conveyor belts meant that steeper angles could be used in elevating the aggregates, thus requiring less space. Separating the storage and weighing of aggregates from the storage and weighing of the cement meant that the height of plants could be considerably reduced. The split-level plants introduced in the late 1960s are still popular today and now dominate the industry, but the demands of planning authorities for lower-profile plants have led to the production of some even more compact plants. With compactness, plant transportability became viable, and now some ready-mixed concrete producers provide plants on major construction projects.

Ready-mixed concrete is a service as well as a product, and delivery techniques have developed along with the production side. In the 1930s, conical agitators and Jaeger truckmixers did yeoman service, although they were susceptible to the rear door opening in transit, resulting in premature discharge. Their use continued into the early 1950s, and as late as 1985 a site foreman in Central Scotland rang up the shipping office to ask for ‘a Jaeger of concrete’! The industry has generally encouraged the collection of concrete from its central mixer plants. Normal haulage lorries were frequent callers in the early days, then came tippers. Some companies operated telehoist tippers for a while, but it was the rotating drum mixer which prevailed and developed into the modern truckmixer which has really made the supply of ready-mixed concrete commercially viable.

Figure I.2 Conical agitator (1950s). Courtesy of C & CA and RMC Ltd

The current shape of truckmixer drum, relying on reversible action for loading and mixing then contra-rotating for discharging, developed into the late 1950s, so that by the 1980s the most common size, based on a three-axle chassis, mixes and transports six cubic metres of concrete. Larger units (carrying nearly 9 m3) and smaller ones (down to 2.5 m3) are in use, but the industry has accepted the 6 m3 truckmixer as the basic fleet unit.

The ready-mixed concrete industry has tended to outpace the construction industry in its willingness to innovate. Not all new ideas survived commercial pressures, mainly because purchasers were not always willing to pay a premium for an improvement in quality or service. Wet hoppers were supplied to sites into which the truckmixers could quickly discharge the concrete, allowing the contractor to collect and place the concrete at his own pace. Site conveyors were tried, and there are a few truckmixers operating with conveyors mounted on them. The early versions were heavy, resulting in a considerable reduction in the volume of concrete that could be carried in the drum. Developments using aluminium to lighten the conveyor have revived their popularity.

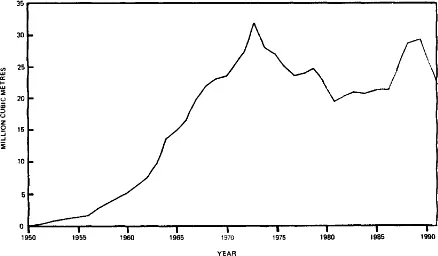

Figure I.3 Ready-mixed concrete in Britain. Courtesy of BRMCA and BACMI

There are even truckmixers with concrete pumps mounted on the chassis, but although such innovation is appreciated abroad, it has not gained favour in the UK. The ready-mixed concrete industry entered the concrete pumping business with enthusiasm, but lack of response from customers meant that the pumps were eventually sold off to a few concrete pumping specialists. In Britain, the percentage of ready-mixed concrete that is pumped is markedly lower than in the rest of Europe.

Cement weighing recorders were in vogue in the late 1960s, but the electromechanical gear did not stand up well to the dust-laden atmosphere, and 20 years had to elapse before solid-state electronics arrived to allow the manufacture of reliable processing, batching and recording equipment at economic prices. The processing systems have evolved from lever-arms, to servo-systems using compressed air, hydraulics and electronics, to computers and micro-processors, each step aimed at giving improved control of the whole production process.

The acceptance and growth of the ready-mixed concrete industry between the 1950s and 1974 was quite remarkable, with 31 million cubic metres per year being produced at the peak. The downturn in the construction industry was naturally reflected in the concrete production figures, and a period of rationalization and consolidation followed (Fig. I.3).

The short history of the ready-mixed industry has been dominated by the need to produce and deliver a high-quality product economically. The fact that most in-situ concrete is now supplied ready-mixed is a measure of how successful the industry has been, in terms of quality, service, and price to the customer.

Seeking to provide assurance of the quality of ready-mixed concrete has always been a requirement of the industry and was first manifested in the BRMCA Authorization Scheme, launched in 1968. This scheme introduced and enforced standards ensuring that each registered plant was able to produce concrete of the requisite quality and quantity. An additional section was added to the scheme in 1972, providing a very early approach to QA, by introducing auditing and certification of quality control procedures. In 1982, when BACMI was formed, it introduced a code of practice based on BS 5750 quality systems.

The Quality Scheme for Ready Mixed Concrete (QSRMC) was established in 1984 and was granted the ninth certificate accredited by the NACCB. With its independent Governing Board regulations based...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Part 1: Technology

- Part 2 Practice

- Appendix 1: QSRMC technical regulations

- Appendix 2: Conversion factors

- Appendix 3: Designated mixes in accordance with BS 5328: Part 2 Section 5

- References

- References to standards