![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Stoicism, Language, and Freedom

Kurt Lampe

1 The Meaning(s) of the Stoic Tradition

What is the significance of the Stoic tradition? That, of course, is an unwieldy question: the concepts, arguments, doctrines, mental and practical techniques, and everything else that travels under the label “Stoicism” have meant different things to different people. Today we have an increasingly detailed understanding of the aspects of ancient Stoic theory preserved by surviving ancient Greek and Roman sources. The academic study of this evidence, which until the 1980s was concentrated in German and French scholarship, is now flourishing in anglophone universities as well. There is also a growing body of research about the reception of Stoicism from antiquity until today (e.g., Spanneut 1973; Colish 1990; Neymeyr, Schmidt, and Zimmerman 2008; Sellars 2016). Perhaps more surprisingly, in the last decade “modern Stoicism” has become a powerful international movement, bringing together scholars of antiquity, psychotherapists (especially from cognitive-behavioral backgrounds), and a broad public interested in living philosophically.1

Dwelling briefly on this movement will shed some light on how the reception of Stoicism in “continental (European) philosophy” enriches its significance. While it is hazardous to generalize, the following quotation from the front cover of Donald Robertson’s excellent Stoicism and the Art of Happiness is both concise and representative: “What is Stoicism? Practical wisdom and resilience building techniques. Take control—understand what you can and can’t change” (2013). Let me expand this a bit. The modern Stoic is enjoined to become mindful of the contents of her consciousness (e.g., words, images, sensory and bodily feelings, emotions, and impulses), to articulate these in propositional form, to weigh these propositions against a series of guidelines (e.g., that we must focus on what we can control, namely our thoughts, and that behaving virtuously is more satisfying and valuable than wealth, status, or any other goals external to our behavior), to harmonize and systematize them, and in this way to view herself as someone progressing toward greater happiness, goodness, and concord with other people and the world (cf. Robertson 2013: 10). There is no doubt that this approach is well grounded in the ancient texts and accurately captures core intentions of many ancient practitioners. However, we should also remark that modern Stoics emphasize some aspects of the ancient evidence and downplay or repudiate others—avowedly and deliberately so, in fact (Vernon and LeBon 2014; Chakrapani 2018). For this chapter’s purposes, it suffices to mention two of these partialities. The first is that, in proclaiming humankind’s “natural rationality,” they set aside the myriad epistemological, psychological, sociopolitical, and metaphysical questions raised by the endeavor to express truthfully in language the content of thought and the structure of reality.2 The second is that, in declaring that our thoughts are “under our control,” they beg questions about both external and internal determinism and freedom.3

Now contrast the following passage from a section called “In the Garden of Epictetus” in The Education of the Stoic by the Portuguese author Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935):

“The pleasant sight of these fruits and the coolness given off by these leafy trees are yet other solicitations of nature,” said the Master, “encouraging us to abandon ourselves to the higher delights of a serene mind. . . . Sit still with me, and meditate on how useless effort us, how alien the will, and on how our very meditation is no more useful than effort, and no more our own than the will.” (Pessoa 2005: 51)

Since Pessoa (or rather his heteronym, the Baron of Teive) puts these words into Epictetus’s mouth, he implicitly questions to what extent anything is “under our control,” including our thoughts: “Our very meditation,” he muses, “is . . . no more our own than the will.” We could relate this to the ancient Stoics’ own attempts, given their commitment to universal causal determinism, to explain in what sense our decisions belong to us (LS 55, 62; cf. Bobzien 1998: 234–411). Pessoa’s Epictetus also doubts whether we can know or express any truths, which is one reason he considers the very meditation he performs “useless.” Later he explains that we can neither know nature, despite its tantalizing “solicitations,” nor express what we think (2005: 52). Once again, this can be related to ancient Stoic doctrines: their standards of knowledge and correct reasoning are so lofty they have to defend the possibility of their attainment (as we can now read in what may be Chrysippus’s own words [Alessandrelli and Ranocchia 2017]).4 So the Baudelairean attitude of Pessoa’s Epictetus, though antithetical to that of the ancient Stoics, can neverthel ess be read as an intelligible reaction to their teachings, albeit one colored by personal idiosyncrasies and a specific moment in literary history.5

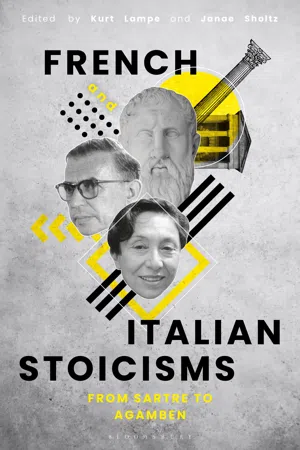

Pessoa was a younger contemporary of Jean-Paul Sartre, the earliest modern philosopher addressed in the present volume, and features prominently in Handbook of Inaesthetics by Alain Badiou, at the opposite chronological end of our coverage. The two broad themes I have just identified in the quotation from his work, which I shall encapsulate under the headings “language” and “freedom,” recur frequently in French and Italian reception of Stoicism. This reception tradition, it should be emphasized, is a complement rather than a competitor to modern Stoicism. One of the French authors concerned, Pierre Hadot, is frequently cited in modern Stoic literature. As Matthew Sharpe elucidates, Hadot’s readings incorporate both prior German and French scholarship and a range of philosophical influences (Sharpe, Ch. 13). Nevertheless, it remains true that continental philosophers tend to develop the meaning of the ancient evidence with greater creative latitude than modern Stoics. On the one hand, they explain aspects of Stoic practice differently than the practitioners themselves, and in this respect expand our understanding of the Stoic life. On the other, they discover significance in theorems that the original theorists would probably disavow, and in that respect envisage ways of living “Stoicism” quite different from those practiced in the ancient world or the mainstream of the modern Stoic movement.

I will not attempt to survey the chapters to come in the remainder of this introduction. Instead, I will selectively use and supplement their research and arguments in order to comment briefly on how modern French and Italian philosophers’ engagement with Stoicism allows them to raise subtle and important questions about language and freedom.

2 Language

The foundational figure for continental responses to Stoic philosophy of language is Émile Bréhier (1876–1952), chair of the History of Ancient and Modern Philosophy at the Sorbonne and successor to Henri Bergson at the Académie des sciences morales et politiques. Bréhier’s research interests were extremely far ranging, but Stoicism particularly fascinated him both intellectually and practically, as Henri-Charles Puech eulogized:

This intransigent rationality, which was nevertheless life-affirming and profoundly human, this austere discipline of self-mastery, this ideal of wisdom founded on the accord of philosophical autonomy with the rhythm of the universe, inspired in him both sympathy and admiration. (1952: xxvi)6

Bréhier’s doctoral thèse complementaire, the first edition of which reached publication in 1907 (third edition 1962), was on La théorie des incorporels dans l’ancien stoïcisme (“The Theory of Incorporeals in Ancient Stoicism”)—a topic which had begun attracting attention in the 1880s, and which von Arnim’s collection of fragments in 1903–5 made substantially more accessible.7 The metaphysics of “sayables” (lekta) feature prominently here, as indeed in Wolfhart Totschnig’s recent defence of Bréhier’s core position (Totschnig 2013). But Bréhier’s formulations have generated echoes far beyond specialist scholarship. Consider the terminology he uses to highlight the Stoic distinction between bodies, which are beings and have causal power, and the effects of bodies, which are nonbeing, incorporeal sayables:

These results of the action of beings, which the Stoics were perhaps the first to perceive in this form, are what we today would call “facts” or “events” (des faits ou des événements): a bastard concept that is neither that of a being nor of one of its properties, but what is said and asserted about being. (1962: 13)

Note two aspects of Bréhier’s interpretation of Stoic sayables. First, he problematizes their relationship with the bodies that cause them (when they are conceived as effects, LS 55A-D) or to which they refer (when they are conceived as the content of thoughts, LS 33). We will see below that this problem expands to encompass their relation to the signifiers that express them, the speech acts that enunciate them, and the speakers who think and say them. Second, he elevates this problem to the status of a metaphysical principle. It is in this connection that he speaks of “‘facts’ or ‘events,’” which are caused by beings, yet whose connection to those beings is unstable: they “play” on the “surface” of being (1962: 12–13, 60–3). This way of presenting the Stoic theory of sayables has ethical and political consequences, as the evental metaphysics of Deleuze, Badiou, and other contemporary continental philosophers demonstrates. Although these aspects are tightly intertwined, for the sake of exposition I will present them separately.

Let me begin with language and the event. It is well known that Gilles Deleuze took inspiration from Bréhier’s interpretation of the Stoic theory of sayables when elaborating his metaphysics of the chaosmic Event in The Logic of Sense, which coordinates ideal significations, bodily intensities, and enunciative attitudes.8 (Deleuze was also influenced by Bréhier’s successor, Victor Goldschmidt, on whom see further below.) It has not been recognized until now that Sartre had preceded Deleuze in this respect, as Laurent and Suzanne Husson demonstrate in this volume. Sartre enthusiastically followed Bréhier’s lectures at the Sorbonne, and his loan record at the École Normal...