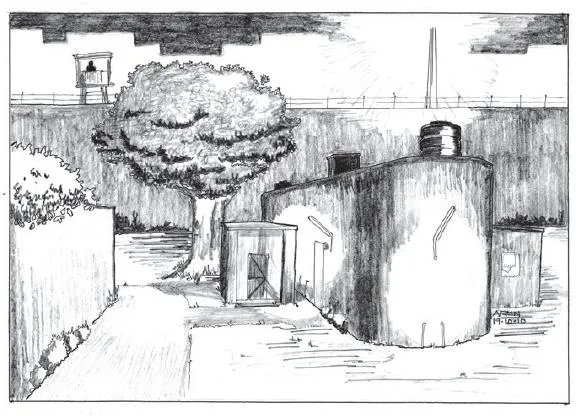

The Anda

Saturday, September 8, 2007

Legally I have been implicated in six cases until now. I don’t think this number will increase. However, due to the arrest of two more political dissenters [Sridhar Srinivasan and Vernon Gonsalves, both in their mid-fifties] in Mumbai who the state now regularly refers to as Maoists, my name has once again begun to appear in the newspapers. Guess this is going to be a regular feature; I might as well start getting accustomed to it.

Your letter mentions how this year has taken a heavy toll on the entire family. This is not far from the truth. However, remember the strong get through difficulties, victorious and even stronger. It is the weak who collapse and give up hope. I don’t think you have taught me to be the latter. Keep writing, your letters help.

Letters to my family were not only a medium for communication but also a pretext for mutual consolation. On the arrival of my messages, my wife would come to Bandra almost immediately to meet with Mom and Dad. My elder brother and sister who lived nearby would drop by too and my letter would invariably result in a family discussion. The children playing in the adjoining room were oblivious to the problems the family was facing.

Bandra, a former suburb of Mumbai but now part of the expanding city, was the place of my birth and where I grew up. As a schoolboy, my worldview was limited by the boundaries of this suburb, a righteous Christian upbringing, and the impractical, lofty aspirations of a typical middle-class family. I had my first brush with social activism as a student at Mumbai’s St. Xavier’s College in the early nineties. I’d organized camps in villages and welfare projects for the underprivileged. Through such camps I became exposed to the harsh realities of India and the limitations of charity. I clearly recollect an encounter at a camp in Talasari in Thane district in 1991 where we spent our days enthusiastically building a road for the villagers. In the evenings, we would chat with the residents or have cultural performances for their entertainment and education. When I visited a house in the Dalit pada [hamlet], one resident asked me why we were holding the camp. I proudly told him it was to build a road so that they could reach the market more easily. He told me that the location of the road we were constructing would allow only the sarpanch and other members of upper-caste families to get to the market. The majority of the villagers, especially the poor and the Dalits, would still use the old kuccha road. I was unintentionally deepening an already existing social division.

Indian society, I realized that day, was fractured by class and caste and riddled with innumerable contradictions. Power vested in the economic and social elite, and the benefits of development flowed disproportionately to them. Unless these structures were changed, charity would be meaningless.

The communal riots of 1992–1993 that followed the destruction of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya really shook me up. The riots had caused thousands of Muslims to be displaced in their own city. I was in my final year of college, soon to become a Mathematics graduate. A group of us from St. Xavier’s decided to work with a housing rights organization that was running relief camps for Muslims. The callousness of the state, which allowed the Shiv Sena to conduct this pogrom unimpeded, could not have been on better display. The Shiv Sena and other Hindu fundamentalist mobs acquired voter lists so that they could systematically target Muslims, while the police threatened to fire on any sign of resistance from the victims. Thousands of Muslim houses were burned and the residents were shifted to relief camps and community centers. In such a charged atmosphere, to speak of fighting the oppressors would be seen as an act of communal violence. The least we could do was collect clothes and funds to help the victims put their lives back together.

Kartik Pannalal, a former student of my college, was a friend during these times. He had left his family’s diamond business to work to build a just society. He regularly visited St. Xavier’s to organize the college canteen workers who were agitating for their rights, including the right to unionize. He helped them stage several strikes and we tried to get the students to support them. I’d spent long days in college involving myself in the lives of the workers, having heated discussions with student union leaders and then in the evening, chatting with the workers and discussing working-class issues over endless cups of chai.

Through Kartik, I came to realize that there were many more like us—organizations and movements across the country and around the world that were working with the same ideals. I joined one such revolutionary student organization, the Vidyarthi Pragati Sanghatana (VPS), which had units in several colleges. It had student committees in Mumbai, Nagpur, Nashik, and Chandrapur, and also a state-level committee. The VPS was a member of a national organization called the All India Revolutionary Students’ Federation. The activities of the VPS centered on the struggle for a democratic, scientific, and egalitarian education system. But education, like all other aspects of society, could not be transformed in isolation. Hence, we would strive to build and support other struggles aiming at the radical transformation of class and caste society.

Even though the Western world was tom-tomming its so-called victory over Marxism as the Soviet Union disintegrated, I was getting attracted to the ideology. Stories of the French Revolution as well as the Russian and Chinese revolutions impressed on me the true potential of the oppressed to effect social change. Society needed qualitative leaps or revolutions to bring about change and the present world order wasn’t the end of history. Unfortunately, my co-traveler on these intellectual journeys, Kartik, died in a road accident in Delhi in June 1997. He was on his way back from a fact-finding enquiry into military excesses in the Kashmir Valley. He was only twenty-nine. Society had lost a committed civil liberties activist and I, a great friend.

While in the VPS, I had the opportunity to meet with youth from diverse backgrounds, especially from the working class and lower castes. Many of them inspired me with their talent and zeal to change society. The more oppressed they were, the greater their commitment. We organized many struggles against fee hikes and against a proposed university bill that would do away with elections to student unions and select representatives based on academic merit. But the bill was enacted in 1994 and landed a major blow to student politics in Mumbai. Student unions became student councils and were deprived of any autonomy.

The VPS also managed to highlight the corruption of Dr. S. D. Karnik, the Pro Vice-Chancellor of Bombay University (now known as the University of Mumbai) and successfully organized students to demand his ouster in 1995. We organized annual “go-to-the-villages” campaigns across western India to help the dispossessed assert their rights. In the Nashik campaign, we supplemented the efforts of tribals who were organizing against the atrocities of the Forest Department. In Dabhol, we took part in the struggle of villagers who were resisting the Enron power project. In Umergaon, Gujarat, it was the fisherfolk who were protesting their imminent displacement by a gigantic, upcoming port.

Looking at all these struggles up close made me aware of the true potential of peoples’ movements as agencies of change. Real change meant questioning the unequal relations of power and organizing the people to claim their rights themselves. These struggles showed me how the state was the principal tool of oppression. The state institutionalized oppression. The violence it perpetrated crushed any challenge. As a result, many sincere peoples’ movements such as the Naxalite and secessionist movements in Kashmir and the Northeast had to evolve militantly in order to survive. In such a situation, I could not condemn the militancy of these groups. It had a historical and political context.

After college, I continued for a couple of years in the student movement and later, I joined Naujawan Bharat Sabha (NBS), a youth organization that got its name from a body founded in 1926 by the revolutionary freedom fighter Shaheed Bhagat Singh. In the late nineties, Naujawan Bharat Sabha was involved in the struggles of Mumbai slum dwellers protesting the demolitions of their homes. At that time, the city was witnessing a series of slum demolitions as a result of the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme (SRS) announced by the newly elected Shiv Sena government. It allowed developers to build luxury towers on slum land. The timing of this scheme coincided with a spike in property prices, so construction companies were eager to get to work as soon as possible. Slum dwellers took to the streets. We helped mobilize them and organized agitations along with many other groups. I stayed in these bastis for weeks. Organizing struggles, I realized, was not only compelling but also absorbing.

This was also the time when globalization began showing its ugly face and people all over the world began to take to the streets. The Seattle movement in 1999 and the militant Genoa mobilizations in 2001 against the World Trade Organization and G8 summits inspired us. Many of us in the city and in Maharashtra were keen on building similar, broad anticapitalist peoples’ movements. To do this, organizations and activists across the state had to be contacted and consulted. I involved myself in this task.

After the World Trade Center attack in New York in 2001, however, there was a change in the way peoples’ movements came to be perceived. The so-called “War Against Terror” made security a key aspect of state policy. In India, special laws were promulgated to squash inconvenient truths. Organizations were banned, opinions were criminalized, and social movements were branded as terrorist. Those who supported the right to self-determination of Kashmiris or of the peoples of the Northeast were termed “antinational.” Muslims who battled against Hindutva were termed “jihadis.” Those of us Marxists who worked to organize tribals or the oppressed were easily labeled “left-wing extremists.” The VPS, Naujawan Bharat Sabha, and other organizations I had worked with were systematically targeted. Just as it had in colonial times, the Naujawan Bharat Sabha again faced a ban.

In 2005, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh declared that Maoists were “India’s greatest internal security threat.” Some were “encountered” or “disappeared,” while others were arrested. In places like Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, or Vidarbha in Maharashtra, left-leaning political organizations were branded as Maoist and dealt with accordingly. In the months before my detention, many Dalit activists in Nagpur had been arrested on charges of radicalizing the Ambedkarite movement by infusing it with the politics of Naxalism. Some of them had previously been associated with the Nagpur unit of the VPS. All this meant that I wasn’t entirely unprepared to be arrested. Still, even though I’d contemplated this hypothetical situation, I wasn’t completely prepared to become a target of these excesses myself—to be arrested, tortured, implicated in false cases with fabricated evidence and to be locked away in prison for several years.

* * *

September 8, 2007 (cont.)

The old TIME magazines you sent were great. I also received the sweaters you had sent. The other clothes were loose. I have probably lost weight during police custody. I now eat dinner at 6:30 p.m. and I am off to sleep by 8 p.m.—can’t afford to allow the food to get any colder. My court visits continue. However, since many of the dates overlap, the frequency of these trips has reduced. I have run short of some good reading material. Try sending me some by post or whenever someone comes next.

My letters from prison had to pass through various layers of officialdom before they finally reached the post box. The guards would first make an entry in their register before sending the letter to the jailer in charge of the barrack. An inquisitive guard would always comment on its contents, especially if the letter was in English, I suspect to prove his own command over the language. The mention of an inmate in my letter could very well be the next topic of gossip or the cause of the next argument, so I had to be careful. The jailer would then censor the letter. Material that criticized the administration was obviously discouraged. We would be summoned and lectured on how such writing would incite prison disrespect and indiscipline. Disparaging remarks about the jailer could not even be contemplated. In our high-profile case, photocopies of our letters were filed away, to be shown periodically to the Anti-Naxal Department of the police. Once, the jailer insisted I remove criticism of the prime minister from a letter. “Rule 12 of the Prison Manual states that ‘political matters are not to be discharged at interviews’ and in letters,” he asserted. Hence, comments in letters had to be framed with some deliberation. I had to stick to the facts as far as possible. But how could I hide my emotions? That is what my family wanted to hear. Initially, I used cryptic terminology, but as the years passed by and I grew familiar with the system, I began to disregard the snooping eyes.

The two-star jailer of the anda was Nagdev Pawar. His seniority in the department should have given him the post of a three-star, or senior jailer, but he had once been suspended because he’d been accused of beating an inmate to death. This, I found out, was a regular practice in the prison department. Almost all officers had been accused of misdeeds at some point in their careers. Corruption and negligence in duty were the most common charges. Allegations such as torture and beatings would rarely result in an officer being suspended unless this had led to the death of a prisoner. Even if he was suspended, it barely seemed to matter. The case would continue for years and, after being acquitted, the officer would be reinstated with full back pay. Moreover, because of a shortage of jail staff, the administration would often summon staff back to duty even during their period of suspension.

Nagdev Pawar’s de facto seniority in the Nagpur Central Jail gave him additional responsibilities and also immunity. He’d visit the anda only before the superintendent’s weekly round. Strolling in, with his pants pulled up almost to his chest, he would casually enquire if we had any requests or complaints. He had a very strange way of dealing with our grievances. Whenever we complained of the poor food or the fact that the same vegetables were served at every meal for days on end, he’d reply that he had to cope with the same situation in his sarkari quarters. His experience from all his years of dealing with inmates had obviously taught him that since he couldn’t solve our problems, he’d be better off claiming to share them. Either this was true, or he was actually skimming off our prison rations.

As the four of us coaccused (or numberkaari, in jail terminology) were all socially aware, we were quick to respond and react to the absurdities and injustices that were commonplace in the prison system. This is what we all had done earlier and it united us behind bars. One of our first struggles with Nagdev Pawar and the prison administration was to obtain a copy of the Prison Manual, which determined every detail of how life should be conducted in jail. At first, the administration ignored our plea and later claimed that they didn’t actually possess a copy. This was ridiculous, the Prison Manual was their rule book after all. Like the Penal Code and Criminal Procedure, rules for prison administration were first codified by the British in the latter part of the nineteenth century. The Prisons Act of 1894, adopted to keep unruly natives under control, remains the guiding protocol for prison administration long after 1947. After the Constitution came into effect in 1950, the administration of prisons became the responsibility of state governments. In the years that followed, the Maharashtra government enacted numerous new prison rules. These, along with the Indian Prisons Act, are collectively known as the Maharashtra Prison Manual. British jail officials were known to have denied prisoners any access to the Prison Manual. Nagdev Pawar and Co. seemed to want to continue this colonial legacy by denying us a copy of the rule book.

* * *

Life in the anda makes one crave for news of the outside. There was one particular spot in the anda where we could view a few leaves of the trees beyond the wall. Instinctively, that became the spot where the four of us numberkaari gathered to chat before bandi—just before sunset—when all the barracks were locked for the night. In the absence of an alternative, frequently narrated stories became a source of great amusement. We would try to start a conversation with Chandu of the danda kamaan who came to clean the toilets, or members of the jhadu kamaan who came to fill water in our peepas—the fifteen-liter tin cans in our cells—when the regular supply failed. The jhadu kamaan, if offered a beedi, would chat until they were exhausted. To encourage these precious snatches of conversation, we began purchasing smokes from the prison canteen.

Lean and middle-aged Chandu would, every morning after the opening of bandi, waddle in with a garbage pail in one hand and a broom in the other to empty the jhootan [scraps of food leftover]. He would bring life into the anda every morning with his rustic chatter, filling us with news of barrack life the night before. On his evening trips, just before bandi, he would be much more relaxed and had longer to chat, as his danda kamaan team were the last to be locked up after they’d cleaned the prison-yard toilets. Chandu was from a village in Nagpur district and had been convicted for a murder he had committed on behalf of a friend. Though the frie...