eBook - ePub

Central Banking in Developing Countries

Objectives, Activities and Independence

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Central Banking in Developing Countries

Objectives, Activities and Independence

About this book

This book examines the current state of central banking in 44 developing countries. The authors analyse the banks' achievement in their primary objective of price stability and discuss the reasons behind the general lack of success. The book covers: * government financing * foreign exchange systems * domestic banking systems. Rich in data, the book

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

This book examines central banking in 44 developing countries that appear to be reasonably representative of central banks in developing countries as a whole. The study starts by examining the achievement of this group of central banks in maintaining price stability, their primary stated objective. Because success has been elusive, we then examine the relationship between central banks and government financing, as fiscal exigencies certainly explain a considerable part of the difficulties central banks have faced in their price stability objectives. This analysis is followed by an examination of central banking activities in the foreign exchange markets, including the nature of the foreign exchange regime, why such a regime was chosen and what functions central banks perform in this area. The remaining chapters of the book examine the relationships between the central bank and the private sector. Here we cover both the implementation of monetary policy and the prudential regulation and supervision of the financial system. In all three general areas—government financing, foreign exchange systems and the domestic banking system—we find that central banks in developing countries face environments that differ radically from the environments faced by central banks in the richer OECD countries. Nevertheless, we detect some distinct changes over the past 25 years.

This study, undertaken at the invitation of the Bank of England (BoE) for its Symposium on Central Banking in Developing Countries on 9 June 1995, relies on several sources of information. Most of the quantitative work is based on data from International Financial Statistics (IFS) and the World Bank’s Socioeconomic Time-series Access and Retrieval System: World Tables. In addition to publicly available data from the IFS and World Tables, we supplemented the factual basis for this book through responses to a questionnaire, which we devised, on a variety of central banking topics. The Bank of England sent the questionnaire to and collected the responses from the central bank governors who were invited to the Symposium. This questionnaire is reproduced in Appendix 1 and the countries to which it was sent are listed in Table 1.1.1 Clearly, these countries, referred to hereafter as the BoE group, were not randomly selected; the group consists predominantly of Commonwealth countries and under-represents Francophone and East Asian countries.

The typical central bank of a developing country operates under several conditions that contrast with those in the OECD countries.2 First and foremost, central banks in developing countries tend to dominate their countries’ financial sectors to a larger extent than do central banks in the OECD countries. Rather than acting as primus interpares, the typical developing country central bank dictates the terms and conditions under which other financial institutions may operate. Partly as a consequence of this role, central banks in these countries have assumed an enhanced responsibility for fostering the structural development of their financial systems, a subject covered in Chapter 5.

Table 1.1 The Bank of England group

At least until very recently, market forces were fragile or even nonexistent in many developing countries, in part due to financial repression. Hence, developing country central banks were relieved from the attendant problems of operating within a market framework. However, thriving parallel and noninstitutional markets circumvented controls over the formal financial system. In recent years, therefore, most central banks in developing countries have been struggling to move from a regulatory or control mode, which was becoming increasingly ineffective, to indirect market-based techniques of implementing monetary policy, as discussed in Chapter 5.

Table 1.2 compares some salient variables across developing and OECD countries. The sample consists of 122 developing countries and 20 OECD countries, all countries for which reasonably comprehensive data sets are available from IFS and World Tables.3 The 122 developing countries are split into two groups: a control group of 79 countries and 43 countries of the BoE group.4

Table 1.2 shows that the ratio of money (M2) to GDP (M/Y) in developing countries is barely above one-half of the money/ income ratio in OECD countries.

At the same time, however, the data in Table 1.2 support our assertion that central banks dominate their financial systems to a considerably greater extent in developing countries than they do in the OECD countries. Specifically:

- The ratio of central bank liabilities in the form of reserve money (currency in circulation plus bank deposits at the central bank) to M2 (H/M) is almost three times higher in developing countries than in the OECD countries.5

- The ratio of bank reserves to bank deposits (R/D) is five times higher in developing countries than in the OECD countries.

- M2 represents a larger percentage of total financial assets in developing countries than in the OECD countries.

Table 1.2 also shows, somewhat surprisingly, that while developing countries differ from OECD countries the BoE group possesses the same characteristics as the developing country population as a whole. For example, in both the BoE group and all other developing countries:

Table 1.2 Some macroeconomic and monetary characteristics of developing and OECD countries, 1979-93 (per cent)

| Variable | Developing | Control group (79) BoE group (43) | OECDcounnies |

| countries (122) | (20) |

GR/Y Government revenue/GDP.DT/YForeign debt/GDP. PCY 1992 per capita income in US dollars (exchange rate based, geometric averages).

- Inflation (INF) averaged 30 per cent over past 15 years.

- The ratio of money to income (M/Y) averaged 40 per cent.

- The ratio of reserve money to M2 (H/M) averaged 40 per cent.

- The ratio of bank reserves to deposits (R/D) averaged 25 per cent.

- Government deficits averaged 6 per cent of GDP (-GS/Y).

- Foreign debt averaged 70 per cent of GDP (DT/Y).

In other words, the BoE group appears to represent developing countries reasonably well. We hope, therefore, that our findings from this group apply more broadly to developing countries in general.

The macroeconomic data for the BoE group presented in Table 1.2 exhibit some simple statistical associations:6.

- The ratio of reserve money to M2 (H/M) is positively related to inflation (INF) and government deficits (-GS/Y).

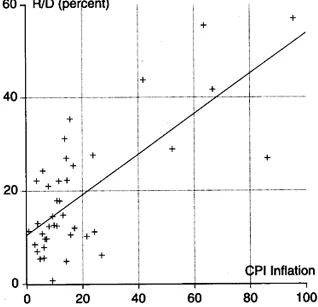

- The ratio of bank reserves to deposits (R/D) is positively related to inflation (Figure 1.1) and to government deficits (-GS/Y).

- Inflation (INF) is positively related to the proportion of government borrowing met by the central bank (CBCG) (Figure 1.2) and to the proportion of government borrowing in total domestic credit (CGDC).

- Economic growth (YG) is negatively related to the proportion of government borrowing met by the central bank (CBCG) (Figure 1.3 ) and to the proportion of government borrowing in total domestic credit (CGDC).

- Economic growth (YG) is negatively related to both government deficits (-GS/ Y) (Figure 1.4) and foreign debt (DT/Y). David Ricardo (1817) explains why foreign debt accumulation is inimical to growth by encouraging capital flight.7

- Inflation (INF) is negatively related to economic growth (YG).

Most of these relationships are relevant, either directly or indirectly, to central banking and monetary policy implementation in developing countries. They are therefore considered again in more detail in appropriate chapters later in this book.8 While Table 1.2 demonstrates that developing countries differ from OECD countries in some important respects, it also suggests the BoE group does not diverge greatly from the developing country population as a whole, at least in terms of these variables. In other words, the BoE group appears to represent developing countries reasonably well. Nevertheless, the BoE group is far from homogeneous, another accurate reflection of developing countries as a whole. Appendix 2 provides data for individual countries in this group on the same basis as Table 1.2. Average rates of economic growth over the period 1979-93 range from -2.3 per cent in Guyana to 10.2 per cent in Botswana. Inflation averaged 0. 7 per cent in Saudi Arabia compared with 556 per cent in Argentina. Per capita income comparisons also reveal large disparities. However, the results vary enormously depending on the basis used for such comparisons. For this reason, we present three alternative sources of per capita income estimates for the BoE group in Appendix 3.9

Figure 1.1 Ratio of reserve money to deposits and inflation as Table 1.2. Average rates of economic growth over the

When we look at trends over the past 15 years, we detect a shift from a dirigiste environment of administratively fixed interest rates, credit rationing and directed credit policies towards financial liberalisation and the use of indirect market-based techniques of monetary control. Table 1.3 presents the results of splitting the observation period into three five-year sections. The data are not strictly comparable to those in Table 1.2 because only countries with observations for all three periods are used in calculating the averages presented in Table 1.3. Table 1.3 shows that while growth rates and money/income ratios have risen over the past 15 years in the BoE group, inflation has risen. When Argentina is excluded, average inflation for the remaining countries remained virtually unchanged at around 20 per cent. The financial-fiscal variables, however, indicate a consistent trend:

When we look at trends over the past 15 years, we detect a shift from a dirigiste environment of administratively fixed interest rates, credit rationing and directed credit policies towards financial liberalisation and the use of indirect market-based techniques of monetary control. Table 1.3 presents the results of splitting the observation period into three five-year sections. The data are not strictly comparable to ...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- TABLES

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 1: INTRODUCTION

- 2: PRICE STABILITY, MONETARY EXPANSION AND OUTPUT GROWTH

- 3: THE CENTRAL BANK AND THE GOVERNMENT

- 4: CENTRAL BANKS’ EXTERNAL ACTIVITIES

- 5: THE CENTRAL BANK AND THE PRIVATE SECTOR

- 6: REGULATION AND SUPERVISION

- 7: THE STATUS OF THE CENTRAL BANK

- 8: CONCLUSION

- APPENDIX 1: CENTRAL BANK QUESTIONNAIRE

- APPENDIX 2: SOME MACROECONOMIC AND MONETARY CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND GROUP,1979–93(PERCENT)

- APPENDIX 3: ALTERNATIVE MEASURES OF PER CAPITA INCOME IN US DOLLARS

- APPENDIX 4:

- APPENDIX 5: ESTIMATED REVENUE FROM FINANCIAL REPRESSION IN THE BANK OF ENGLAND GROUP, 1979–93 (PER CENT)

- SYMPOSIUM PROCEEDINGS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Central Banking in Developing Countries by Álvaro Almeida,Maxwell J. Fry,Charles Goodhart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.