This is a test

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Commodities in an Age of Empire

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is a novel interpretation of the relationship between consumerism, commercialism, and imperialism during the first empire building era of America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Unlike other empires in history, which were typically built on military power, the first American empire was primarily a commercial one

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access American Commodities in an Age of Empire by Mona Domosh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Human Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Selling Civilization

Its [the Centennial Exhibition’s] object is to bring before the world the resources of the people of our nation in friendly competition with those of other nations. In its results it will test the relative advantage of a government by the people over imperial governments, for the successful development of the great works of peace. The vast preparations being made for our Exhibition by foreign nations realizes to us the necessity of leaving nothing undone which in these respects will determine, on our own soil, our real position of leadership in the world.

— International Exhibition (1875)

We need at this juncture to reintroduce the question of diversity in the making of the North American informal empire. In part, this can be accomplished by considering other cultural mediators whose texts and visions have left an important and enduring imprint in the metanarratives of U.S. expansionism.

—Ricardo D. Salvatore, “The Enterprise of Knowledge: Representational Machines of Informal Empire,” in Close Encounters of Empire: Writing the Cultural History of U.S.-Latin American Relations, ed. Gilbert M. Joseph, Catherine C. Legrand and Ricardo D. Salvatore (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998),70.

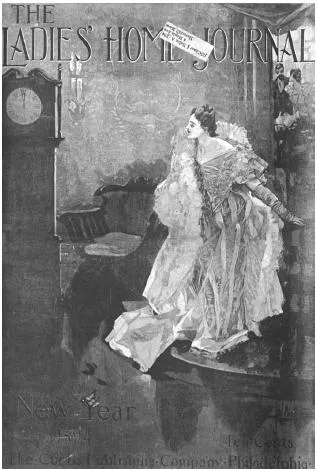

Commercial Geography Lessons

When Mrs. Helen A. Chase of Haverhill, Massachusetts, thumbed through her February 1894 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal (see Figure 1.1), scanning the various articles, advice columns, and advertisements for hints about how to decorate her home, clothe her family, and prepare dinner that night, she was performing a ritual of middleclass American domesticity that taught her about the world. By 1894, many American companies, particularly those that manufactured mass-produced commodities, were selling their products overseas, and they used this association to the foreign to promote their products at home. In this way, people like Mrs. Chase learned about other peoples and other places. They were participants in an early global worldview, one learned not from the pages of geography textbooks, but from the words and images that filled their magazines and from the commodities that littered their homes, farms, and cities. In this book, I explore some of these commercial geography “lessons” in order to understand how American economic dominance throughout large portions of the world came to be understood by everyday Americans as natural, inevitable, and fundamentally good.

Most “metanarratives” of American expansionism point to the 1898 Spanish-American War as a critical starting point — to the rallying cries of Teddy Roosevelt up San Juan Hill and the acquisition or annexation of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Guam, and Hawaii.1 Yet long before military men and machines had reached the shores of other nations, American products — not American guns — were busy “subduing” and “civilizing” the “natives.” Since the mid-19th century, the United States had been engaged in what has been called informal imperialism, defined by Mark Crinson as a “form of imperialism by which control was established through ostensibly peaceful means of free trade and economic integration.”2 The ideological configuration of this era of imperialism informed both America’s military interventions of the late 19th century and its later economic and cultural dominance over large portions of the world. Central to this configuration was the belief that American economic expansion beyond its national borders was different from, and better than, the military and political maneuvers of imperial Europe. In other words, American commercial expansion was, as the opening quote of this chapter suggests, a great work of peace, a noble cause.

Figure 1.1 Cover of 1894 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal, with the following mailing label: Mrs. Helen A. Chase, 4 Maple Ave., Haverhill, MA. (Collection of the author.)

Today, most people would have difficulty taking the sentiments behind this idea seriously. Judging leadership in the world by the “successful development of the great works of peace” would require attention to international aid agencies, health care initiatives, or the number of political and cultural ambassadors. In 1875, however, a very different meaning was at hand: “great works of peace” referred to machines and other industrial commodities, not medical breakthroughs or international governing bodies. This quote was taken from a book published in anticipation of America’s Centennial Exhibition, held in Philadelphia in 1876. What was on display there were the products of industrial development — machines and the commodities they made. How and why these things were represented as “works of peace” by companies that sold them overseas, and in what ways this discursive fashioning of commodities as “gifts” constituted and reshaped Americans’ understanding of other peoples and cultures, is the subject of this book.

What I examine here are the ways in which America’s first international companies positioned their actions — selling commodities overseas to increase revenues — as part of the civilizing process (that is, as a way of sharing the benefits of industrial development with others) and how, in turn, this positioning created different meanings of and knowledges about other peoples, nations, cultures, and places. I focus on the cultures of business, using businessmen and women (managers, advertisers, corporate presidents, salesmen) as the “cultural mediators” whose images and texts were constituted from, and in turn contributed to, one of the major narratives of American expansionism. The story of American expansionism, as the first quote at the beginning of this chapter suggests, starts with the notion of American exceptionalism based on a moral and political superiority over Europe. However, these commercial “cultural mediators” add to this story in two ways: first, they imply that American superiority is a fact that is reflected in and can be judged by the quality and quantity of its manufactures, not in its colonial conquests; second, they add a dynamic and fluid quality to this equation of commodities and morality, such that industrial commodities are seen to lead to “peace” in other places over time.

This is a book, then, about the United States and its business cultures; it does not directly address the impact of American goods on, and the narratives they brought with them to, other places. I interpret the cultural representations produced by five of the largest American international companies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries — Singer Manufacturing Company3 (and its various subsidiaries), McCormick Harvesting Machine Company (International Harvester after 1902), H.J. Heinz Company, Eastman Kodak Company, and the New York Life Insurance Company (though I focus on the first three) — in relationship to the particular international experiences and cultures of these companies and the larger socioeconomic context and ideological formations of turn-of-the-century America. By so doing, I add another, and at times different, layer to our understanding of imperialism — that is, to our understanding of how power is imposed on people and places beyond national borders. The companies I examine produced visual and verbal images of foreign worlds and cultures that made the purchase of American commodities by foreigners appear normal and inevitable, and thus made it seem only natural that the United States would continue to supply the world with its industrial products. Foreign peoples and nations, in other words, were positioned as consumers, as feminized subjects, with the United States positioned as the masculine producer. In this way, the contested and complex story of American economic dominance over large portions of the world came to be seen by many Americans as inevitable and as natural as the patriarchal family. This was accomplished through a reiteration of a particular set of visual and verbal stories about “others” living outside the borders of the United States, stories that emphasized access to commodities as a way of signaling difference, reinforcing contemporary racial thinking that associated whiteness with industrial development.4 Yet the focus on commodities opened the possibility that “others” could in fact become white, with all the attendant anxieties that such a “shock of sameness”5 might produce. As a result, the stories these early American international companies told about “others” were comprised of various strategies to reassert difference, strategies that were often contradictory but nonetheless remained rooted to the expansion of consumption.

This understanding is important to the ongoing critical reassessment of imperialism — what has been called a critical postcolonial perspective — that has been undertaken by geographers, historians, cultural theorists, and others. American imperialism has, until recently, been understood in terms of its territorial and political claims, commencing with the Spanish-American War and continuing with increasing vigor through to the late 20th century as the United States became the dominant global power.6 In this view, the story of American imperialism is a narrative dominated by the movement of troops, capital, and resources. It is about conquest, production, and destruction. Yet, as scholars are now showing, a complementary but different story of imperialism also needs to be told, one that is as much about “civilization” and consumption as it is about conquest and production.7 This form of imperialism was perhaps more subtle than what scholars have examined, but it was no less effective in creating systems of global economic and political dominance. In fact, one could argue that a primary instrument for the spread of American influence in the late 19th and 20th centuries has been the selling of consumer products. It is no coincidence that the so-called “American Century”8 is also what Gary Cross calls “an all-consuming century”9; in other words, the United States’ ascendancy throughout the 20th century into a position of global dominance coincides with, and in fact I will argue is inseparable from, the dominance of an American-style consumer culture and economy over national and international spaces.

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, American foreign and economic policy was geared not toward the establishment of formal colonies but toward the expansion of markets. For the most part, the United States’ political and economic elites were not interested in establishing territorial colonies, nor did they want to be involved in the administration of political subjects. Rather, they sought worldwide markets for American mass-produced goods.10 Why they chose to do so — in other words, why the United States embarked on economic instead of territorial expansion — is a question scholars have long pondered and one that requires close attention to the particular historical and geographical contexts in which American economy, society, and culture were formed.11 The focus on mass production and consumption can be partially explained by the relatively high cost of labor in the United States (leading to the development of a type of capitalism that was reliant on profitability through high levels of productivity and that fostered technological innovations); by the push to take advantage of economies of scale within the expanding and seemingly endless markets of the “frontier”; and by a culture that early on required material acquisition as the determinant of status or class. With an overriding political ethos that favored individual rights as the “key” to democracy, and without the immediate need to engage in European power struggles, the United States’ economic and political elites simply followed a path to economic growth that was well honed from their experiences creating a national market; empire-making in the sense of colonial acquisitions was beside the point. The United States was engaged primarily in informal imperialism, in promoting trade and economic integration that suited the needs of American corporations. American empire, then, was as much about ordinary commercial transactions as it was about political maneuvers or military interventions. Imperialism in this sense was enacted daily — on the docks, in the grocery stores, and at home. Decades before the Spanish-American War, American businesses were developing international marketing strategies, establishing shipping and transport networks, and reaping the rewards of an expanded consumer market. At first, in the 1870s and 1880s, the primary markets for American goods were the countries comprising Western and Eastern Europe (including Russia) and Canada. Later, depending on the particular commodity, other important markets included Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, India, Japan, Turkey, Thailand, China, South Africa, Chile, and Peru.

This is not to deny, however, that the United States also engaged in formal imperialism, sending large armies into Mexico in 1846 and establishing what can only be called “colonies” in Cuba, Guam, Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico through military and political manipulations coincident with the 1898 Spanish-American War. The causal relationships between America’s formal and informal imperialism are complex, to say the least, and not always as one would expect. For example, although most American international companies supported the 1898 war for patriotic reasons (it was an incredibly popular war), many of the major players in America’s boardrooms did not favor any future military incursions, finding that wars and imperial governance got in the way of trade and marketing.12 On the other hand, America’s formal imperialism, particularly in the Philippines, did lead to increased trade and economic integration, but this economic activity was basically inconsequential when compared to America’s primary markets in such places as Russia, Argentina, and Brazil. Compared to the importance of economic integration within the British formal imperial world, United States’ formal empire contributed relatively little to the global reach of American companies.13

That American goods competed successfully even with Britishmade products attests to the formidable strength of American mass production technologies and to the innovative marketing strategies pursued by many entrepreneurs.14 In other words, America’s economic imperialism was based primarily on the making and selling of mass-produced commodities. Scientific innovation combined with Taylorist production facilities allowed American manufacturers to ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- 1. Selling Civilization

- 2. The Geographies of Commercial Empire

- 3. The “Great Civilizer” and Equalizer: Gender, Race and Civilization in Singer Advertising

- 4. Manliness and McCormick: Frontier Narratives in Foreign Lands

- 5. Holidays with Heinz: The Foreign Travels of Purity and Pickles

- 6. Flexible Racism

- Index