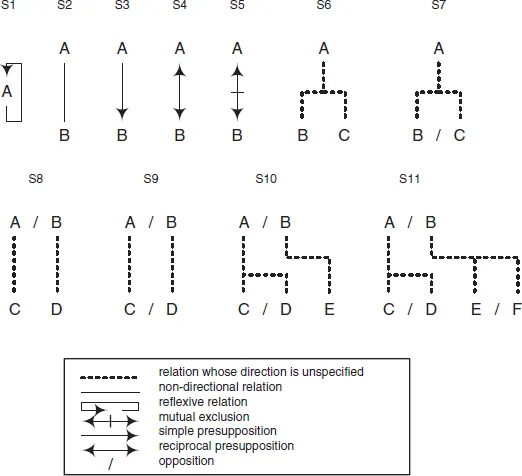

We propose a methodological distinction between four basic kinds of semantic relations: (1) comparative relations: identity, similarity, alterity, opposition, homologation, etc.; (2) temporal relations: simultaneity and succession, etc.; (3) presential relations: simple presupposition, reciprocal presupposition and mutual exclusion; (4) relations of inclusion: set relations (involving classes and/or elements thereof), mereological relations (involving wholes and/or parts), and type-token relations (involving types and/or tokens); and (5) other semantic relations.

Temporal and spatial relations

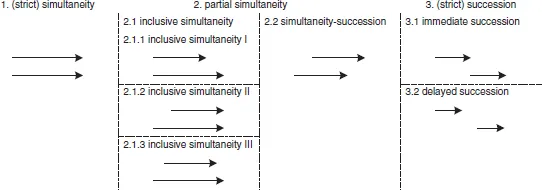

Simultaneity (or concomitance) is the relation between terms associated with the same initial and final temporal positions, and thus with the same temporal extent (duration). We can distinguish between strict simultaneity (1) (as in our definition) and the following kinds of partial simultaneity (2): inclusive simultaneity (2.1) (in which the first time period is entirely contained within the second, and is exceeded by it); inclusive simultaneity in which the initial positions coincide (2.1.1); inclusive simultaneity in which the final positions coincide (2.1.2); inclusive simultaneity in which the initial and final positions do not coincide (2.1.3); simultaneity-succession (2.2) (partial simultaneity and succession).

Succession (3) is the relation between terms in which the final temporal position of one term precedes the initial position of the other term. Immediate succession (3.1) implies that the initial position of the second term comes immediately after the final position of the first term; otherwise we have mediate or delayed succession (3.2). A distinction can be made between strict succession (3) (addressed in the preceding definitions) and simultaneity-succession (2.2), a form of partial simultaneity and succession.

The following diagram illustrates the main dyadic temporal relations.

These temporal relations have spatial correspondents, and thus, through generalization, they are relations of extent, whether the extent is spatial or temporal; but other spatial relations exist as well.

Figure 1.2 Dyadic temporal relations

Presential relations

A presential relation is a relation in which the presence or absence of one term indicates the presence or absence of another term.

Presupposition is a relation in which the presence of one term (the presupposing term) indicates the presence of another term (the presupposed term). This type of relation can be described as “both … and …” (both one term and the other term). Simple presupposition (or unilateral dependence) is a unidirectional relation (A presupposes B, but not the reverse). For example, the presence of a wolf presupposes the presence of a mammal (since the wolf is a mammal), but the presence of a mammal does not presuppose the presence of a wolf (since the mammal could be a dog, for instance). Reciprocal presupposition (or interdependence) is a bidirectional relation (A presupposes B and B presupposes A. For example, the back side of a sheet of paper presupposes the front, and vice versa; in fact, there is no front without a back, and vice versa. We can represent simple presupposition by an arrow (A presupposes B would be written as: A → B, or B ← A) and reciprocal presupposition by an arrow with two heads (A ↔ B).

Mutual exclusion is the relation between two elements that cannot be present together. This type of relation can be described as “either … or …” (either one term or the other term). For example, in reality, a single element cannot be alive and dead at the same time (which does not necessarily apply in a semiotic act, such as a fantasy story).3 We can represent mutual exclusion by using two arrows pointing toward each other (A →← B) or a vertical line (A | B).

If the presence of the terms is viewed not from a categorial standpoint (of all or nothing), but from a gradual (and thus quantitative) standpoint, two types of correlation may then be found between two terms. The correlation is said to be direct if (1) an increase in A leads to an increase in B and vice versa, and (2) a decrease in A leads to a decrease in B and vice versa. A direct correlation, thus, is a “more … more …” or “less … less …” type of correlation. For example, when the kinetic energy of a car increases, its speed also increases, and if its speed increases, its kinetic energy does, too.

The correlation is said to be inverse if (1) an increase in A leads to a decrease in B, and an increase in B leads to a decrease in A, and (2) a decrease in A leads to an increase in B and a decrease in B leads to an increase in A. An inverse correlation, thus, is a “more … less …” or “less … more …” type of correlation. For a constant quantity of gas at a constant temperature, pressure and volume are inversely correlated; i.e., if the volume is increased, the pressure decreases, and if the pressure increases, it is because the volume has decreased.

Direct and inverse correlation can be compared to reciprocal presupposition and mutual exclusion, respectively. That is, in a direct correlation, by raising the degree of presence of one term, I increase the presence of another;4 in an inverse correlation, by raising the degree of presence of one term, I decrease the presence of another (or in other words, I increase its degree of absence). For more details, see the chapter on the tensive model.

A presential relation is not necessarily coupled with any relation, i.e., joining a cause to an effect, or a non-effect to a cause or the absence of a cause. The following is a presential relation not coupled with a causal relation: A few decades ago (perhaps it’s still true), if you changed your altitude, you also changed your chances of dying of a lung disease; to be precise, the two variables were directly related. It would be wrong to think that altitude was harmful to the lungs; it was just that those who were seriously ill were advised to live in the mountains. The following is a presenti...