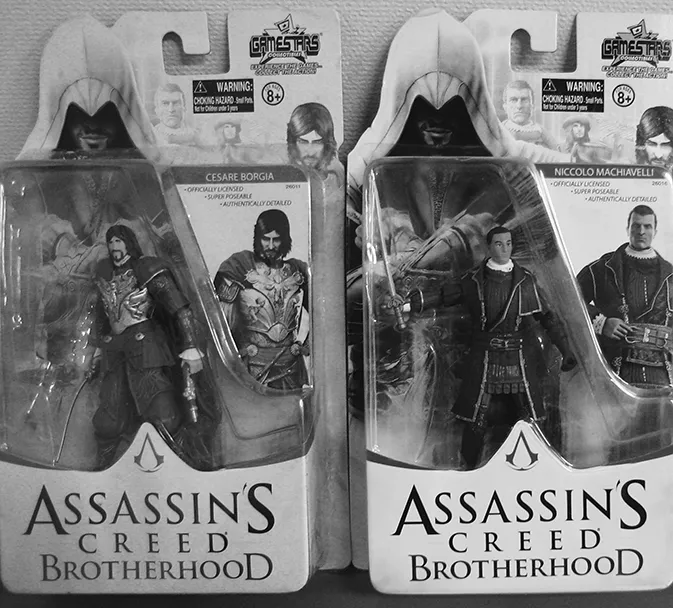

powerful leaders who seem a lot like us, only better, also worse – people of wealth, sophistication and wit who, on occasion, resorted to methods that ordinary people sometimes fantasize about but don’t dare try. They have come to symbolize opposite things, of course.1

Stanley tells her readers that “despite waves of revisionism and reappraisal,” the Kennedy family still represents the United States at the peak of its influence and post-World War II global power. In contrast, the Borgia family “represent[s] a low point in the Renaissance Church when corruption and greed defined the papacy.”2 As symbols, these two families have been surprisingly resistant to change. Yet unlike The Kennedys, which was dropped by the History Channel following a campaign of complaints and criticism from “Kennedy family friends and friendly historians,” the Borgia family and its television series have attracted few historians who are willing to identify rumor and malicious or ill-informed representation as being the bulk of the family’s historical reputation.3

The difficulty lies in how the creators of these reincarnations craft their narratives and characters. In describing how he approached playing Alexander for Jordan’s series, Jeremy Irons described making a list of his qualities:

The list goes all the way from ‘generous man,’ ‘wonderful company,’ ‘a great organizer’ to ‘poisoner,’ ‘cruel’ and ‘despotic,’ all the worst adjectives you can think of … But] I never judge. That’s not my job. I just try to link all those attributes.6

Intentional judge or not, the very fact that Jordan and Irons present Pope Alexander VI to the public as both a generous man and a poisoner is a judgment on the soundness of the existing historical narratives. Few television writers or reviewers discuss the usefulness of historical sources, but this is exactly the current situation demanded of popular writers about the Borgia family.7 Their historical reputation is built out of conveniently damning accounts, often invoked with little to no corroboration, or from a chronological distance and a clear political opposition. As this volume shows, these accounts have been repeated for centuries, with few “friendly historians” digging deeper into the past to clear away the dirt of reputation and dispel or contextualize the accumulated Black Legend.8 While Michael Mallett’s foundational study The Borgias: The Rise and Fall of a Renaissance Dynasty has made the greatest contribution to this effort, the anti-Catholic, anti-Spanish narrative has had five centuries to settle in and attract millions of voyeuristic enthusiasts.9 The expansion of entertainment media has allowed the proliferation of variant histories that mix and match events and characterizations to create entirely new presentations of the past. Modern historians can be forgiven if they are torn in two directions. Who does not want the reading and watching public to be more aware of and interested in one’s research subject? Yet, enthusiasm for many of the modern Borgia productions implicitly equals acceptance of narratives of corruption, murder, and incest. This black and white world, of good and bad, of acceptance and opposition, of modern and early modern depictions, ignores the historical reality that is built out of a thousand shades of gray and continues to evolve via reincarnations.

The purpose of this collection is to explore the continuing depiction of the Borgia family across the five centuries since Rodrigo Borgia was elected pope. The historians, art historians, and theatre historians who have contributed to this volume explore the family through both archival and secondary sources, but are not unaware of how the Protestant Reformation, the democratic nation state, and modern television audiences have affected its public appearance. By analyzing aspects of the narrative, participants in the historicized events, and trends in depictions, a deeper understanding of the family and its audiences appears. Moreover, the entangled relationship between the past and popular culture emerges, showing just how cannibalistic entertainment remains. There is little doubt that the Borgia family, resident in the Vatican Palace and wed to European royalty, bears little relationship to most of its readers and viewers. If it did “seem a lot like us,” to use Alessandra Stanley’s words, we would likely not be interested.10 Rather, audiences enjoy the thrill of elite debauchery, made even more titillating by the ecclesiastical environment, and its safe distance centuries past in a supposedly unreformed world. This introductory chapter lays the groundwork for the studies that come after it, all of which draw on ideas of rumor, reputation, representation, or recreation. The rumors that built the Borgia family’s reputation “of scheming, bribing, and poisoning their way to the top” are followed and disassembled in order to show their influence on later creators and the reinvigoration of modern productions.11 In effect, by bringing the past and the present together, we explore how historians and artists have combined rumor and reputation to create the family’s many representations and explore their current meanings.

Understanding the past, weighing the evidence

The idea and opportunity for this collection came to life in a period of preoccupation with undergraduate teaching, and specifically designing (and redesigning) a new historical methods course. While the Borgia family may not initially appear relevant to the extended discussions of teaching narratives, student learning outcomes, competencies, and assessment rubrics, it has come to embody one of the central challenges of teaching history in the twenty-first century. Evidence, narrative, bias, and audience are at the heart of (mis)understanding the Borgia family. Indeed, understanding the family is more about perceiving the development of its historical reputation, built successively on action, rumor, and eventually representation. Historians are both to blame and able to contextualize the Borgia family within its current situation. In this fashion, it is a lot like a historical methods course: identify the historian, highlight the argument, evaluate the evidence, and corroborate the message and its purpose.

In many ways, this topic’s specific challenges also reflect the undergraduate student’s own struggle to do these very things. The tension between teaching about the past and teaching what the historian does can be overwhelming. How does a student learn to detect the historian’s voice if only content is privileged on tests or in films? How does the historian convince students of the value of historical thinking skills when content is everywhere and the plot is far more interesting than the discipline’s contested interpretations? Why consider the construction of typologies, limited agency, or evidentiary holes when a denominational mindset is so easy to adopt and a reformer’s indignation is so much fun to wield? Would it not just be more enjoyable to relate scandalous stories about popes with kids and ignore present-mindedness? Yes, but only if the goal is an acceptance of all narratives as truth and the dismissal of evidence-based analysis.

Many historians and educational psychologists have argued that now more than ever it is essential for all people to be able to evaluate narratives and the analysis from which they emerge in order to discover and weigh both evidence and the author’s positionality.12 Paradoxically, as sources of information multiply, popular narratives repeat, and the Internet allows greater global access, many people have narrowed the spectrum of opinions that they encounter.13 In a world of polarized viewpoints the analytical skills that are the foundation of the Humanities must be employed with increasing frequency. This is as important for exploring the early modern papacy as it is for modern politics. Regardless of which end of the opinion spectrum one gravitates towards, we all want to know where our information comes from and who is telling us what to believe.

As Jerome de Groot has argued, “television and visual versioning of the past is increasingly influential in a packaging of historical fact and a creation of history as leisure activity.”14 With a long history on page, stage, and screen, the Borgia family is now at the center of “visual versioning” for the living room or mobile device; a trend that previously was limited to monarchs and presidents. This is not the production of documentaries, with historians in period buildings commenting on motive and evidence, but historical narratives that visualize a life or event, bounded by beginnings and endings, and presented as a plot driven by personalities. The Borgia family has joined the ranks of The Tudors (Showtime, 2007–2010), another recently re-envisioned family, which belongs to a genre of historical television series whose main attraction has been described as “a costume-drama sexual hopscotch.”15 In fact, this characterization is nothing new; merely a return to the spotlight and a larger audience for a family that has been the focus of writers and artists for centuries. Without overstating the facts, the theme of multiple sexual partners runs throughout the Borgia family; firstly, for Rodrigo Borgia’s mistresses, and secondly, his daughter Lucrezia Borgia’s husbands and fathers of her children. From this perspective the Borgia family is perfect for the current sexually explicit and adventurous character of big-budget cable television.16

However, as a narrative, the Borgia family suffers from a similar fate as the Tudor dynasty. Tatiana String and Marcus Graham Bull have explored the fragmentary effects of the Tudor dynasty’...