This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Mughal Warfare offers a much-needed new survey of the military history of Mughal India during the age of imperial splendour from 1500 to 1700. Jos Gommans looks at warfare as an integrated aspect of pre-colonial Indian society.Based on a vast range of primary sources from Europe and India, this thorough study explores the wider geo-political, cultu

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Mughal Warfare by J.J.L. Gommans in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia del mundo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Indian frontier1

India abounds with forests and extensive wildernesses, full of all sorts of trees; so much so, that these wastes seem to offer inducements, both to rajas and subjects, to revolt from the government. The agricultural population, and the abundance of cattle, in this country, exceed that of all others; but its depopulation and desolation are sudden and rapid beyond conception.

(Firishta)2

The history of warfare cannot do without geography. Therefore, this chapter pays tribute to the geographic dimension of history as suggested by those almost forgotten early geographers like Alexander von Humboldt and Carl Ritter. Decades before the emergence of the famous French Annales school, they aimed to investigate the ways in which the physical environment affected human societies. In our case, we will examine to what extent the military campaigns of the Mughal emperors were ruled by the long–term geo–political imperatives of the Indian sub–continent. First, we will find that India’s well–known monsoon winds created, in fact, two entirely different ecological zones: open drylands in the west, and dense humid forests and marshes in the east. As a result, India emerges as an extensive transitionary area between the so–called Arid Zone dominating West and Central Asia, and Monsoon Asia covering East and Southeast Asia.3 Here, it will be highlighted that these zones were governed by entirely different conditions for agricultural and pastoral production that determined the availability of military recruits and of crucial instruments of war, such as elephants and warhorses as well as of food and fodder. Despite the image of a civilisation despising violence and reserving it for certain martial castes, during Mughal times India experienced a remarkably high degree of military participation from almost all sections of its population. Indeed, the social distinctions appeared to be less important than the ecological circumstances that gave India’s drylands, both in terms of man– and horsepower, by far the largest military potential. On the other hand, Indian armies also needed the rich supplies of India’s agrarian centres, either in its more humid parts or well watered by its various river valleys. Hence, the Mughal Empire tended to gravitate towards an ever–open inner frontier between settled agriculture and arid marchland, whereas the dense and humid forests and marshes of northern and eastern India were clearly part of its more natural, outer frontier.

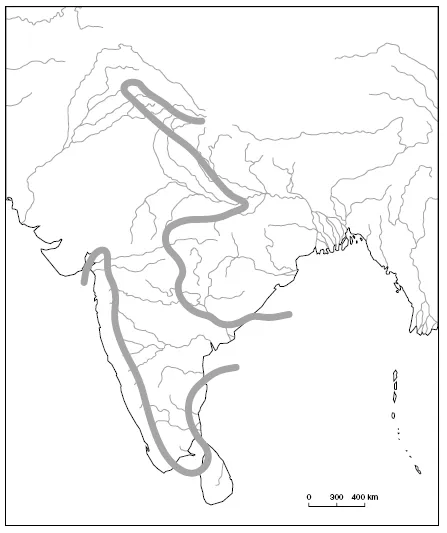

Further elaborating on the frontier theme, the second section will stress the pattern of India’s network of long–distance routes. As in the case of the Roman Empire, in principle these Indian limites were unbounded and, as such, dictated the direction of unrestricted expansion.4 Indeed, as a kind of saddle state, the survival of the Mughals hinged on the combined control of both the areal inner frontiers and the linear limites of empire. Interestingly, both converged most ideally in those areas that, throughout India’s history, developed as more or less perennial nuclear zones or bases of political power; in other words, those regions that combined a rich agrarian base with extensive pasturage and important long–distance commercial connections.5

Monsoon and Arid India6

In broad ecological terms, the monsoon winds give some kind of uniformity to India as a whole. But, even in ecological terms, this apparent uniformity again turns out to be no more than another version of India’s well–known unity in diversity motto. In its most general terms, the monsoon winds deliver a climate in which a cool, dry season of northerly winds, i.e. the northeast monsoon from December to February, gives way to a hot, dry season from March to early June, followed by a hot, wet season of southwesterly winds, i.e. the southwest monsoon from July to September, then a return to the dry, cool season of the winter months. As early as June the monsoon has an effect at the southwest coast, thanks to the high Western Ghats. Somewhat later, in July, the monsoon hits Bengal, after which it gradually spreads towards the northwest with rainfall decreasing and becoming less reliable. India’s double agricultural season neatly follows this annual rhythm of the monsoon. Especially, the so–called kharif harvests profit from the monsoon torrents. Here, sowing begins after the first onset of rain, while harvesting takes place in about September or October. In some cases, the harvests occur much later, depending on the crops and the long–term availability of water through irrigation. The winter, or rabi, crops need less water but cannot stand the heat of summer. They are sown soon after the rains – that is, almost simultaneous with the kharif harvest – and are usually taken in during spring. In the drier regions, rabi crops are important in areas under irrigation or with some precipitation during winter, such as along the southeast coast following the northeast monsoon or, to a lesser extent, in the Punjab as a result of the depression rains during the winter months.

Despite these unifying characteristics of the monsoon, in practical terms it is more fitting to emphasize an east–west dichotomy in India’s monsoon climate, in which the eastern parts are more humid with higher and more reliable agricultural yields, primarily through transplanting cuttings and seedlings of rice, whereas the western parts are more arid with lower and less certain harvests, mainly through direct seeding of millet and wheat, and mostly depending on irrigation by rivers, canals, tanks or wells. In the latter case, an exception should be made for the very humid southwest coast of Malabar and the Konkan as well as for the marshy Terai of the Himalayan foothills. The critical difference between the two zones is the supply of water. This depends on both the amount of rainfall and its distribution throughout the year, all in combination with factors that determine the length of the growing period of plants, such as soil storage and evaporation. Geographers generally refer to India’s dry lands as having a growing period of less than 180 days that corresponds roughly, of course hinging on the regional circumstances, with 1,000 mm of annual rainfall.7

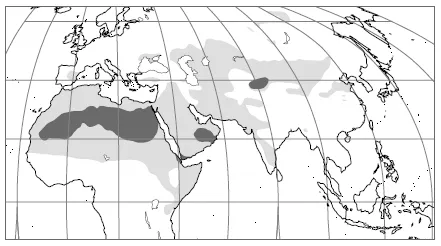

As mentioned already in the Introduction, these drylands are part of that much wider, frequently broken, ecological continuum of the Arid Zone – sometimes called Saharasia – that includes all the drier zones of Eurasia, stretching from the Atlantic coast of northern Africa to the eastern and southern extremes of the Indian sub–continent.

To be somewhat more specific, in India it extends from the very dry tracts of Sind and Rajasthan, branching off in eastern and southern directions. Going eastward, while embracing the large medieval capitals of Lahore, Delhi and Agra, it follows the courses of the Yamuna and Ganges rivers and, subsequently, narrows down along the southern banks of the Ganges until it reaches, at the head of the Ganges delta, the fertile and more humid paddy tracts of eastern Bengal. Going southward, it stretches from the extremely arid Thar Desert across the Aravalli Mountains into Malwa. Behind the dry lee side of the Western Ghats, it continues towards the dry western Deccan plateau. The eastern slopes of the mountains or Mavals still receive substantial amounts of rainfall and, as such, serve as a transitional zone between the humid littoral – its 4,500 mm permitting intensive rice cultivation – and the dry interior of the desh – its less than 500 mm making this the natural habitat of pastoral groups. The high aridity of this area continues in a southeastern direction into the Raichur doab between the rivers Tungabhadra and Krishna and extends towards the so called Rayalaseema, literally ‘the frontier of the kingdom’, around Kurnool and Cudappah in the south. This became a hotly contested border region between the prevalent powers in the Deccan to its north and the Carnatic to its south. South and east of the Rayalaseema, rainfall increases again, partly profiting from the northeast monsoon, but usually stays well under 1,000 mm. In the southwest, the Mysore Plateau, with rainfall of between 600 and 900 mm, still belongs to the Arid Zone and, from there, several dry outliers reach the extreme southern end of the sub–continent. In the southeast, the Arid Zone descends the relatively gentle slopes of the Eastern Ghats towards the more humid Coromandel Coast. Although rainfall is far from excessive, its numerous wide river deltas have made this one other core area of intensive rice cultivation. As such, the Arid Zone serves well as a kind of central dry axis connecting the three ancient centres of sedentary civilisation emerging along the Indus valley in the west, along the Ganges and Yamuna valleys in the north, and along the river valleys of southeastern Cholamandalam.

Map 1.2 Saharasia

Although in terms of rainfall these ancient centres of civilization are part of the Arid Zone, India’s life–giving rivers have made these alluvial lowlands fertile and well irrigated. Hence, the Arid Zone consists of major, for the most part alluvial, agricultural areas intersected with arid march lands where agriculture is far less stable.

In most of the Arid Zone, millet and wheat dominate the production throughout the agrarian year. Compared with rice, these require less intensive labour but, at the same time, produce lesser and more unreliable harvests. Although India distinguishes between at least two agricultural seasons, most areas concentrate on one harvest only, while in the other season fields are left fallow for longer periods. More complex forms of rotation are also common, as well as the risk–avoiding custom of sowing two different crops simultaneously in the same field, such as wheat with cotton. Not surprisingly, the drier parts of the Arid Zone are often equated with a famine tract, in which the inhabitants always had to resort to wide ranging survival strategies in case of failing monsoons. In some areas, they sought additional livelihoods like cattle tending, spinning or weaving, or peddling. But, as pointed out by Dirk Kolff, many of these peasants looked for temporary employment at the mostly booming military labour market of Hindustan.8 Many peasants offered their services at the end of the agrarian season in October, either after kharif harvesting or rabi sowing. Indeed, the existence of a most extensive military labour market supplying tens of thousands of armed peasant–soldiers each year is one of the most salient features of military life in northern India and should be closely linked to the specific conditions of India’s drylands. Hence, October not only marked the start of the peasant’s off season but also the beginning of the war season – setting out for campaigns of plunder and conquest. In classical Indian texts it finds expression, for example, in the timing of the ancient horse sacrifice, when the sacrificer–king sent out a whole army to follow and protect the horse that, later, on its return from the campaign, would be immolated. Its armed retinue was licensed to plunder those who would oppose the horse’s triumphant progress. Later on, we find similar examples of this kind of military parody, such as in the annual nine–day Dashahara or Mahanavami festival, in which the king’s military potential was displayed and reviewed in exuberant processions. Indeed, after the retreat of the monsoon, as roads became more accessible and pastures were at their most luxurious, raiding always provided a tempting option to tide over the long agrarian off season.9

Map 1.3 Arid India

All this does not mean, however, that all arid regions were equally sensitive to such risk–avoiding considerations. On the fertile black soils of the northern Deccan, for example, cotton was cultivated and processed, which required an almost year round labour input. Besides, apart from plundering or more regular military labour, there could be many other alternatives for employment during the off season, such as trading or, as we shall see, cattle–tending. But, more generally speaking, with the combination of unreliable harvest and a long off season, the peasant population of the Arid Zone appears to have been more liable to the attractions of military service than that of Monsoon Asia. In areas with heavy rainfall, such as Bengal or Kerala, but also in those areas that were more permanently irrigated, it was easily possible to alternate kharif and rabi crops on the same fields every other year. In some areas, which were dominated by paddy cultivation, there were even three annual crops that kept peasants busy all year round, producing heavy yields per acre. Of course, all this does not imply that the paddy fields of eastern India did not produce military labour. The crucial point is that the organization of military labour tended to be different in both zones. In the dry lands, military labour tended to be part–time, seasonal and thus less specialized. The arid tracts were the ideal recruiting ground for irregulars, as easily gathered as dissolved at the end of the campaign. By contrast, in areas in which peasants did not have a long off season, military labour tended to be full–time and more professionalized. Such more regular armies required, however, long–term financial investments. This appears to have been exactly the policy of the East India Company, which recruited its well–drilled infantry sepoys mainly from the fertile eastern tracts of Hindustan. The same goes, probably, for the reputedly well–trained infantry units of the Nayars in Kerala or the Ahoms in Assam. By contrast, the Mughals took the bulk of their army from those more arid parts that Stewart Gordon recently designated as India’s three major military recruitment zones: the Rajput zone in the northwest, the Maratha zone in the eastern Deccan and the Nayaka zone in the southern Carnatic.10

Not surprisingly, perhaps, the basic physiological divide between Arid and Monsoon Asia can also be traced in the old Sanskrit texts dealing with Ayurvedic medicine. As analysed by Francis Zimmermann, these highly idealised and normative treatises also draw a clear–cut distinction between the marshy anupa lands of the east and the dry jangala lands of the west. Anupa represents all the places where water abounds, not just marshes, but also rain forests and liana forests and mangroves, with all kinds of unhealthy connotations of fevers and parasites. The opposite is the jangala – clearly distinct from the present–day meaning of the word – defined by the scarcity of water, and mostly consisting of wild, open savannahs. In modern–day medicine, its Ayurvedic divide reappears in the distinction between the eastern areas where malaria is endemic and those western areas where it is epidemic. What is most interesting to the military historian, however, is that these idealised texts seem to confirm the ecological division of military labour. For example, they distinguish between two different types of human species: the eastern ones being fat, rotund and susceptible to disorders of the phlegm, the western ones being thin, dry and of a bilious temperament. One also finds other instances in which the vegetarian India is contrasted with the warlike regions of the north and northwest, with their eaters of meat and drinkers of alcohol.11 Chris Bayly gives other examples of this traditional strand of anthropogeography that links climates and products of places to certain characteristics of its inhabitants. Hence, the martial Marathas become depicted as dry and hot because their diet consists of pulses, oils and chillies.12 In a way these associations seem not that much different from the later, racist descriptions of British surveyors selecting the so–called martial tribes of India. Far from being natural phenomena, however, these normative portrayals partly appear to reflect real ecological and agricultural circumstances of the Arid Zone, which made military employment a viable and – as we shall see in the next chapter – attractive option in the survival strategy of both peasants and landlords.

The distinction between Arid and Monsoon India based on the agricultural regime corresponds neatly with that of pastoral production: pigs, buffaloes and ducks in the east; horses, camels, cows, sheep and goats in the west.13 In the east, there is almost no room for extensive nomadic pastoralism since the jungles contain dense tropical rain forests or swamps, whereas the arable land consists of permanently worked paddy fields. Although there exist a few transhumant pastoralists tending larger herds of buffaloes or bullocks, the range of their movements is confined to a relatively limited area, as, for example, those transhumant herding communities travelling up and down the Himalayas. Most of the inhabitants of the monsoon forests combine some form of shifting cultivation with hunting or gathering. In military terms, they are not in a position to prevail over the peasants of the more settled society. Not surprisingly, the forest tribes often served as slaves, either used in the local households or exchanged in the long–distance trade. Apart from the famous Himalayan slave trade, the market in eunuchs from Assam and Bengal provides a well–known example. We should not forget, though, that these same forests contained one of the most important instruments of war in India: the elephant. To the forest dwellers the animal hardly rendered any military might since elephants were fit for neither breeding nor tending by pastoralists. In fact, at the age that they became useful for military or other purposes, they were caught by large–scale hunting expeditions. For the Mughals, this royal prerogative was the main attraction that drew them towards the unhealthy, malaria–infested forest fringes of the Himalayas, Assam, Bengal and Orissa.

The wild jungles of the dry lands stand in sharp contrast to this. These jungles mostly consisted of open savannahs providing extensive pasture for large herds of camels, horses, bullocks, goats or sheep. Apart from sheer space, its nutritious natural grasses and fodder crops made the Arid Zone more suitable for stock–breeding. Apart from its grasses and forest scrub, cottonseed or the stalk and leaf of dry millet, two of the major dry crops, served as excellent supplementary fodder. In Chapter 4 I will point out the link between arid grasses and the breeding quality of warhorses. Although the best warhorses came from West and Central Asia, India’s drylands could produce excellent horses, in particular when provided with streams as well as with good long–distance connections to the major breeding centres of the northwest. Hence, the dry valleys of the Sutlej and Bhima rivers grew into healthy breeding grounds for horses. For the present argument, it will suffice to conclude that, for the supply of their warhorses, the Mughals crucially depended on the pastoral economy of the Arid Zone. In addition, the same dry marches not only produced horses but also excellent breeds of dromedaries, which, like horses and elephants, were used as military instruments but which, more significantly, also served extremely well as beasts of burden. Because the radius of action of the dromed...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Abbreviations

- Note on Transliteration

- Introduction

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Conclusion and Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography