This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Intelligent Buildings in South East Asia

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The growing demand for high quality office and manufacturing space in South East Asia has led to an increasing awareness of 'intelligent building' concepts. This study is based on a major research project undertaken by three leading players in the construction industry - DEGW, Northcroft and Ove Arup & Partners - which looked at user requirements and changing patterns in the workplace. The book also contains key findings from the earlier Intelligent Buildings in Europe study undertaken by DEGW and Tecknibank and provides in one volume essential information on building intelligence.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Intelligent Buildings in South East Asia by Andrew Harrison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Intelligence in Buildings

1 Organizations

2 Information Technology

3 Facilities Management

1 ORGANIZATIONS

INTRODUCTION

The phrase ‘intelligent building’ can conjure up images of futuristic, high-technology buildings, filled with computer systems and high-technology devices, in which the work is undertaken by the building systems and the occupants are almost superfluous. The building systems are, of course, important — but they are at the service of the organization: a means of meeting business objectives rather than an end in themselves. By providing the appropriate synergy between people, place and IT, the most successful intelligent buildings are likely to be almost invisible. The people working within them will have the appropriate physical and technological supports to conduct their business requirements unaware of the building design and sophistication of the computer systems that may be operating around them.

The intelligent building may in fact be understood as a seamless part of the intelligent infrastructure that serves effective organizational performance. Intelligent building and systems products will have to be highly responsive and adaptive to particular organizational characteristics.

The objective of this chapter is to define the critical organizational issues that should be addressed when designing intelligent buildings and the impact they will have on the office of the future. Through an analysis of the trends in management theory and information technology in the last 20 – 30 years it focuses on the requirements of the organization using the building and defines the relationship between people, places of work and information technology.

Management Theories

Henry Ford's early car factories were innovative in breaking down work tasks into detailed hierarchies of time and motion. An extensive division of labour developed that caused the ‘de-skilling’ of workers’ tasks and the centralization of managerial knowledge and expertise away from the point of production. Management, planning, control and execution became separate functions and tasks undertaken by distinct groups of staff. The scientific management of Taylor and others became the hallmark of mass production and dominated organizations through the first half of the century.1

This began to be challenged in various ways after the Second World War. Particular economic shocks have been identified as the catalysts for organizational change away from the Fordist model. The oil crisis of 1973 and the subsequent crises of inflation and recession are often seen as a turning point. In the UK the deep manufacturing recession entailed by the Thatcher ‘revolution’ in the early 1980s also prompted a major round of restructuring. On a global scale, the rising impact of international competition has forced many organizations to continually re-evaluate their ways of working, resulting in constant change and re-focusing of both organizational structures and goals.

Some analysts described the emergence of post-Fordism as a new economic regime of ‘flexible accumulation’ that emerged out of the end of the long post-war boom.2 If the typical characteristic of Fordism was the mass production of standardized products, post-Fordism is characterized by:

- flexible labour processes

- increasingly automated production systems

- heightened geographic mobility of economic activity

- rapid changes in patterns of consumption

- revival of entrepreneurial activity

- privatization, deregulation and reduction of state economic activity.

Freed of the rigidity of Fordist organizations, many new ways of organizing work have emerged. They have occurred in new sectors of production, including the high-technology sectors (especially electronics) and also in the revived craft and design sectors (furniture, fashion, textiles) and in the many financial and consulting service organizations that blossomed in the 1980s. Many post-Fordist organizations have been innovators in the use of information technology. The electronics sector itself pioneered the technology of calculating, communicating, controlling and processing of data that has supported the typical restructuring of post-Fordist organizations.3

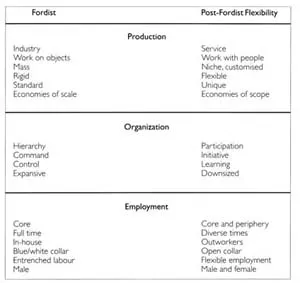

Figure 1.1: Typical differences between Fordist and post-Fordist organizations in terms of production, organization and employment

High volume mass production has changed to specialized flexible production systems. Market niches can be targeted more easily. Products and services can be more finely tuned to consumers’ needs. Forecasting demand and controlling stock becomes easier.

For some, post-Fordism represents a ‘second industrial divide’ with new forms of labour, organizations and locations of work.4 For others, post-Fordism represents the development of market economies in ways that re-use pre-capitalist and domestic styles of enterprise in new ways: outworking, piece work, artisan, domestic and familial organizations and other informal working arrangements. Others see post-Fordism as a dynamic amalgamation of all of these tendencies, the combination of new and old elements affecting both older Fordist organizations and the characteristics of new organizations (Figure 1.1).

Impact of Information Technology

Levels of hierarchy are ineffective in organizations that need to continually readjust their work to suit many different kinds of projects. Such organizations depend on rapidly shifting project teams and a high level of lateral communications.5 The post-Fordist organization is likely to have fewer levels of management which depend on more dispersed information. The flatter organizational profile encourages a more widespread distribution of knowledge and skills.6,7,8

The command-and-control organization typical of Fordism is being replaced by organizations of knowledge experts.9 Knowledge experts use IT to gather and analyse information; create and evaluate ideas; and make decisions for actions. They are workers who discipline their own performance through continuous feedback.

Basic developments that revolutionized computing and telecommunications hardware have provided increasing support to the changes in organizations and business activity. Immense increases in software power and speed and in the development of network systems have all facilitated organizational transformation.

Multi-functional groups, teams, and task-forces can make use of information resources across organizations. IT can support new kinds of decentralization to promote flexibility. Large organizations can be run like small ones.

IT is enabling:

- networks to exchange data and information

- added value services linking companies or parts of companies.

Businesses have gained great advantages in timing, consistency, and accessibility of data and knowledge. Information has become more easily adaptable to changes in strategy and organization.10 The abundance of information creates immense opportunities and risks. The simultaneous power of centralization and decentralization offers great benefits if handled effectively. The mediation between customer and supplier is disappearing. At the same time the organization can operate more tightly and be more responsive. Information systems may become the heart and stable centre of organizations, maintaining history, experience and expertise.11

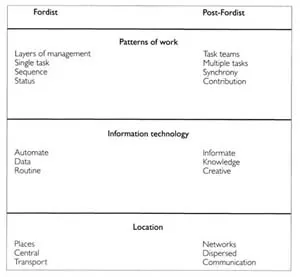

IT allows a greater degree of unpredictability, spontaneity and exceptionality to enter the work process. The work of the office is less about the routine (which can more often be automated) and more about the exceptional. The work process for the individual can be enlarged in scope and intensified.12 But the successful integration of information technology in the organization demands a high level of training to maximize the benefits of the technology for the users. The greatest potential of information technology for the organization will be realized when computers and all IT devices are ubiquitous. Information technology may then become an integral, and therefore ‘invisible’ aspect of the working life of the organization.13 This suggests that these technologies will have achieved their full power when they are incidental aspects of the working process, as much taken for granted as pens and paper were earlier this century. For this to be a reality the relationship between the human quality of life and the use of technologies must be a priority for development. The trends of development towards ubiquitous technologies and IT tools suggest a much closer relationship between the information technology used in the work process by the organization and the technologies of intelligence in buildings. The IT used in the work process is likely to move in the direction of becoming more ‘knowledgeable’ about their location and surroundings, to have the capacity to adapt their response to suit patterns of use and their environment, and to be more adaptable to particular tasks.15 IT may become part of a ubiquitous network, in use as part of every work process (Figure 1.2).

Changing Patterns of Work

When information is used less for the purposes of control and more to support the creation of specialized knowledge, patterns of work are changed.16 Workers in the knowledge-based firms are specialist problem solvers and have to be more highly skilled and better trained. They tend to work in teams and groups, in contrast to the de-skilled performance of standardized individual tasks characteristic of the Fordist organization.

Work may be done by task-oriented teams from various departments supported by distributed information systems. Groups may form and disband to solve particular problems. Workers may be dispersed. The Fordist organization had clear demarcations of tasks that were uniform and standardized: the post-Fordist organization focuses on projects and processes that are unique and tailored to special purposes in the market.

Figure 1.2: Typical differences betweenFordist and post-Fordistorganizations in patterns ofwork, information technologyand location

As computers become ubiquitous and more user friendly, users of information technology have become more aware of the people on their networks: personal interactions through networks have become more useful and significant.17

Software is emerging to serve group and team working processes — ‘groupware’ for computer supported collaborative work (CSCW).18 CSCW allows work on a project to be undertaken in one or several places, at the same or different times, by a group of co-workers.19 The work...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART ONE Intelligence in Buildings

- PART TWO The Market for Intelligence

- PART THREE Evaluating Building Intelligence

- Notes and Reference

- Suggested Further Reading

- APPENDICES

- Index