![]()

Part 1

Local newspapers and local media

![]()

Chapter 1

Attacking the devil?

Local journalists and local newspapers in the UK

Bob Franklin

2005 was a bad year for the local press. The latest news about industry trends included the long-running story about the declining number of local newspapers, their falling circulations and disappearing readers. Breaking news revealed that there were fewer owners on the ground. Five days before Christmas, the Johnston group purchased Scotsman Publications, reinforcing trends across the previous decade towards monopoly ownership of the local press. Other stories exacerbated the glut of bad news. Trinity Mirror, for example, announced a long-expected package of 300 job cuts, while the Northcliffe group triggered speculation about the future of the entire industry by ‘slapping a for sale sign’ on the 110 local newspapers in the group (Cozens 2006: 2): the sign was eventually taken down in February 2006 when the newspaper group failed to achieve its anticipated price (Guardian 20 February 2006: 7). Add to this the news of demonstrations outside the October meeting of the Society of Editors to protest against journalists’ low pay (Silver 2005: 1), as well as concerns about increasing competition from online advertising, Internet-based news services, an expansive local radio sector, the arrival of BBC micro-local news services along with citizen journalists, and it is perhaps unsurprising that at least one media pundit was prompted to pose the question: ‘Has there ever been such gloom in the newspaper industry?’ (Fletcher 2005a: 1). In a final twist of postmodern irony, Sly Bailey, chief executive of Trinity Mirror, cancelled the group’s Christmas party to save money (Cozens 2006: 2). In the national press the mood was little better; at the Telegraph the traditional management Christmas card was replaced by a greetings email (Fletcher 2005a: 1).

But this cocktail of long- and short-term trends should not generate such despondency. The local press has survived endless precocious valedictories by pundits previously. In truth, local newspapers are very successful business enterprises (Mintel 2005). Profits are considerable and expansive, while profit margins (measured as a percentage of turnover) are legendarily high and explain the voracious appetite of groups like Johnston Press for buying newspapers. This, in turn, feeds the growing concentration of ownership in the industry (Milmo 2005a: 21, 2005b: 23). Profits have been sustained in the face of the genuine and long-term decline in sales, by buoyant advertising revenues and a cost-cutting management strategy. But this strategy has reduced the number of journalists, kept their wages low and impacted on the newsgathering and reporting practices in ways that diminish the range and quality of editorial in the provincial press (Barter 2005: 4–5; Franklin and Murphy 1997). These editorial changes provide the real cause for gloom. Local newspapers are increasingly a business success but a journalistic failure. This success and failure are intimately connected.

The UK local press enjoys a distinguished history of journalism, which is placed at risk by current managerial strategies. Chris Lloyd’s (1999) celebratory history of the Northern Echo adopts for its title former editor W. T. Stead’s injunction that journalists should spend their energy ‘attacking the devil’ and championing the causes of their paper’s readers. But cuts in journalistic staff and the growing reliance of journalists on external sources of copy from press agencies (see Chapter 18), the town hall (see Chapter 16) or local interest groups, diminish the prospects for critical or investigative journalism; the contemporary local journalist is less likely to be ‘attacking’ than ‘supping with’ the devil.

Managing decline: fewer papers and fewer readers

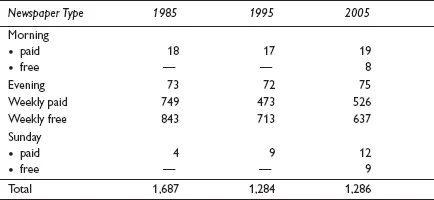

In 2005, there were 1,286 local newspapers circulating in the UK including 27 morning dailies (19 paid and 8 free), 75 evening papers, 21 Sunday papers (12 paid and 9 free), 526 paid weekly titles and 637 free weekly papers1 (Newspaper Society 2005). Longitudinal comparison with equivalent figures across two decades reveals the extent of the decline of the UK press title base across the 1990s and its subsequent relative stability (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Local newspapers: declining number of titles 1985–2005

Source: Newspaper Society database 1985, 1995 and 2005.

Broad comparisons between 1985 and 2005 will foster further despair with an aggregate loss of 401 (24 per cent) titles across 20 years. But Table 1.1 reveals that the last ten years have been a period of virtual stasis in the number of newspapers published. More significantly, it illustrates the marked shifts among the different types of newspapers that constitute the local press. The period since 1995 has witnessed the revival of weekly paid papers to their highest level since 1988 (548 titles), the continued decline of weekly free newspapers to their lowest number since 1995 (713), as well as the emergence of free Sunday and the successful free morning Metro titles (Newspaper Society). But again, stability is evident when each newspaper type is considered as a percentage of the overall local press numbers. In 1985, for example, free weeklies represented 52.3 per cent of the local newspaper total compared to 49.5 per cent in 2005 with equivalent figures for paid weeklies (41.7 per cent in 1985 and 41 per cent in 2005), paid mornings (1.1 per cent and 1.5 per cent), evening papers (4.3 per cent and 5.8 per cent) and paid Sunday papers (0.2 per cent and 0.9 per cent) displaying a similar constancy for the local press mix.

The data concerning circulations are less equivocal and signal that fewer and fewer people are reading local newspapers. At their peak in 1989, almost 48 million local newspapers (47,870,000) were sold each week, but by 2004 this figure was reduced to 41 million – a decline of 15 per cent. Mintel (2005) suggests a loss of 13 per cent in total volume sales between 2000 and 2004. Free papers have similarly declined from 42 million copies in 1989 to 29 million copies distributed weekly in 2004 – a drop of 28.6 per cent even when the 4.5 million weekly copies of the Metro, Standard Lite and MEN Lite are included (see Chapter 14). There is some comfort in the 4 per cent growth in paid weekly sales (Mintel 2005), reflecting the expansive number of paid weekly titles, but the majority of newspaper sectors are experiencing serious and long-term circulation falls.

In 2004, ABC data recorded an increase in circulation for only 7 of the 75 listed evening papers; a year later, 18 of the 20 best-selling evening titles registered a decline. Some papers are losing readers at an alarming rate with the Evening Standard dropping 11.7 per cent in circulation across the January to July period monitored. The Birmingham Evening Mail (–9.5 per cent), the Yorkshire Evening Post (–8.5 per cent), the Sheffield Star (–6.8 per cent) and the Nottingham Evening Post (–5.9 per cent) are experiencing a similar and striking downturn in sales. Two evening papers are enjoying circulation growth, but it is modest: 1.8 per cent at the Belfast Telegraph and 0.2 per cent at the Newcastle Chronicle. Similar downward trends are evident in the morning newspaper market with only the Western Mail, the Ulster News Letter, the Daily Post and the Paisley Daily Express resisting decline among the 20 best-selling papers. All English titles experienced a decline in sales in 2005 and, again, some losses are striking, with the Yorkshire Post selling 8.9 per cent fewer papers than in the previous year. Six of the ten largest Sunday papers (by circulation) experienced a decline (–12.8 per cent at the Sunday Mercury) and even three of the eight new Metro titles registered falling distribution, with three others showing increases of 1 per cent or less (Newspaper Society 2005).

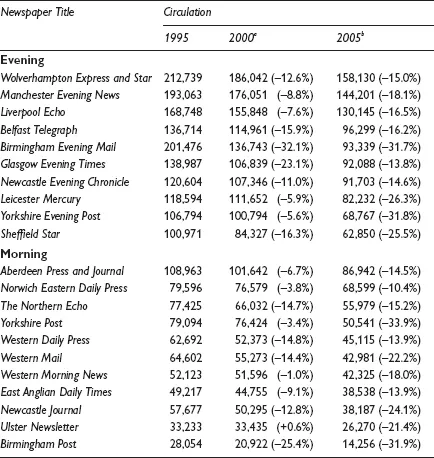

But the dramatic extent of the circulation decline confronting some titles becomes evident only in longer-term comparisons. Table 1.2 compares circulations of key evening and morning titles across the last decade.

Table 1.2 Circulation of selected evening and morning titles 1995–2005

Source: ABC and VFD data from the Newspaper Society website.

Notes

There are some striking figures here. Since 1995, the Birmingham Evening Mail has lost 53.7 per cent of its circulation, the Sheffield Star 37.8 per cent, the Yorkshire Evening Post 36 per cent and the Leicester Mercury 30.7 per cent. The figures for morning titles are less dramatic but also catalogue severe downturns across the period with 49.2 per cent at the Birmingham Post, 33.8 per cent at the Newcastle Journal, 28 per cent at the Western Mail and 27.1 per cent at the Yorkshire Post. Significantly, Table 1.2 reveals that for 17 of the 20 titles, the decline in circulation has been greater in the more recent period since 1995, substantiating that the pace of circulation decline is increasing.

Local newspapers mean business! Advertising, profits and consolidation

Local newspapers remain highly successful and profitable business organisations despite these long-term downturns in circulations and readerships. The explanation of this apparent paradox is the adoption of a business strategy designed to maximise revenue, especially advertising revenue, while minimising production costs. This strategy has delivered high profit margins for the larger newspaper groups and promises continuing business success (see Chapter 8). Mintel’s report Regional Newspapers, for example, claims that ‘future prospects for the UK regional press sector … remain good’ and identifies ‘real growth opportunities’ which provide ‘grounds for confidence in a healthy future for the sector’ (Mintel 2005).

Advertising revenues remain bullish despite declining circulations. Local newspapers effectively enjoy a monopoly in local classified advertising, which constitutes more than two-thirds of their overall advertising revenues (Mintel 2005). A senior local journalist claimed,

the point is, that advertisers in our area advertise in our paper or they don’t advertise at all. And that’s the point. We’ve cornered the market in terms of advertising, unless they go on the television or the radio, which clearly isn’t feasible for local people. As a result, local papers manage to keep up the advertising revenues and even if they only sell four copies of the paper, it keeps making a lot of money and we keep producing it.

(interview with the author May 20052)

In 2004, advertising revenues in the regional press reached £3,132 million, which represented a 20 per cent share of total media advertising revenues, second only to television at 26 per cent but markedly higher than national newspapers (13 per cent), magazines (12 per cent), radio (4 per cent), cinema (1 per cent) and the Internet (4 per cent).3 Local newspaper advertising revenues grew by a healthy 5.8 per cent in 2004. The local press is the only medium that has been increasing advertising expenditure year on year for more than a decade – from £1,963 million in 1995 to £2,762 million in 2000, and more than £3 billion by 2004 (Newspaper Society). It is not only the high levels of advertising revenue which are significant to the business success of local newspapers; equally important is advertising’s contribution to overall revenue which stands at a massive 80 per cent of the overall income of local newspapers compared to approximately 46 per cent for national papers (Mintel 2005).

This sustained income from advertising revenue is the key to the profitability of the local press. In 2003, Trinity Mirror, the largest group by circulation in the UK, returned a profit in its lucrative regional newspaper division of £123.9 million on a turnover of £525 million – a profit margin of 24 per cent (Pondsford 2004: 3). Figures for 2004 reveal that profits at Northcliffe (£102 million), Johnston (£177 million), and other leading groups continue to rise with unusually high profit margins (35 per cent at Johnston), although figures ‘between 25 per cent and 30 per cent’ are typical ‘for many local newspaper companies’ (Dear 2006: 8).

These expansive profits reflect the access of provincial newspaper groups to economies of scale – such as printing and subediting local newspapers at central sites within a group’s ‘territory’ – which are available because the ownership of local newspapers is highly concentrated in a handful of regionally based monopolies. The process of consolidation, which has generated this monopoly structure, has been rapid and particularly marked across the last decade (see Chapter 8). Takeovers and mergers remain a constant feature of the industry. By 2005, for example, the Yorkshire Post had experienced ‘four owners in ten years. In the 240 years before that, it essentially had just one other owner’ (Martinson 2005: 18).

In 1996, ownership of one-third of all regional newspaper companies changed hands (Franklin and Murphy 1998: 19). In December 2002, Newsquest acquired the Glasgow Herald, the Glasgow Evening Times and the Sunday Herald for £216 million, following its earlier purchase of the Newscom group in May 2000 for £444 million, adding titles with circulations of 499,550 to its holdings. Johnston Press has superseded Newsquest as the most acquisitive of groups. In March 2002, for example, Johnston purchased Regional Independent Media’s (RIM) 53 titles with aggregate circulations of 1,602,522. In the last six months of 2005, Johnston spent more than £500 million buying local papers. The spending spree began in August when Johnston bought Scottish Radio Holdings’ 35 titles for £155 million. A month later, the group purchased The Leinster Leader Group for £95 million and the Local Press Group (£65 million), which includes the prestigious Belfast News Letter. In December, Johnston bought Scotsman Publications from the Barclay brothers, a group that includes The Scotsman, Scotland on Sunday and the Edinburgh Evening News. The Scotsman exemplifies the trend for profitability despite falling circulation – a return of £7.7 million in 2004 with sales down from 100,000 in 2000 to 65,392 by November 2005 (Milmo 2005b: 23). On the day Johnston bought Scotsman Publications, the group confirmed it was considering a bid for the Northcliffe local titles recently offered on the market and valued between £1.2 and £1.5 billion (Fletcher 2005b: 7).

One consequence of this merger ac...