This is a test

- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Political Ecology addresses environmental issues which Innis was concerned with, from a contemporary, political economy perspective. They explore a wide range of themes and issues including:

* sustainability

* risk and regulation

* population growth

* planetary management

* impact of humanity on environment

* role of technology and communication.

Case studies provide further insight into issues such as industrial racism, women and development and collective action by highlighting ethical and political questions and providing critical insights into the issues and debates in political ecology.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Political Ecology by David Bell,Leesa Fawcett,Roger Keil,Peter Penz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Negocios en general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER AND THE ENVIRONMENT: DEFINING THE ISSUES

1

GLOBAL ORDER AND NATURE

Elmar Altvater

Introduction

Only in the twentieth century is it possible, for the first time, to speak of ‘world order’. Only during the Fordist phase of capitalist development did the great majority of humankind get integrated fully into global relations. As a result of the commodification of all spheres of life, or what Marx called the ‘real subsumption of labour and nature under capital’, nearly everywhere, all social relations are penetrated by the economic logic of capital valorization. Polanyi observed that ‘the human economy is usually embedded in social relations. The transition from this social form to a society which, quite perversely, is embedded in the economic system was an entirely new development’ (Polanyi 1957a: 135), which, we might add, reached maturity only during the Fordist mode of regulation.

The ‘global orders’ of the millennia and centuries preceding the advent of the capitalist mode of production in Europe had always only encompassed the ‘world’ which was known and accessible at the time.1 To trace ‘world-systems’ to ‘prehistory’ (after the ‘neolithic revolution’) and interpret the rise and fall of world empires and world cultures as long economic, political and cultural cycles lasting several centuries only makes sense if one views the feeble long-distance trade relations and monetary flows (concentrated on a few cities) as the channels of communication of a system. Such a perspective privileges the formal over the real subsumption of social relations under the capitalist social form (Frank and Gills 1993). Before the advent of the modern age in Europe in the ‘long’ sixteenth century, only certain parts of commodity and monetary circulation spanned continents or the whole globe. Up until the nineteenth century, 90 per cent of the active population was working in agriculture and the overwhelming majority of economic activity took place on a local or at best regional level. Wallerstein may be right in concluding that a capitalist world system developed during the last five centuries (Wallerstein 1974; Modelski 1987). But images of the ‘blue planet’ and ‘the unitary world’ (eine Welt) were projected into popular imagery only after the launching of spaceship Apollo in the 1960s made it possible to take photos of our planet Earth. As an economic system, political order, social unit and above all ‘global ecosystem’, the unitary world has been in existence only for a few decades and for this reason the discourse of ‘world order’ has only become more than metaphorical at the end of the twentieth century.

As long as ‘the societal relationship with nature’ was based on biotic energies, on the soil and the fruit it bore, on the speed and range of an ox or horse drawn cart, on the tonnage, manoeuvrability and speed of a sailing vessel and on the art of navigation, the material possibility of overcoming these limits of space and time was slight and the capacity of creating a world order remained restricted. In the twentieth century, however, the extraordinary density of economic and political ties among all regions of the world led to the emergence of world politics, the world economy and global ecological problems. In the world economy, corporations compete against each other at remote production sites and in highly integrated world markets, which only a few decades ago belonged to different worlds separated by geographical barriers. Japanese and German cars competing in Latin American markets—this would have been an absurd idea in the 1950s. The ‘banana war’ instigated by the European Union against cheap ‘dollar bananas’ from Central and South America would have been declared a bad joke twenty years ago. Corporations are not only multi- and transnationalized in core segments of the production process, they must also compare the profitability of invested capital with the interest rate formed in highly integrated international capital markets.

International competition forces corporations to adjust and thus leads to an equalization of production conditions, consumption norms and finally profit rates among previously distant regions of the world. As long as corporations do not produce for local markets only, their profitability must conform to a minimum level given by the interest rate formed in global capital markets. Keynes (1936) still assumed that the setting of interest rates was an indispensable element and a principal expression of national sovereignty. Today nation states have lost their sovereign power to determine interest rates (Zinssouveränität) (Scharpf 1987). The role of nation states changes once economic competition erodes the bases of political sovereignty, that is to say, when under a free trade regime territories can no longer be protected from competition from other regions in the world, when citoyens are no longer identical with bourgeois, and when the political power of states is undermined by market forces. In such a situation nation states and regions try to regain their sovereignty by compensating for what they have lost due to the interest rates, exchange rates and commodity prices with a political programme to boost the ‘systemic competitiveness’ of particular territories (Porter 1990). The reduction of labour costs (or less euphemistically: the reduction of wages and salaries), the creation of positive synergies in networks and technological impulses constitute the main pillars of micro- and macro-economic initiatives.2 Costs must be reduced to stay competitive in given conditions determined by commodity prices, exchange rates and interest rates which are beyond the influence of individual states. In such a context the nation state is being transformed into a competitive state (Wettbewerbsstaat) (Hirsch 1997), which promotes ‘its’ production sites economically and defends them politically against ‘foreign’ producing regions. Such strategies are unproblematic as long as an expanding world market provides the conditions for a positivesum-game. If however zerosum games or even negative-sum games define the rules, competition policy becomes a ruinous race for rationalization (which displaces labour and increases unemployment) and a dangerous strategy of externalizing social and ecological costs.3 In this situation one can observe tendencies towards ‘macro-regionalism’, that is to say the formation of regionally integrated economic spaces (EC, EFTA, CUSFTA and NAFTA), and ‘micro-regionalism’ below the level of nation states. As a result, nation states exhibit signs of disintegration (Cox 1993) and societies are exposed to the ideological stress of modern ethnic conflict.

The post-war order,4 which provided the framework for world politics, lasted less than fifty years from 1945–89. In 1989, the fall of the Berlin wall symbolized the collapse of ‘real existing socialism’ and brought an end to bipolarity. Since that time some have begun to talk about a ‘new world order’ of ‘unipolarity’ (Krauthammer 1991). At the beginning of the twenty-first century—after the ‘victory of the Cold War’ and the ‘end of history’5—there appears to be no alternative to the rationalism of world domination embodied in processes which are guided economically by markets and steered politically by formal democratic procedures. This apparent lack of alternatives expresses the fact that all dimensions of capitalist reproduction are subsumed not only formally but also substantially under the capitalist social formation.

Even if the process of ‘determination’ leaves plenty of room for individual action, ecological restrictions on the future of development have now become a reality. With the creation of an economic world system and a political world order, the ‘metabolism’ of humankind, society and nature has now reached a global scale. The societal relationship with nature is global and its regulation thus requires global rules. The common understanding necessary for the latter’s creation and functioning is, if at all, just now beginning to emerge.

The pursuit of the rationalism of world domination has raised many questions to which new answers must be found within the ‘new world order’ because ‘old’ answers stemming from the period of bipolarity have proven to be inadequate if not counter-productive. Can modernization and industrialization modelled after the ‘North’ and the ‘West’ continue to constitute a realistic societal goal for all societies in all regions of the ‘South’ and the ‘postsocialist’ East? If yes, how should one deal with the failure of development efforts made during the last decades in the politically (not necessarily geographically) defined ‘South’? What kind of regulatory frameworks will have to be agreed upon to ‘order’ the international financial and currency relations which are now out of control? And finally, how should one react to the fact that at the same time as the rationalism of world domination is being perfected, global ecosystems—water, air, land and ice caps—are threatened to be thrown out of balance? In the following pages, I will try to find answers to these pressing questions. For that purpose it makes sense to adopt a historical perspective in order to define the kinds of tasks the present must face in light of the aforementioned problems of world economy, world politics and global ecology.

The social form of surplus production and the energy system

The conquest of global space and the temporal acceleration of economic processes has a long history going back to the ‘neolithic revolution’ which lasted several hundred, if not a thousand years around 6000 BC.6 Only from today’s perspective do the developments in south-west Asia (mostly Mesopotamia), China or Mesoamerica appear as parallel evolutions, which was most certainly not the case (Ponting 1991:37–67), notably because the contemporaries did not know of each other and thus invented gunpowder, the wheel, and the written word independently.

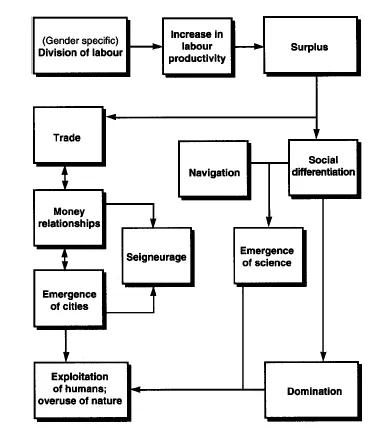

Still, it is possible with the advantage of historical hindsight to discern a logic in the history of human evolution (see Figure 1.1): initiated by what was probably a gender-specific specialization,7 the transition to agriculture facilitated a more intensive utilization of natural resources. Increased labour productivity resulted in a surplus which allowed for social differentiation. With the deepening of the division of labour in society, classes and castes of warriors, priests, administrators, and rulers could form and assume the role of appropriating and distributing the surplus. At the same time, surplus production allowed for an expansion of trade within and, above all, among societies. The production of commodities for exchange and thus the principle of equivalence became a social norm. As monetary relationships spread and intensified, coins were introduced. Those able to exercise monopoly control over coinage were in the position to make a profit based on the difference between the nominal and the real value of currency (seigneurage).8 The organization of production, distribution and storage of surplus became the source of power and privilege for the elites in the city. The accumulation of surplus constituted a project of domination which neither in Mesopotamia nor in Central America, Eastern Asia and Europe stopped short of the over-exploitation of human beings (super-exploitation) and nature (environmental degradation). Salinization (in Sumer), soil erosion (in China and Mesoamerica), deforestation (in Indus valley and the Mediterranean) destroyed world empires which we continue to admire because of their cultural achievements (scriptures, monuments, discoveries in astronomy). The disregard for ecological limits has a history which is much longer than that of industrial society. Nevertheless, the destruction of nature remained restricted to the local and regional level and never reached global proportions.

The spatial dimensions of ecological problems are defined by the reach of energy systems. In modes of production based on biotic energy, labour productivity can grow only to a certain, limited level. The speed of a human being, a horse, or an ox can only be increased to the point of physical exhaustion. Yet the transition to fossil fuels and the concomitant technological systems of energy transformation (the industrial forces of production) and social formation (the capitalist mode of production) constituted a qualitative advance in human history which in this case is rightly called revolutionary. Since the late eighteenth century, the resort to fossil energy sources, ‘exosomatic’ forces (Lotka 1925; Smil 1993:3), facilitated a quantum leap in the speed and reach of human activities. Enormous growth in labour productivity and social surplus production were made possible.9 According to calculations by Angus Maddison, the average GDP per capita in international dollars (1980 prices) of OECD countries grew from $1, 817 to $10,205 between 1900 and 1987, a six-fold increase, while in the USSR, which started off at a lower level of aggregate production, GDP increased by a factor of 7.45 during the same period (Maddison 1989:19).

Figure 1.1 Elements of transition during the ‘neolithic revolution’

In this context Nicolas Georgescu-Roegen (1971, 1986) talked about a ‘Promethean revolution’ in productivity growth which was experienced first by European, then by ‘neo-European’ humankind in the re-orientation of its energy system to fossil fuels and the transformation of its mode of production and form of social and political organization. Humankind thus evolved from agriculture, which emerged from the ‘neolithic revolution’, to modern industry (Georgescu- Roegen 1971:292). In 1870, 49 per cent of the labour force in OECD countries worked in agriculture compared to only 6 per cent in 1987 (Maddison 1989:20). In his analysis of the ‘process of production of capital’, Marx demonstrated how the ensemble of motion, transmission, and machine tool machinery in heavy industry made it possible to produce relative surplus value by means of the real, not just the formal subsumption of labour under capital (Marx 1936:342).10 This principle expresses a type of productivity growth which is no longer slow and geographically restricted (as in agricultural societies) but global and continuously intensifying, driven by the competition of individual corporations on capitalist markets.11

The fact that ever since the discoveries in the ‘long sixteenth century’ (Braudel 1977), Europe could dominate the rest of the world even though in the thirteenth and fourteenth century Europe was still a ‘backward’ continent compared to the Chinese and Indian empires,12 can be explained by the disintegrating tendencies within ‘competing’ empires (Frank and Gills 1993; Ponting 1991) and by the European expansion across the Atlantic into the Western Hemisphere, where conquest faced comparatively little resistance (Crosby 1986). Europe enriched itself during the centuries of ruthless exploitation following the discovery. Similar to Laurian silver in the case of Athens, Latin American silver became a significant factor in primitive capitalist accumulation in Western Europe. The importance of silver can be judged by the fact that in the nineteenth century the Ottoman empire, the Latin American states, the USA and tsarist Russia were all indebted (sometimes to the point of bankruptcy) to the European colonial powers (Kindleberger 1985:213).

The colonies also benefited invaluably from the emigration of the surplus populations of Europe who could be induced to leave their countries for the Americas, Australia, New Zealand and, to a lesser extent, Africa. Between 1820 and 1930 Europe managed to ‘rid itself of about 50 million people. The costs of the accelerating process of accumulation were thus externalized. Indeed, these social costs were almost miraculously transformed into social benefits, for the colonies now had considerable purchasing power, developed new markets, delivered raw materials and absorbed capital. A virtuous cycle was thus set in motion. Capital accumulation fed colonial expansionism while the colonial expansion of Europe supported the internal accumulation of capital. In the sixteenth century, Europe became the hegemonic continent within the world system and retained its status up to the twentieth century. The functions of hegemony continued to be tied to nation states which got entangled in serious conflicts (as predicted by the theory of hegemonic cycles (Modelski 1987)), which finally culminated in two world wars and resulted in the weakening of not only the defeated but also the victorious European nations (Britain, France). Since the mid-twentieth century, the exercise of global hegemony has been in the hands of the United States.

Capital accumulation, global expansion, the subjection or extinction of other cultures and the exercise of political hegemony were thus mutually contingent processes. What distinguishes the new world system from older ‘world empires’ is the globality of order. The ‘real subsumption of labour under capital’...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- TABLES AND FIGURES

- CONTRIBUTORS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION

- Part 1: THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER AND THE ENVIRONMENT: DEFINING THE ISSUES

- Part 2: ECONOMICS, SOCIETY AND ECOLOGY

- Part 3: PLANETARY MANAGEMENT: TOMORROW’S WORLD

- Part 4: ENVIRONMENT, GENDER AND DEVELOPMENT

- Part 5: CONSUMPTION: WORK AND AFFLUENCE

- Part 6: ECOLOGY AND POLITICS