![]()

Part I

Theories About Planning During Crises

![]()

1 Mass Immigration and Rapid Urban Growth as Crisis Situations

Consider the following scenario: you are a senior planner with the US federal government, in the Department of Housing and Urban Development. You wake up one morning to learn from the news broadcasts that due to a foreign policy change or an imminent catastrophe somewhere in the world, your country is to open its gates to 12 million refugees immediately, and will take in 50–70 million people in three to five years. This is equivalent to or higher than the entire population of a large European country such as the UK, France, or Italy. You wonder: how can the government develop policies to ensure adequate management of this avalanche? What could be the impacts on society and its resources? How can cities, towns, and neighborhoods align themselves?

As a planner, you say to yourself: a grand challenge for planning! The opportunity our profession has been looking for! But when you rush to dig up your planning theory notes and books in search of models and techniques, you begin to wonder: can planning help in a time of crisis?

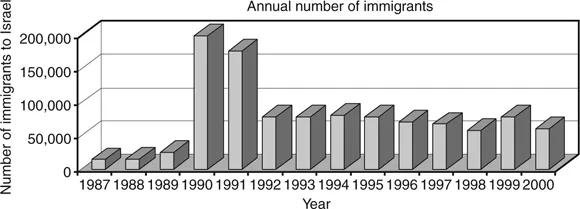

This US morning-news scenario illustrates the magnitude of the crisis that Israeli planners and decision-makers faced. Starting in November 1989, and intensifying in early 1990, Israeli planners who turned on their radios heard about an imminent change in policy of the Soviet government toward its Jewish citizens. As international conditions changed, the doors of the USSR were opened for emigration. In retrospect we know that within three years, 500,000 immigrants were added to Israel’s 1989 population of 4.5 million, and by 2000 approximately 1 million will have arrived (see Figure 1.1). But projections in 1990 oscillated. At first they expected more modest numbers than those that were, in fact, to arrive, but soon they swung to the other extreme and expected much higher numbers. Uncertainty was the name of the game. The impacts on almost every aspect of society and the economy were expected to be considerable – but what these would be was not known.

The challenges were to supply the housing, physical infrastructure, social, educational, and health services necessary to absorb the sudden influx of immigrants, and to increase employment opportunities. A crisis of this magnitude was rare in peacetime in any Western country. Many crisis situations are negative: natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, wars or acts of terror; social upheavals such as inner-city riots; or economic crises, such as the closure of a major plant in a small town. The policy and management literature on crises tends to focus, almost exclusively, on such negative crises, with natural disasters receiving the most attention (this may change after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack in the USA). Because disasters are certain to occur somewhere, sometime, and when they do they may sink lives and investments, it is rational to develop plans for facing such situations in order to minimize the damage.

Figure 1.1 Annual number of immigrants.

But crises in cities, regions, or nations may also be positive events – situations that hold vast opportunities but are replete with uncertainty and turbulence. Examples are the reunification of Germany, mass immigration to Israel, or a large, lucrative plant’s decision to locate in a small town along with hundreds of employee families.

Many crises may be classified as mixed situations, for they present a grand opportunity in the eyes of some, but also the threat of great damage, should public policy fail to supply appropriate answers. A good example of a mixed crisis on both national and local levels is the collapse of the Soviet Union, which has had immense impacts on all spheres of life in that country and in neighboring states. Some of its impacts have been positive, with grand opportunities unleashed for individuals, businesses, and governments; but some have been negative, with the increase in crime, the reduction of personal economic and social security, and the introduction of major uncertainties in many spheres of public and private life. Another example might be a sudden rise in illegal immigration that impacts both negatively and positively on a nation or a region. And finally, there is the more commonplace example of the influx of new residents to a particular city or region, an influx that “growth management” tools have been unsuccessful in controlling. Many local residents may see such a migration as a threat, even though this influx also brings with it many positive effects.

Why are Crises Interesting to Planners?

In countries with a post-industrial economy, situations of turbulence and uncertainty are no longer rare (Rosenthal and Kouzmin 1997). An innovation may last only a few months to be replaced by a competitive one elsewhere in the world; instant information can move markets and populations; national and international alignments change at an accelerated pace; high-risk technologies are prevalent; and national and international organizational structures have become increasingly complex. Households, cities, regions, private and public organizations must all contend with the rising likelihood of having to face a major crisis. As two researchers into crisis management have put it: “In today’s world, it is no longer a question of whether a major crisis will strike any organization; it is only a matter of when, which type, and how” (Mitroff and Pearson 1993: xiv).

But to date, theorists of public planning (as distinct from theorists of corporate management) have devoted little attention to the role of planning in times of crises. Of those who have, most doubt that there are recognized planning approaches for handling crises, or that planning can be of much help – a point to which we shall return in Chapter 2.

During crises, dilemmas in planning take on a sharpened edge and expose major issues that may be on a “back burner” in non-crisis situations. The study of crises therefore holds important lessons for planning. Planners and public policymakers should be interested in knowing whether there are tools to guide situations of uncertainty and turbulence, or whether crises are indeed accompanied by “planning failure.” How do crises affect planning? Do they challenge its validity or, conversely, strengthen it? Do crisis situations require types of planning that are inherently different from planning in non-crisis situations? What roles can professional planners play vis-à-vis other actors in the process? Will they be shunted aside as irrelevant, or will their skills be in high demand? Members of the planning profession, recognizing that crisis situations are likely to place dilemmas of heightened ethical conflict at their doorstep, might be interested in how planners who have been faced with a crisis have handled such tough conflicts.

The academic purpose for undertaking this research is to add to the sparse research on the role of public planning in times of crisis. The mass immigration crisis in Israel has turned out to be a large-scale laboratory for studying the response of planners and decision-makers to positive crises. By analyzing the modes of response of decision-makers and planners to the crisis situation, following its various phases, and looking at some of its outcomes, I hope to be able to draw lessons that can enhance our understanding of planning practice in situations of crisis. The more practical purpose is to help agencies prepare for crisis situations, both “negative” and “positive,” and especially, to encourage public agencies to view crises as rare opportunities for positive change.

Mass Immigration as a Potential Crisis: A Cross-National View

Mass immigration from the less affluent to the more affluent countries is a world-wide phenomenon. As Sassen (1994, 1998: Chapter 2) and Hall (1996) argue, the intake of immigrants is most frequent from neighboring, less affluent countries (such as East European to West European countries, and South American to North American countries). There is also much intake from countries that bear some political or ethnic kinship to the receiving country (such as former-colonial Algeria to France, and East European Germans repatriated into the united Germany). Immigration trends respond quickly to political and economic changes; for example, soon after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, economic and political disparities among the formerly socialist countries led many Ukrainians, relying on both linguistic kinship and shared past-political experiences,1 to seek greater security in Poland.

Had immigration patterns been a reflection only of the demand to emigrate and the capacity to pay for the trip, we might have seen population movements of hundreds of millions across borders in search of a better life. But most industrialized (or post-industrialized) countries have placed tight administrative caps on immigration, seeking to regulate the number of immigrants and their socioeconomic status, age, health, and ethnic composition. Through such controls, these countries hope to avoid the perceived turbulence of an uncontrolled influx of immigrants.

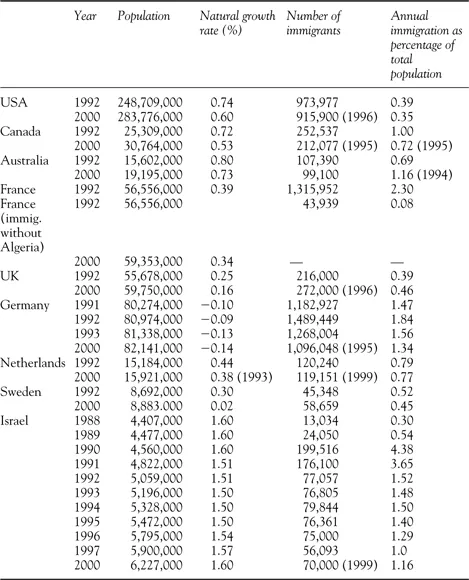

Let us look at some comparative numbers (see Table 1.1). In a typical year such as 1996, the USA – a country of some 265 million people in 50 states – took in approximately 900,000 immigrants. This represents an addition of only 0.35 percent to its total population, slightly down from 0.4 percent in 1992. Canada, which in the past has had a more open door policy toward immigrants compared with most other advanced-economy countries (1.00 percent in 1992), has been reducing its intake rate to 0.7 percent in 1995 (212,000 immigrants). The UK’s 1996 rate was 0.46 percent, similar to its 1992 rate, allowing in 272,000 immigrants. Sweden allowed in some 40,000 immigrants in 1996, adding 0.5 percent to its population, a rate almost identical to its 1992 rate. The Netherlands was willing to absorb more than most other European countries – 0.77 percent. If we exclude Israel, Germany, and France, to be discussed as special cases, the country with a consistently high rate of immigration is Australia, which in the 1990s was still willing to take in immigrants. In 1994 they accounted for a 1.2 percent population growth rate.

From these numbers, one can deduce that most advanced-economy countries have sought to protect themselves from mass immigration, as well as from the crises that might ensue were the intake to reflect demand. However, immigration in reasonable numbers usually creates positive economic and cultural change, especially if it is politically and socially desired (Carmon 1996: 12).

Recognizing this, a few advanced-economy countries have from time to time adopted a policy of a more generous immigrant intake. Some countries like the USA, Canada and Australia have in the past done so for economic-development reasons. Canada and Australia still maintain this policy, albeit on a smaller scale than before. Others have taken in large numbers of immigrants for political reasons. An example is France, which in 1992 had Europe’s highest percentage of population increase because of immigration – 2.4 percent. This reflected its political and cultural links with North Africa. By contrast, France’s immigrant intake from countries with which it had no special relationship was low. Among advanced-economy nations, few have an ideologically driven immigration policy. Germany and Israel are the outstanding examples.

Table 1.1 Rates of immigration in nine advanced-economy countries

Sources:

The Europa World Yearbook 1998, Europa Publications Limited, London

UN Statistical Yearbook 1992, New York, 1994

US Government – World Factbook 2000

Israel Statistical Yearbook 2001

Where the latest available dates for particular subjects is other than 2000, the year appears in parentheses.

Since the collapse of the Berlin Wall and unification, Germany has had a policy of repatriating “ethnic Germans,” in addition to its reluctant intake of immigrant workers. These ethnic Germans were citizens of the former Eastern Bloc countries, the so-called Aussiedler immigrants (and are not to be confused with the residents of the former East Germany; Jones and Wild 1992). In 1991 this policy added 1.5 percent to Germany’s population, in 1992 a record 1.8 percent, and in 1995 it tapered down to 1.3 percent (see Table 1.1).

Israel, of all Western countries, is unique in its consistent open door policy toward specific types of immigrants (see p. 13). However, as we shall see in Chapter 3, even though this policy has always been on the books, in 1989 no one expected mass immigration. It began in early 1990. Israel was to take in the largest number of immigrants relative to population size compared with any other advanced-economy country. In 1990 the population increased by 4.4 percent and in 1991 by 3.7 percent. In subsequent years the rate declined, to only 1.0 percent in 1997, but increased somewhat in 1999. Another immigration wave is not unthinkable.

When comparing the impact of mass immigration on Israel and Germany, and indeed, in comparing Israel with any other advanced-economy country, one should take into account the relative size of the population, the economy, the average individual wealth and the available land resources. (In Chapter 4, I present these indicators for 12 countries.) If we focus on the Germany–Israel comparison, we see that in 19902 Israel had about 1/15 of Germany’s population, Israel’s GNP per person was about half of Germany’s, and the lowest of all the countries in the table. The size of Israel’s economy was approximately 3 percent of Germany’s and the lowest in the table. The only ostensibly similar datum between Israel and several other European countries including Germany is population density. But in the future Israel will become the most densely inhabited country among the group because its natural growth rate, excluding immigration, is much higher than any other advanced-economy democratic country. Furthermore, the comparison should perhaps discount Israel’s stark Negev Desert which takes up over 50 percent of the land area...