![]() Part I

Part I

Formation![]()

Chapter 1

City: Culture: Nature

The New York Wilderness and the Urban Sublime

Richard Plunz

In their new Foreword to the 1977 edition of The Intellectual Versus the City (1962), Morton and Lucia White point to the deepening crisis of the American city as further evidence of the “ambivalence or antagonism” toward the city that their research had attempted to demonstrate had always existed in American arts and letters. But a re-reading of the Whites’ text today does not necessarily have to lead to the same conclusion that they reached in 1962, when the process of American post-war de-urbanization was still being expedited with maximum dispatch, and with the resultant urban degradation and suburban dispersal still fresh in people’s eyes and minds. Indeed, as we move into another era it is possible to see the Whites’ exercise in a somewhat different light, cast by a new historiographic understanding of the enormous scale and intensity of the de-urbanization strategy from the New Deal onward, tempered by our having moved from this first post-industrial crisis to a second or even third today. Now we can more clearly see that by the end of the 1950s, de-urbanist revisionism had penetrated the academic world, such that urban historiography began to devalue the role of the city in the development of our national culture.

The 1930s’ post-industrial economic remedies entailed invention of a culture of consumption on an unprecedented scale, linked inextricably to urban dispersal through suburbanization. Within this reconfiguration, which was highly motivated by political ideology, the old city of density and propinquity could not function as the incubator for the new society. A new historiography had to be found which redefined American culture as anti-urban to validate the new ideology. In particular, works like The Intellectual Versus the City consciously or unconsciously served such purposes. Now it is important to reconsider this period, to reassert that cities large and small served as the crucial incubators of American culture; and to verify that historical discourse relative to the virtues of city and country was far more complex than the post-war revisionists would lead us to believe. In this regard, a re-reading of the texts of many of the Whites’ urban “protagonists” provides us with a complex intellectual reflection on the nature of American culture in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Given that American cities were growing exponentially like everywhere in the industrializing world, one would expect this process to raise doubts about the course of urban events, producing an important debate about the viability of the city. Notably, however, there was little by way of urban rejection until well into the twentieth century.

An important ingredient for this re-reading is the relation between city, culture, and nature. It is true, perhaps, that a big difference between the European and American approaches to the idea of the industrial city had to do with the conception of nature. One line of reasoning allowed that if Europeans had “culture,” Americans had “nature,” presenting a very real psychological divide. But even this is not exactly true: more precisely, the Americans had “wilderness.” And in the formative period of nineteenth-century American urban culture, this wilderness was seen as a symbiotic force in urban development. American nature was not placed in a confrontational stance to urbanization. It was not the antidote to the American city deployed by the early European modern movement, just as it was not the antithesis of urbanity as deployed by the post-moderns.

This chapter will focus on the relationship between New York City and the spectacular wilderness of the Adirondack region of New York State. It was there, and especially in the Keene Valley, where between 1868 and World War I a formidable concentration of urban intellectuals congregated. This was a phenomenon unique for its scale and diversity in the American experience. The evolution of the Keene Valley intellectual community over those six decades followed closely the evolution of intellectual sensibilities regarding nature and the city during the same period; and more precisely, the changing self-image of urban intellectuals during the formative years of New York’s development as the North American metropolis.

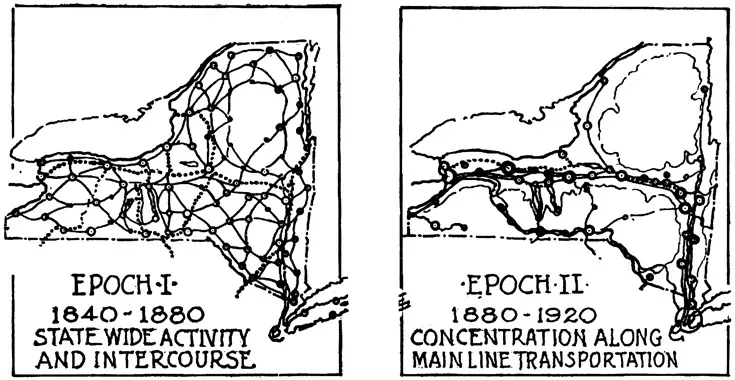

By 1810, New York City had definitively moved to its position as the largest city in North America having by then exceeded Philadelphia in population. More than Philadelphia, New York City took on certain aspects of what one might call a “city-state;” and indeed the State of New York had also exceeded the State of Pennsylvania in population.1 The aphorism “Empire State” became popular. It had to do with the fact that New York City lay at the head of a 350 mile long metropolitan corridor, to the contemporary mind very much an “Empire.” Stretching up the Hudson River to Troy, which was as far as the ocean-going ships could reach, it then turned westward along the Mohawk River to Buffalo and the Great Lakes. This natural watershed corridor was reinforced by construction of the Erie Canal completed in 1825; later by the railroad completed in 1842; and then by telegraph completed in 1846.2 Thus the first North American “megalopolis” developed along this route, comprising a series of cities that were large by early nineteenth-century standards. Such was the growth of the corridor that by 1875 it contained one-half of the State’s population; by 1920 over 80% in spite of the fact that it represented only 20% of the State’s geographic area.3 The cities of the corridor were wealthy and culturally sophisticated industrial centers, very much interconnected along the transportation and communication spine with New York City, which of course remained a primary catalyst for this configuration. New York City’s commercial preeminence was also reinforced by the Champlain Canal, which connected northward from Albany to Lake Champlain in 1823 and extended to the Saint Lawrence by 1843. Thus by the mid-nineteenth century the Port of New York had been connected strategically with the Saint Lawrence basin, Montréal, and the North Atlantic via this inland route.

Incredibly, however, as late as the 1850s, within this same territory of the “Empire State” lay the largest unexplored region within the eastern United States, whose natural environment, while differing from the far western wilderness, easily rivaled it in terms of spectacular landscape. So remote was the region that it was not until 1838 that it acquired a Euro-American name, the “Adirondack Group.” This was based on a Native American appellation transliterated by the state geologist Ebenezer Emmons (1800–1863), who made the first geological survey in 1836.4 Indeed, until the second half of the nineteenth century the area might as well have been in the far west as far as New York City was concerned. This situation changed quickly with improved transportation along the metropolitan corridor. Soon thereafter, the intellectual “discovery” of the Adirondack region followed, consequent to the emergence of the new urban culture. Today the region is the Adirondack Preserve, a state park that comprises more than six million acres and which, if taken alone, would equal or exceed the area of six of the original thirteen English colonies, or for that matter, well over half the area of Denmark.

1.1 Two stages of the urbanization of New York State published in Report of the Commission of Housing and Regional Planning, 1926.

Although the Adirondacks were isolated there was subsistence settlement in the early nineteenth century, much of it hidden away in remote valleys and totally dependent on local agriculture, lumbering and mining. This early population came primarily from New England in the early nineteenth century during the so-called “Yankee Invasion.”5 By mid-century this Yankee culture was marginalized and isolated relative to the culture of the new metropolitan Hudson-Mohawk corridor. After one or two generations, the sparse Yankee population lost contact with the urbanizing state and, more importantly, with the cultural changes that were being wrought by the industrial revolution and urbanization. In 1837 the New York Mirror summarized this phenomenon succinctly:

It seems strange to find so wild a district in “one of the old thirteeners,” the “empire state of New-York.” But the Erie canal, in carrying emigration westward, has retarded the improvement of this region at least thirty years; by not only diverting the tide of new settlers, but preventing the increase of population among the old ones, by luring off the young men as fast as they become old enough to choose a home for themselves. Some, however, seem so attached to the woods and streams of their native mountains, that no inducement could lure them to the prairies.6

Thus the remnants of the Yankee Invasion came to represent an archaic human landscape as important to the intellectual “discovery” of the Adirondacks as the natural landscape.

Indeed, not all of the original Yankees stayed. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Adirondack region had lost population to the urbanizing areas. New York City was growing phenomenally, not only from foreign immigration but also from internal reset-tlement as rural areas declined.7 The culture of those left behind fascinated the new urbanites who began to rediscover the rural regions. The human and natural landscape that the urban intellectuals discovered was more wild than several decades earlier, as the early settlement and exploitation of the natural resources was abated.

I The “Central Park of the World,” 1837–1875

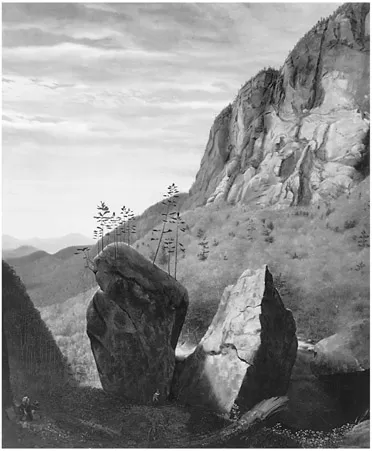

The intellectual discovery of the Adirondacks can be traced to 1835, when the painter Thomas Cole (1801–1848) began to visit the area around Schroon Lake. His painting Schroon Mountain was shown at the National Academy of Design in New York City in 1838,8 setting a precedent for many artists over the next decade who drew attention to the existence of an extraordinary eastern wilderness largely unknown. In 1837, the painter Charles Cromwell Ingham (1796–1863) accompanied geologists on the first recorded ascent of Mount Marcy, painting on site his depiction of Indian Pass called The Great Adirondack Pass, Painted on the Spot. It was shown at the National Academy in 1839.9 Interest in such landscapes went beyond romanticism or nostalgia for a pre-urban society. The new painting was intertwined with developments in the natural and social sciences such that old boundaries were being transgressed so that geology, landscape painting, and morals could be part of one and the same investigation.10 And this speculation could come only from the new urban culture that was evolving. When confronted with the Adirondack “discovery,” the urbanites were incredulous. In the case of the Ingham painting, the writer Charles Fenno Hoffman (1806–1884) went to Indian Pass later on in 1837, to verify if indeed such a landscape existed. This he confirmed in his series of articles for the New York Daily Mirror in which the natural phenomenon is presented as follows:

I must adopt a homely resemblence to give you an idea of the size of the rocks and their confused appearance in this part of the defile; you may imagine, though, loose boulders of solid rock, the size of your tall city dwelling-houses, hurled from a mountain summit into a chasm a thousand feet in depth, lying upon each other as if they had fallen but yesterday.11

Thus, in this first journalistic account, the Adirondack “discovery” is related to an urban metaphor so that urban readers could comprehend the remarkable landscape: in the same way that the geologist could appropriate the depiction as scientific knowledge; or the theologian as moral representation. With this precedent began the evolution of a complex interchangeability between urban and wilderness metaphors within nineteenth-century cultural paradigms. Eventually the city itself would come to represent a natural sublime.12

The relationship between the “second discovery” and the city was highly dependent on emerging urban cultural institutions that could commodify nature for the new urban population. Both Cole’s and Ingham’s “discoveries” were immediately shown at the National Academy of Design. Hoffman’s journalistic account was immediately published in the Daily Mirror. There was the tendency to possess or even colonize the new nature, rather than to act simply as voyeur. The most famous early Adirondack intellectual encounter was known as the “Philosophers’ Camp,” organized at Follensby Pond near Saranac Lake in August 1858, with several members of the Saturday Club from Boston.13 Included were Ralph Waldo Emerson (1807–1873), by then the principal American man of letters; Louis Agassiz (1803–1882), the famous Swiss naturalist who was based in the United States since 1846; Professor Jeffries Wyman (1814–1874), an American naturalist; John Holmes (1812–1899), brother of the famous justice Oliver Wendel Holmes; Dr. Estes Howe (1814–1887), a prominent physician; Judge Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar (1816– 1895); James Russell Lowell (1819–1891), the poet laureate of the eastern intellectual establishment; and William J. Stillman (1828–1901), the artist and journalist whose famous painting documented the event.

1.2 Charles Cromwell Ingham, “The Great Adi...