This is a test

- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Aspects of British Political History 1914-1995

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Aspects of British Political History 1914-1995 examines all the major themes, personalities and issues of this important period in a clear and digestible form. It:

* introduces fresh angles to long-studied topics

* consolidates a great body of recent research

* analyses views of different historians

* offers an interpretive rather than narrative approach * gives concise treatment to complex issues

* is directly relevant to student questions and courses

* is carefully organised to reflect the way teachers tackle these courses

* is illustrated with helpful maps, charts, illustrations and photographs.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Aspects of British Political History 1914-1995 by Stephen J. Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

INTRODUCTION TO BRITISH POLITICAL HISTORY 1914–95

Like its predecessor, Aspects of British Political History 1815–1914, this book is intended to introduce the reader to a range of interpretations on modern Britain. It is designed to act as a basic text for the sixth-form student and to introduce the undergraduate to the increasingly wide range of ideas and research. I hope it will also capture the imagination of the general reader who likes to go beyond narrative into the realm of debate.

Why political history? And what does it mean? During the 1970s and 1980s there was an outpouring of books specifically on social and economic history, a departure from the older type of text, which aimed to cover all areas but within the broad context of political history. To some extent the focus on social and economic history is part of a process of establishing a new balance. In the words of G.R.Elton, the reaction against political history, ‘although often ill-informed and sometimes silly, has its virtues. These arise less from the benefits conferred upon other ways of looking at the past, than from the stimulus given to political history to improve itself.’1

Political history now seems to be making a determined comeback, although in a more eclectic form, covering a wider spectrum and drawing from social and economic issues. It is also based more on controversy and debate and less on straight narrative.

Political history may be defined as ‘the study of the organisation and operation of power in past societies’.2 It focuses on people in positions of authority; on the impact of their power on the various levels of society; on the response of the people in authority to pressures from below; and on relationships with power bases in other countries. The study of political history fulfils three functions. One is the specific analysis of the acquisition, use and loss of power by individuals, groups, parties and institutions. A second is more generally to provide a meeting point for all other components: social, economic, intellectual and religious—these can all be brought into the arena of political history. But above all, political history offers the greatest potential for controversy and debate. As Hutton maintains, ‘More than any other species of history, it involves the destruction of myths, often carefully conceived and propagated. No other variety of historian experiences to such a constant, and awesome, extent, the responsibility of doing justice to the dead’.3

The rest of this chapter will outline the main political issues covered in this book before considering two general themes which run through the twentieth century as a whole.

THE MAIN POLITICAL ISSUES 1914–1995

The period opens with the First World War (Chapter 2), in which Britain played a crucial military role: she increased her land-based commitment on the Western Front to equal that of France and did more than any other power to bring about the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in a war on the periphery. The surprising development of the war was that there were few major naval engagements, but British seapower ultimately proved crucial in the blockade against Germany in 1918. Overall, Britain played a more pivotal and varied military role in the First World War than in the Second. The impact of the war on Britain was considerable, expanding the scope of Government power and authority. There also occurred an upheaval in party politics resulting in the split in the Liberal party between Asquith and Lloyd George and the emergence of a coalition under the latter in 1916. The war provided Lloyd George with a launch into peacetime political ascendancy up to 1922, although ultimately he fell because of the lack of a party-political base. Chapter 2 also deals with the paradoxical impact of the war on each of the political parties, ultimately so different from what seemed most likely at the outset. It looks at the complex impact on the economy and society. In some ways the war acted as a radicalising force, while in others it accelerated, or reversed, pre-war trends. Such a traumatic experience was bound to have a wide range of contradictory results.

Chapter 3 examines the fortunes of the Liberal party. One of the great institutions of the nineteenth century, this had evolved out of the Whigs during the 1860s. The Liberals had alternated in power with the Conservatives, then experienced a bleak twenty-year period after 1885 before winning a landslide in 1906. A major theme of the period 1914–39 was the Liberals’ decline as one of the two major political parties. Explanations for, and the implications of, this decline are considered. Was it already apparent before 1914? Was it the direct consequence of the First World War? And was it continuous—or were there periods of intermittent recovery?

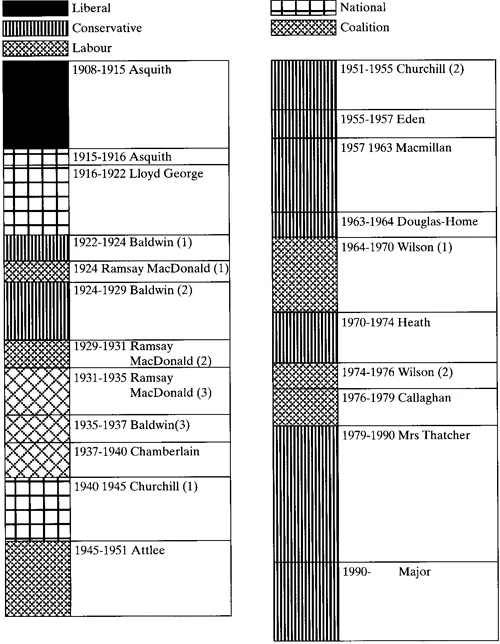

Figure 1 Prime Ministers 1908–95

The counterpart to Liberal decline was the rise of the Labour party. This was relatively slow between 1900 and 1914, when it averaged 30 to 42 seats in Parliament. The First World War saw Labour make the necessary electoral breakthrough as a result of the 1918 Representation of the People Act and the decline of the Liberals. Labour was able to form its first government in 1924 because of a unique set of circumstances, dealt with in Chapter 4. As a minority government, dependent on Liberal support, it was inherently vulnerable. Its record in office was one of constraint and cautious achievement, but this was interrupted by a series of crises which brought about an early general election and a Conservative landslide.

The real beneficiaries of the upheaval of the First World War were the Conservatives, who dominated the political scene for two decades (Chapter 5). They were in power from 1922 to 1923 and between 1924 and 1929, while they also controlled the National Governments between 1931 and 1940. Above all, they scored huge election victories in 1924, 1931 and 1935. Part of their appeal was their claim to be the party of moderation and consensus, a role which Baldwin played convincingly and with skill. In large measure, however, the success of the Conservatives during this period was also due to the problems facing the Liberals and Labour. Baldwin also appeared to score a major victory in his handling of the 1926 general strike. This had roots which went deep into the crisis of the coal industry as well as the overall economic problems experienced by Britain between the wars. Chapter 6 analyses these long-term causes and the more immediate factors which turned a dispute within the coal industry into a general strike. There were clearly two sides in the conflict and battle-lines were carefully drawn between the Government and the Trades Union Congress (TUC). The population at large tended to polarise into support and opposition, and these poles often related to social class and occupation. It is, however, important to avoid too stereotypical an analysis. The eventual failure and long-term effects of the General Strike are also considered, allowing for variations in interpretation.

The General Strike did not, however, damage Labour too fundamentally because MacDonald was back in power in 1929 (Chapter 7), this time with Labour as the largest single party in the House of Commons, although lacking an overall majority. The first eighteen months of this government were relatively promising and MacDonald's achievements were more substantial than they had been in 1924. He was, however, affected by an economic disaster which was initially beyond his control. To the inexorable increase in unemployment before 1929 was added the impact of the Wall Street Crash on Britain's finances. MacDonald's response to the apparent threats to the stability of the Bank of England was to appoint the May Committee in 1931 and to act upon its recommendations for heavy cuts in public expenditure. This split the Labour party, the majority withholding its support for its leader. MacDonald therefore formed a National Government, consisting primarily of Conservatives, but also with a few Labour and Liberal ministers. Chapter 7 considers three key issues related to these events. Was MacDonald misguided in his acceptance of the May Report? Did he subsequently betray the Labour party in establishing a National Government? And did the 1931 crisis have any serious long-term effect on the Labour party?

Although it was Labour which was unfortunate enough to be caught out by the 1931 crisis, all three political parties were bemused by Britain's economic problems. In retrospect, this is not really surprising, since the inter-war economy was in a state of upheaval (Chapter 8). One feature was the decline of the traditional, or staple, industries, especially iron and steel, shipbuilding, coal and textiles. Another was the rise of several new industries, including motor vehicles, chemicals and electricity supply and manufacturing industries. The changing regional bases of industrial growth and decline were so extensive that they profoundly affected the patterns of unemployment, which reached a peak during the 1930s. This eventually fell back by 1938, although the extent of government responsibility for this is debatable. Ironically, this was also a period of growing prosperity for a large part of the population, which casts a large question mark over whether the thirties was really the ‘Devil's decade’.

Meanwhile, British foreign policy had to deal with two major powers which were affected in very different ways by the First World War— Germany and Russia (Chapter 9). The former was the subject of the Treaty of Versailles, in which Britain played a vital—and controversial— role. This was followed by an attempt to shore up the post-war settlement in the form of collective security which, however, contained a significant number of defects. These included a huge gap in the arrangements to contain Germany: unlike France, Britain confined its policy of containment to western Europe and expressed a total unwillingness to become involved in the east. This was largely because of a persistent suspicion of Soviet Russia which cancelled out the more positive relations developed with and around Germany.

Collective security was therefore inherently vulnerable. During the 1930s it was replaced by appeasement as Britain's response to European problems and threats (Chapter 10). To a certain extent, however, it had always been one of the strands of collective security and was therefore in part a logical consequence of it. The practical results were that Britain put pressure on France to cut her security connections with eastern Europe and to accept without serious objection Hitler's remilitarisation of the Rhineland in 1936, his Anschluss (1938), and the annexation of the Sudetenland to Germany in 1938. Chamberlain's record at the Munich Conference in September 1938 has attracted more controversy than any other action in foreign policy over the whole century. The theories behind this are therefore considered at length, as are those for the reversal of appeasement in 1939 and the guarantee to Poland which eventually led to Britain's declaration of war on Germany on 2 September 1939.

For the second time in a quarter of a century, therefore, Britain was involved in total war (Chapter 11). Unlike the First World War, Britain's military role was largely on the periphery—in North Africa and Italy, at sea, and in the air. Britain was the combatant which kept the war going long enough for the Soviet Union and the United States to become involved and finish Germany off. During the whole process, Winston Churchill provided highly effective leadership, although his precise role has been subject to some reinterpretation. In political terms, Britain established an authoritarian government much more quickly in the Second World War than in the First, although full democracy returned rapidly in 1945. There is no doubt that the war benefited Labour much more than the Conservatives, healing their rift of the 1930s, while it all but finished off the Liberals. Economically, the war continued the process of British decline, while socially there were more consequences than after the First World War. This was canalised in the Beveridge Report of 1942, which provided the theoretical foundations of the modern welfare state and especially the National Health Service. The precise extent to which such changes were due to the war, is, however, debatable.

Even before the end of the Second World War a general election was held in Britain which swept Churchill out of office and gave Labour a huge overall majority—its first ever (Chapter 12). At the time this result came as a major shock, but most historians argue that it should not have done—that it was the result of Britain being radicalised by the experience of war and by the increased expectations of social reform, which Labour was considered most likely to deliver. The changes made by the 1945–51 Labour government were fundamental. They included the welfare state, with its integral national health service, and the nationalisation of a number of key industries and enterprises. These have been considered a radical break with the past and the introduction of a new type of state with more centralised governmental controls. But was this true? It could also be argued that the changes which emerged after 1945 had their roots very much in the periods 1905–14, 1914–18 and 1918–39, as well as in the second experience of total war.

After establishing the welfare state, Labour gave way to the Conservatives (Chapter 13), who won three general elections in a row in 1951, 1955 and 1959. The Conservatives retained most of the reforms which had been introduced by the Attlee government, deciding only to renationalise the steel industry. The length of their tenure of office was due partly to the effectiveness of ministers like Butler, Maudling, Macleod, Macmillan and Heath and partly to a series of favourable objective factors.

These included a period of economic growth which the Conservatives claimed as their doing, an assertion which is examined. They also benefited from Labour's internal divisions between the left, who wanted to press on with the destruction of the capitalist system and the abandonment of nuclear weapons, and the right, led by Gaitskell. The decline of the Conservatives was due to the reversal of the earlier factors which had operated in their favour. After 1960 the economy took a downturn and had serious political effects with which Macmillan could not cope. The Conservatives also faced a series of scandals, to which most ailing governments seem to be prone. Meanwhile, Labour had recovered its unity with the reconciliation of the left and right under the pragmatic leadership of Harold Wilson. This enabled him to win a narrow majority in the 1964 general election, which he substantially increased the following year.

The period 1964–79 saw a full return to two-party politics: Labour under Wilson dominated the period 1964–70, the Conservatives under Heath were in power between 1970 and 1974, and Labour returned between 1974 and 1979, initially under Wilson, who was succeeded by Callaghan. It was a period of crisis and reforms (Chapter 14). The latter saw an attempt to deal with a wide range of issues which had been shelved by the Conservatives between 1951 and 1964. Reforms affected the civil service and other areas of the administration, local government, moves towards devolution for Scotland and Wales, changes in the House of Commons committee system, attempts to modernise the House of Lords, enlargement of the electorate by reducing the voting age to 18, and a wide range of bills covering social issues including the death penalty, sexual offences, divorce, race relations, sex discrimination, industrial relations. Crisis affected mainly the economy, with balance of payments deficits, inflation and industrial disruption on a scale unknown since the 1920s. This accelerated during the 1970s. Heath attempted to move towards government de-control, but failed. The crisis in industrial relations had a profound political impact, helping more than anything else to bring down Heath in February 1974 and Callaghan 1979.

The election of 1979 was to prove one of the most significant of the twentieth century. It brought to power a prime minister who was determined to reverse the previous consensus that had existed between Labour and the Conservatives about the broad stream of economic and social policy (Chapter 15). She was committed to reducing the role of government, although ironically this meant the actual extension of its powers. She based her economic policies upon the principles of monetarism, she introduced the notion of privatisation and restructured central and local government. She was able to do all this as a result of three successive election victories in 1979, 1983 and 1987. In these she was assisted partly by external factors, such as the Falklands War of 1982 which diverted public opinion from the unpopularity of her earlier policies, and partly because of the divisions within Labour. Overall, some observers have advanced the claim that there was a ‘Thatcher revolution’, although it could be asked whether her policies were primarily ideological or opportunist.

Meanwhile, the Conservatives were given an extended lease on power by the second crisis to have affected the Labour party (Chapter 16). Following their defeat in the 1979 general election, Labour experienced a substantial swing to the left, which gave the leadership to Michael Foot and caused the withdrawal of the right to form the new Social Democratic Party (SDP). Labour's policies also moved leftwards, including a commitment to unilateral nuclear disarmament. The party was, however, severely embarrassed by the activities of its far-left Trotskyist fringe and by the massive erosion of support from the sectors of the population who traditionally supported it. The loss of four consecutive general elections forced a review of both the organisation and policy of the Labour party. This was undertaken by Kinnock, Smith and Blair, who moved the party steadily back towards the centre ground and adopted a more pragmatic approach in the tradition of Gaitskell and Wilson. Although Labour lost the 1992 general election, their recovery was well under way and by 1995 they seemed well placed to win the next election.

Returning to 1945, another strand in Britain's post-war history was her foreign policy (Chapter 17). Britain emerged from the Second World War convinced that she could continue her role as one of the superpowers. This was largely because of her role, along with the United States and the Soviet Union, in defeating Nazi Germany. During the 1940s Britain too...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- 1: INTRODUCTION TO BRITISH POLITICAL HISTORY 1914–95

- 2: THE FIRST WORLD WAR AND ITS IMPACT

- 3: THE DECLINE OF THE LIBERAL PARTY 1914–40

- 4: THE 1924 LABOUR GOVERNMENT

- 5: BALDWIN AND THE CONSERVATIVE ASCENDANCY BETWEEN THE WARS

- 6: THE GENERAL STRIKE

- 7: THE FIRST CRISIS OF LABOUR 1929– 39

- 8: THE ECONOMY, UNEMPLOYMENT AND GOVERNMENT POLICY BETWEEN THE WARS

- 9: VERSAILLES, FOREIGN POLICY AND COLLECTIVE SECURITY 1918–33

- 10: FOREIGN POLICY AND APPEASEMENT 1933–9

- 11: THE SECOND WORLD WAR AND ITS IMPACT

- 12: THE LABOUR GOVERNMENT 1945–51

- 13: THE CONSERVATIVE DECADE Domestic Policies 1951–64

- 14: YEARS OF REFORM AND CRISIS 1964–79

- 15: THATCHERISM AND AFTER, 1979– 95

- 16: THE SECOND CRISIS OF LABOUR 1979–92

- 17: FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENCE 1945–70

- 18: FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENCE 1970–95

- 19: BRITAIN AND EUROPE SINCE 1945

- 20: THE BRITISH EMPIRE AND COMMONWEALTH IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

- 21: THE IRISH ISSUE 1914–96

- 22: EQUAL OPPORTUNITIES AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY BRITAIN

- 23: IMMIGRATION, RACE RELATIONS AND THE PLURAL SOCIETY

- 24: PRIMARY SOURCES FOR BRITISH POLITICAL HISTORY 1914–95

- NOTES

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY