CHAPTER 1

Public spaces for a changing public life

Jan Gehl

Introduction

Recent decades have seen a gradual development from industrial society’s necessary public life to the optional public life of a leisure and consumer society. Where city life was once a necessity and taken for granted, today it is to a high degree optional. For that very reason, this period has also seen a transition from a time when the quality of city space did not play much of a role in its use, to a new situation in which quality is a crucial parameter. In the past, people had to use the streets and squares of the city regardless of their condition. Today this is in the majority of cases an option.

It should, at this point, be noted that the changes described in this chapter relate to societies where the economic developments have initiated a shift towards leisure and consumeroriented lifestyles. In many less developed regions in the world, life in public spaces typically has not changed materially to such a degree and is still found to be very much dominated by necessary activities.

The traditional city: meeting, market and moving

Seen in a long-term historical perspective, city space has always served three vital functions – meeting place, marketplace and connection space. As a meeting place, the city was the scene for exchange of social information of all kinds. As a marketplace, the city spaces served as venues for exchange of goods and services. And finally, the city streets provided access to and connections between all the functions of the city (Gehl and Gemzøe, 2001).

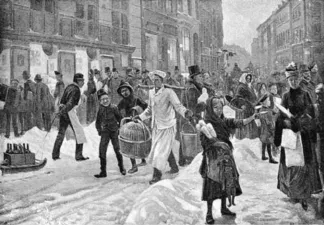

This pattern can be followed from the earliest urban settlements through Greek and Roman cities, medieval cities, renaissance and baroque cities as well as cities from the age of enlightenment and the industrial age. City spaces have teemed with people and functions throughout history. Life in city space was an integral and utterly essential part of society. Numerous descriptions, paintings and engravings from various periods in history, as well as pictures from the early days of photography, vividly tell this story.

In the medium term, referring to situations just a hundred years ago, the patterns continued, as seen in photographs and street scene engravings from around 1900. City spaces functioned as meeting place, marketplace and connection space. The streets were crowded with people burdened with goods and packages or simply on their way by foot through the city, a testimony to a time when few other forms of transport were available. Goods were sold from booths or by street peddlers. Numerous people of all ages were on the streets and squares to take part in city life or simply because there was not enough room inside their crowded dwellings, small shops and cramped workshops. It is clear from old pictures that public city life was completely dominated by the activities essential to everyday existence.

Twentieth century: a near farewell to public life

In the course of the twentieth century a number of important developments have taken place in cities such as Copenhagen. First and foremost, these hundred years have seen a dramatic improvement in the economic conditions of the city and its dwellers. This development accelerated, especially in the second part of the century. The growth in the economy led to a wide range of changes in society situation and in lifestyles. Two developments, derived from the changes in economic conditions, have had a particularly dramatic influence on the concept of public spaces as well as on their physical appearance and the conditions for public life.

1.1 1880. Old engraving showing city life on Strøget, Copenhagen’s main street, a century ago. Essential, work-related errands dominate.

The Modern Movement, from the mid 1920s onwards, in its quest to provide growing urban populations with cleaner and healthier cities and accommodations, dramatically downgraded the importance of traditional public spaces. Streets and squares were declared unhealthy and unwanted, and activities in such places were severely criticized as being shady, unbeneficial and, to a wide extent, amoral. Parkland settings for housing, with trees and lawns as meeting places instead of streets and squares, would be the new answer to the calamities of the traditional townscapes. The CIAM Athens charter of city planning (1933) laid down the new rules and stated that residences, work, recreation and transport should be strictly separated in the modern city. This dramatic ideological condemnation of traditional forms of public space and public life would, for several decades, effectively stop any development of the townscape as well as research and discussions concerning public life.

The other dramatic development, which drastically changed the conditions for cities, public spaces and public life in the twentieth century, was the influx of motor cars in great numbers. The car invasion had been going on at a moderate rate since the beginning of the century, but really took off in the mid 1950s, some ten years after the Second World War.

Thus, by the early 1960s, a situation had developed where new Modernistic planning concepts had more or less phased public life out of the new city districts, while in all the older parts of the cities, what remained of public life was harassed or simply squeezed out of streets and squares by traffic and parking.

Early 1960s: a turning point

The book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961 by Jane Jacobs, marked a turning point in the gradual erosion of the concept of public spaces and public life. From around this time it is possible to see a number of related events – the closing of streets to traffic, the introduction of pedestrian streets, as well as a growing amount of research and publications promoting the concept of public spaces and public life. This ‘Public Life oriented wave’ in urban research and urban planning (Gehl, 1971, 2006) has now been around for some forty years, gaining momentum all the way along.

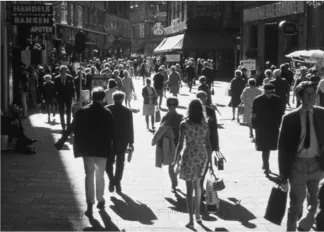

1.2 c.1960. Strøget invaded by cars. City life is forced onto narrow pavements with room for only the most essential pedestrian activities.

Europe’s first major wave of pedestrian streets dating from the 1960s were primarily introduced to provide better conditions for customers in the commercial centre of the city. The streets were conceived as shopping streets, and pedestrianisation was seen as an urban response to the new suburban shopping malls that allowed people to shop without interference from traffic. Shopping bags dominated the city centres in the 1960s and 1970s, and the main activity was walking between the shops. At this first stage the streets truly were walking streets (Gehl, 1971, 2006).

The Danish capital, Copenhagen, serves as starting point and case study for this account concerning the dramatic changes in public life. For the past 40 years, researchers from the School of Architecture at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts have systematically recorded the development and changes in the life and spaces of the city. Major studies have been conducted, in 1968, 1985, 1995 and 2005, making Copenhagen the first city in the world where the development of city life has been followed and documented over several decades (Gehl and Gemzøe, 1996; Gehl et al., 2006).

1.3 1968. Strøget five years after conversion to a pedestrian promenade. Car-free streets are seen as the antidote to suburban shopping centres.

Case story: Copenhagen

The comprehensive surveys carried out in Copenhagen can be seen as part of this greater movement towards securing a renaissance for public space and public life in the culture of European cities (Gehl and Gemzøe, 1996). The Copenhagen studies were inspired by the introduction of Strøget, the main street of Copenhagen, as one of the first major pedestrian conversions in Europe. Strøget was closed to car traffic in November 1962 and by 1968 the new use of the street had stabilized and lent itself to investigations. What kind of life would be going on in such a traffic-free environment? And how were the other public spaces of the city used at this point? These were some simple research questions from the very first surveys, but the data thus gathered has made it possible to return regularly over the following forty years, in order to see how the spaces and the public life have developed. It is in this context that the dramatic changes in the character of public life have been recorded.

New and much more diversified activity patterns soon began to emerge towards the end of the 1960s and through the 1970s. The first outdoor cafés arrived, and the student revolution and ‘flower power’ movement brought people into the streets for political and cultural happenings. The trend was reinforced gradually as car parking was eliminated from the city squares and there was more room for city life. Soon city space was used for more political and cultural events, as well as quiet recreation and enjoyment. The number of cafés with outdoor service and the sheer number of café chairs in the city centre of Copenhagen has, during the four decades studied, almost exploded, from 3,000 in 1985 to 5,000 in 1995 and 7,000 in 2006. This development has been accompanied by an impressive extension of the outdoor season. Thirty years ago, the outdoor season in Copenhagen lasted two summer months, but it has now gradually been extended to cover almost the entire year. The café chairs now come out in early March and only go in after the closure of the equally new phenomena – the Christmas Markets. In general, changes in the pattern of using city space have been far-reaching. A century ago, activities were almost exclusively sively necessary, forty years ago the primary focus was shopping, while recent decades have added a host of recreational activities and more cultural events, parades, happenings and exhibitions. Most recent is the wave of sport and exercise in public spaces.

1.4 2005. Strøget, now a mixed staying and walking street.

Recreation and cultural activities play an increasingly greater role in the city scene.

The general feature of these changes is that, within the span of only a few decades, a work-oriented cityscape has become a city of leisure and enjoyment. Of course, the picture is not quite that simple, because working and shopping are obviously still going on, but now in parallel with urban recreation and many other pastimes. Another trend is that outdoor recreation and enjoyment are, as might be expected, predominantly a summer phenomenon, heavily dependent on the quality of city spaces as mentioned earlier, while winter city life continues to be more dominated by work-related activities and shopping. A distinct, two-season culture has evolved.

When people were interviewed in the 1970s and 1980s, their primary reason for being in the city centre was: ‘shopping’. The same question asked in 2005 was more likely to generate the response: ‘to be in the city’. By 2005 the city had definitely become a goal in itself, a destination in its own right. The growing trend of moving residences back to the city centres generally tells the same story (Gehl et al., 2006).

The new city life

Looking generally at the development of city life in Copenhagen over the past forty years, we see it undergoing a dramatic development after many years of languishing under pressure from car traffic. More people use the city and spend more time there, and we can see city life growing year by year. The days are longer as city life is expanded to include evening hours on days with good weather. The week is longer with more activities on Saturday and, most recently, Sunday as well. And, finally, as mentioned above, the outdoor season has been extended appreciably (Gehl et al., 2006).

The dramatic development in indirect digital communication has led to many predictions that public space will soon be replaced by cyberspace. The surveys from Copenhagen and many other cities, notably the recently published evidence of increase in city life in Melbourne (City of Melbourne and GEHL Architects, 2004) certainly do not support this theory. During the years in which the new electronic options have burgeoned, city life has been markedly strengthened. The multiplicity of electronic pictures and messages would appear not to detract from public life but rather to provide extra inspiration to ‘be present in person’ and ‘see things with your own eyes’.

From Canada in the west to Japan in the east, and from Australia in the south to Scandinavia in the north, street-side cafés are increasingly more numerous in the city scene. The users of city space are frequenting cafés by the thousands. A hundred years ago, people went to the city because they had things to do and were forced to go, and while they were there they had many opportunities to look at life and meet fellow citizens. Today, where staying in the city is a choice, people need activities to keep them appropriately occupied for hours without attracting unwanted attention. Here, the cappuccino culture has acquired an important role as an excuse or rational explanation for the many lengthy stays in town. Both then and now, the meeting between people is a key city function, but people now use new formal explanations for spending time in the city. This is exactly where the cappuccino has come in handy.

1.5 From necessary to optional activities. Development of public life from 1880 to 2005.

A graphic illustration of the dramatic changes in the character of city life during the twentieth century. Essential work-related activities dominate around 1900. The streets are crowded with people, most of whom have to use city space for their daily activities. The picture has changed appreciably by the year 2000. Essential activities play only a limited role because the exchange of goods, news and transport has moved indoors. In contrast, elective recreational activities have grown exponentially. Where the city once provided a framework almost exclusively for work-related daily life, the city hums with leisure- and consumer-related activities in 2000. Recreational activities set high standards for the quality of city space, and can be roughly divided into two categories: 1) passive staying activities such as stopping to watch city life from a stair step, a bench or a café, and 2) active, sporty activities such as jogging and skating. The timeline also shows when the car invasion hit Denmark in the mid 1950s. The pressure of car traffic and functional planning in the 1960s triggered a counter-reaction to reclaim city space. In the following forty years this reaction was reinforced, and developed nationally and internationally in an ongoing process.

Dramatic changes in living standards, working life and the economy have contributed in various ways to the new f...