eBook - ePub

Feminist Review

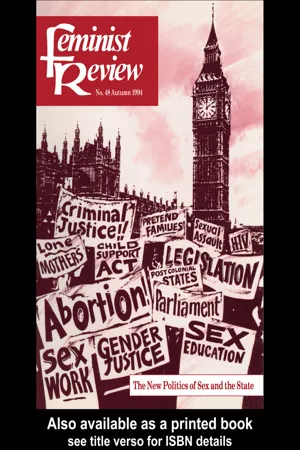

Issue 48: The New Politics of Sex and the State

This is a test

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A unique combination of the activist and the academic, Feminist Review has an acclaimed place within women's studies courses and the women's movement.

Feminist Review is produced by a London-based editorial collective and publishes and reviews work by women; featuring articles on feminist theory, race, class and sexuality, women's history, cultural studies, Black and Third World feminism, poetry, photography, letters and much more. Feminist Review is available both on subscription and from bookstores.

For a Free Sample Copy or further subscription details please contact Trevina Johnson, Routledge Subscriptions, ITPS Ltd., Cheriton House, North Way, Andover SP10 5BE, UK.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Feminist Review by The Feminist Review Collective in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminism & Feminist Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Out of the Shadows: Women, Resistance and Politics in South America

Jo Fisher

Latin American Bureau: London 1993

ISBN 0 906156 77 7 £7.99 Pbk

Out of the Shadows, Jo Fisher’s book on women and politics in South America, is a testament to South American women’s tenacity in the face of severe hardship and oppression. It is the latest of the excellent series of publications by the Latin American Bureau on contemporary issues in South and Central America. The author spent two years researching the book, travelling in Uruguay, Paraguay, Argentina and Chile. The political women of the region have radicalized the traditional roles assigned to women by societies in which machismo is still a dominant ideology. They turned the roles associated with nurturing and home-making around and literally brought them out into the streets. In this way, they have given a very public, collective voice to their private, individual sorrows. This exemplifies the process described by bell hooks: ‘Speaking becomes both a way to engage in active self-transformation and a rite of passage where one moves from being object to being subject. Only as subjects can we speak. As objects we remain voiceless—our beings defined and interpreted by others’ (hooks, 1989:63).

Maxine Molyneux, in her discussion of the Nicaraguan revolution and women’s interests, differentiates between two types of women’s interests—strategic gender interests and practical gender interests. The former is a deductive scheme in which ‘ethical and theoretical criteria assist in the formulation of strategic objectives to overcome women’s subordination’ (1985:232–3). The social actors in this case are highly politically aware individuals. In the latter type of political action, the everyday realities come first and the achievement of particular strategic goals are not really a priority. The types of action in Fisher’s book usually fall into the latter category. She documents forms of activity initiated by the women themselves, those who are directly involved, designed to improve conditions in the ‘here-and-now’. Consequently, the worse the conditions, the more likely it is that action will take place. The question as to why strategic gender interests do not usually inform South American women’s political action may indicate that these astute women’s perception of feminist theory may not be the most positive.

Fisher documents the negative image that the political women of South America had about Western feminism and feminists. Her interviewees believed that these were culture- and class-bound in their analysis of women’s issues. This is a product of the dominant image of Western feminism as white, North American and middle class. The dominant stream within North American feminism is based on a very individualistic model, with the collective basis of feminist thought being pushed to the background. South American women in general cannot relate to this mode of thinking because for them, the empowerment of the whole community comes first. Thomson (1986) found that women in El Salvador distrusted Western feminism because it contradicted their Catholic, often conservative views on the family and women’s roles. Also, the pronatalism of the male revolutionary rhetoric led Salvadorean women to aspire to producing more ‘sons for the revolution’. This also indicates lack of interaction and debate between feminists of different national and political backgrounds. Feminism of the 1980s and early 1990s has witnessed the expression of new concerns, particularly by non-Western feminists. These concerns are those of differences between women in the world, assumptions of a common global agenda and potential ‘colonization’ of one group of feminists by another (see Mohanty, 1984). It is clear that there exists a need for the clear articulation and appreciation of local and regional identities within feminist thinking. I believe that it is a testament to the openness of the women’s movement that these issues are addressed at all, and that potential problems and divisions are not ignored, as in some other contemporary social movements.

The example of one particular group, the ‘Mothers of the Disappeared’, is indeed an inspiring one. The amazing courage demonstrated by this group was a force too strong even for the brutal armies of Pinochet and other military dic tators. This group began in Chile in the 1970s but spread right throughout South and Central America. Groups of women whose husbands, partners and sons had been ‘disappeared’ by the army engaged in very dangerous public political activity, despite the ‘disappearance’ of some of their leaders by the authorities. They thus instigated and institutionalized a form of political organization that was initially perceived by the public as ‘soft’ and unthreatening. However, they were actually responsible, perhaps more than any other group, for the raising of awareness internationally about repression in South and Central America. Another effect of women’s autonomous organization in South America and the resulting rising tide of articulate voices was the realization by many women that many of the international organizations that were meant to be progressive were instead very male-dominated and did not serve the interests of women. Thus their own initiatives enabled them to criticize the actions of others.

Another example of an apparently benign but actually very subversive activity which is discussed by Fisher was the production and sale of ‘arpilleras’, the tapestries which documented the women’s lives and forms of political action. They became instruments for spreading knowledge internationally and, consequently, their distribution was prohibited by the authorities. The ‘arpilleras’, above all, demonstrated the very real power of symbols. The depictions of apparently mundane everyday activities like shopping, sewing and cooking were a very touching reminder of the disruption of ordinary people’s lives by political repression. Another example of this symbolic power is the liaison between a women’s folk group from Chile with the Amnesty International tour in which Sting, among others, participated. This folk group performed a Chilean folk dance and one of the women danced on stage alone, effectively evoking the loneliness of their lives without their ‘disappeared’ partners.

This book shows that, when the state does not provide for the people, the burden falls upon women to maintain the community. Moser (1992), in her research in Ecuador, found this to be the case and deemed that women exercised a ‘triple role’—that of homemakers, workers in the workplace and participants in community politics. As this process continues, however, women’s increased articulation of their needs and their visibility in the public domain begins to perpetuate itself, thus enabling new definitions of what is appropriate behaviour for women to emerge. The book is also a testament to the diversity of women’s experience and necessary political strategies, from the communal kitchens and Mothers of the Disappeared in Chile to the struggle to include women’s concerns in Uruguay’s trade union movement and Paraguay’s peasant movement.

South America’s women’s movement has very effectively challenged the patriarchal nature of formal politics, both left and right, and has literally ‘given a voice’ to some of the most oppressed members of South American society. A challenge for the future is how to forge unity and solidarity among the many groups in question, in order to build an even stronger movement from the diverse groups documented in this important and invigorating book. South American women and feminists can reach out beyond their local worlds to others’ local worlds and feminists can then, in this way, reach a new definition of the ‘local’ and forge global links on the anvil of diversity.

Ethel Crowley

References

CAIPORA WOMEN’s GROUP (1993) Women in Brazil London: Latin American Bureau.

hooks, bell (1989) Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black London: Sheba Feminist Publishers.

Mohanty, c. T. (1984) ‘Under Western eyes: feminist scholarship and colonial discourses’ Boundary Vol. 2, No. 12: 333–358.

Molyneux, M. (1985) ‘Mobilization without emancipation? Women’s interests, the state and revolution in Nicaragua’ Feminist Studies Vol.11, No.2, Summer: 227–254.

Moser, c. (1992) ‘Adjustment policies from below: low-income women, time and triple role in Guayaquil, Ecuador’ in Afshar, H. and Dennis, C. editors, Women and Adjustment Policies in the Third World Basingstoke; Macmillan: 87–116.

Accommodating Protest: Working Women, the New w Veiling and Change in Cairo

Arlene Elowe Macleod

Columbia University Press: New York 1991

ISBN 0 231 07281 3 £9.50 Pbk

The aftermath of the 1967 and 1973 wars with Israel created a propitious environment for a new movement, voluntarily initiated by women: it is the veiling movement. By the early 1980s it became an overwhelming fact of life, almost the norm on Cairo streets. According to Macleod, the veiling was spurred largely by Islamic groups in universities, but later gained considerable appeal and was adopted by a broader spectrum of women. This veiling has raised many questions as to its symbolism and implications: if the veil is a symbolic action, what exactly does it symbolize? Are women supporting a return to traditional patterns of inequality by reviving this ‘powerful symbol of women’s subordination’? Macleod attempts to answer these questions by venturing into very thorny areas. She studies how class interacts with gender, and notes that the problems women face in Egypt are also problems of poverty and not purely of gender inequity. The Cairenne society is a society where people are acutely class conscious, and have a ‘strong sense both of hierarchy and of their place in this social and economic ranking system’. It is also a society where, in the midst of modernization and commercialism which result in confusion as well as the loss of the sense of identity, there is an increased interest in praying, and in the return to God, in the hope of a better future. But the problem is that theological debates and interpretations are impregnated with state politics which consecrate women’s inferior position in the hierarchy.

Macleod’s findings are the result of a five-year study in which she interviewed Egyptian women from the lower-middle-class stratum. The book discusses the dilemma of women in the midst of the turmoil of a changing Cairo: women leaving their traditionally accepted roles of mothers and wives as they are pushed into the workforce through economic pressure. Tragically, these women are not looked upon as dignified workers, but are rather blamed for leaving their homes and abandoning their ‘traditional’ images and identity. So how do these women react?

Despite the existence of a feminist movement in Egypt, feminism as an ideology has not reached these classes. Thus while society’s changes force these women to join the workforce, the gender ideology remains static, continuing to demand that a woman’s place is at home. As the author suggests, ‘the economic ethos and gender requirements clash’, placing women in an impasse. The higab, in such a context, serves as a moderate resolution to women’s con flicts and dilemmas. It is a statement which creates a ‘new self-image, offering in symbolic fashion a partial resolution of the pressures women experience at the intersection of competing subcultural ideologies’.

Cairo’s lower-middle-class women do not work for the intrinsic value of work; Macleod rightly observes that this value is an upperclass prerogative. These women fund their family’s basic needs from their earnings, and their entrance into the workforce is not a choice made for self-development or bliss, but a ‘hard fact of life’. Unlike Western women, they do not attempt to seek individualistic emancipation, autonomy and self-sufficiency, but are rather attempting to focus on fulfilling basic family needs. Nevertheless, work offers these women a considerable amount of security and mobility which is otherwise denied them. Disenchanted with the economic and moral power of their work, they therefore look forward to the day when they leave it, without losing the gains they have acquired, basically mobility.

Macleod asserts that Egyptian women are not, as the West perceives, Victims of an oppressive cultural milieu with its ultimate symbol the veil’, but rather, they are strong and confident in their behaviour, ‘resourceful in manipulating their situation’: they struggle, but it is their special mode of struggle. The veil, according to Macleod, is political protest with the only means available to these women: it is not a stereotypical revolt, but rather a struggle which involves an ‘ambivalent mixture of both resistance and acquiescence, protest and accommodation’.

One very important observation the author makes is that the movement is not a return to the veil, but rather a new veiling—one which represents a part of an ambiguous political struggle she appropriately terms ‘accommodating protest’. The new veil is a sort of fashion statement as well as a ‘values’ statement. It is a selective return to roots and to a set of values which women feel the need to re-emphasize, and it serves to resolve women’s inner conflict. Women who take to the veil, therefore, do not attempt to challenge their previous roles as mothers and wives, and work does not form a disruption from their main duties or an infringement of their values. Rather, the veil emboldens them, and emphasizes their austerity, functioning as a ‘bridge, an alleviation, a kind of balance for these women, compensating for their otherwise inappropriate behaviour’, whether this ‘inappropriateness’ is education or work. Women, therefore, have made a statement about their ability to work, and still feel proper Muslim women: they ‘feel more at peace with society, their reputation becomes more secure, and their freedom of movement remains assured’.

There is one major problem which Macleod points out: these women, in their attempts to accommodate, are selective in their return to roots and in their approach to cultural values. But this return will be taken up by others without such selection, eventually subduing the protest, while emphasizing accommodation only. Such resistance then is accompanied by acquiescence. It is an acquiescence that may eventually run amok by ‘inadvertently strengthening the inequalities they would like to escape’.

Marlyn Tadros

Subject to Others: British Women Writers and Colonial Slavery 1670–1834

Moira Ferguson, Routledge: New York/London 1992

ISBN 0 415 90476 5 $19.95/£12.99 Pbk

ISBN 0 415 90475 7 $55/£40 Hbk

Women Against Slavery: The British Campaigns 1780–1870

Clare Midgley

Routledge: New York/London 1992

ISBN 0 415 06669 7, $69.95/£37.50 Hbk

In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick—a Leicester-born Quaker and ‘the foremost female anti-slavery pamphleteer’ of her generation— argued that ‘slavery is not an abstract question, to be settled between the Government and the Planters—it is a question in which we are all implicated’. Heyrick’s words signal her keen awareness that white British women were not exempt from the moral consequences of colonial slavery. It was precisely this sense of personal moral obligation which she believed legitimated those claims to action in the public sphere made by mostly middle-class anti-slavery women on behalf of slaves. Her biography, together with those of Mary Prince and other Black women enslaved in the name of ‘civilization’, is crucial for understanding the uses to which white women put both the metaphor of bondage and the material realities of black slavery in order to forge a national political identity for themselves in pre- and early Victorian Britain. As both of these studies make clear, without Black women’s own persistent quest for liberty, white women’s philanthropy and indeed their early identification with Britain’s ‘civilizing mission’ would have had an almost unimaginably different justification. What Midgley and Ferguson together require, then, is that we not simply re-materialize women’s historical contributions to antislavery, but also critically examine what Ann Curthoys calls our presumption of women’s ‘historical innocence’ (Curthoys, 1993:174).

In the broadest sense these books address the mainstream historical establishment, which has either neglected or marginalized women’s role—black and white—in the abolition of slavery. To borrow bell hooks’s term, they also ‘talk back’ (hooks, 1990:207–11) to established historians of women and of feminism who have been insufficiently attentive to the historical intersections of race and gender politics in the West and, until recently, particularly in Britain. Vulnerable to appeals about the un-Christian nature of slavery because of the ways in which evangelical discourse positioned them, bourgeois white women throughout Georgian Britain took up the cause of men and particularly of women slaves with tremendous fervour. They set up their own anti-slavery societies through which they carried on a wide range of activities related to the anti-slavery project, including boycotting sugar; petitioning Parliament over slavery and the apprenticeship system; producing ‘physical propaganda’ like workbags to sell for the cause; and writing, writing, writing—pamphlets, plays, poetry, speeches, cheap repository tracts. Slavery was undoubtedly one of the chief idioms through which white women’s political, cultural and national identities were articulated in this period, with Black men and women serving as the ‘subjects’ through whom they claimed their own socio-political subjectivities. That white women in Britain saw this as natural, unproblematic and foundational to their own quest for legitimating work in the public sphere is borne out in all of their ideological productions. One of the constitutive effects of white wo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Contents

- Editorial: The New Politics of Sex and the State

- Not Just (Any) Body Can be a Citizen: The Politics of Law, Sexuality and Postcoloniality in Trinidad and Tobago and the Bahamas

- State, Family and Personal Responsibility: The Changing Balance for Lone Mothers in the United Kingdom

- Moral Rhetoric and Public Health Pragmatism: The Recent Politics of Sex Education

- Through the Parliamentary Looking Glass: ‘Real’ and ‘Pretend’ Families in Contemporary British Politics

- In Search of Gender Justice: Sexual Assault and the Criminal Justice System

- God’s Bullies: Attacks on Abortion

- Sex Work, HIV and the State: An Interview with Nel Druce

- Reviews

- Noticeboard