- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

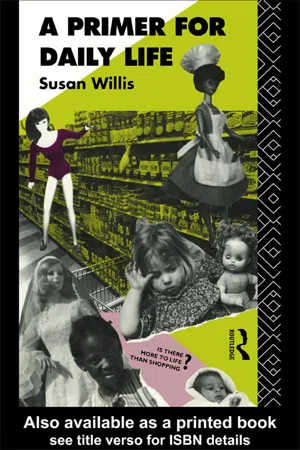

A Primer For Daily Life

About this book

The interacting components of everyday life - the weekly supermarket shopping trip, fast food, children's toys - are still largely unremarked by cultural theorists. Grounded in Marxist theory, and guided by feminism, Susan Willis's lucid and entertaining study of the consumer culture broadens the scope of cultural studies to introduce the notion of daily life, with the commodity at its centre. Willis pays particular attention to the influence of commodity fetishism on social relations. Her investigation includes the taken for granted phenomena of modern culture - Barbie dolls, plastic packaging, banana sticker logos and the aerobic workout.A Primer For Daily Life demonstrates that the trivial is crucial for our understanding of capitalist culture, and argues for the necessary development of a critical perspective on daily life.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

UNWRAPPING USE VALUE

Everything is packaged. Late twentieth-century commodity production has generated a companion production of commodity packaging that is so much a part of the commodity form itself as to be one of the most unremarked features of daily life. Only when we have to drag all those 30 gallon black plastic trash bags out to the curb or haul them to the town dump are we likely to grasp the enormity of packaging. Otherwise, it goes unnoticed even in drug stores and discount department stores where fully 80 per cent of the merchandise is packaged. Whether items are individually boxed or mounted for display on strips of cardboard backing, most packaging today includes a plastic see-through window or bubble. Packaging catches the consumer's eye, even though as a phenomenon of daily life, it is all but invisible. The package is a device for hailing the consumer and cueing his or her attention, by the use of color and design, to a particular brand-name commodity. The plastic cover replicates the display case or store window and suggests that each and every item is worthy of display.

Packaging also enables the standardization of weights and measures. For today's consumer, the “net weight” label is the only guarantee that a box of laundry detergent indeed weighs 4 lb or that the peanut butter in a particular jar really does amount to l lb 2 oz. The standardization of weights and measures represents a rationalization of sales similar to the Taylorization of production. In the workplace, Taylorization increased efficiency and productivity because in breaking production down into rationalized units, it offered the owners of the means of production greater control over the production process and a more systematic exploitation of the workforce. Taylorization has its end in the consumption of rationalized commodity units. Many of the basic foodstuff items that fill our kitchen cupboards today, such as crackers, cereal, flour, and pickles, were originally sold in bulk. Richard Ohmann describes the moment when Quaker Oats were first available as a packaged commodity, and develops the relationship between early instances of mass commodity packaging in the late nineteenth century and the expansion of the professional class, the first class in this country to function en masse as consumers (Ohmann, 1988). By comparison with commodities previously sold in bulk, mass-produced and packaged commodities, like Quaker Oats in the original 2lb package, were advertised as a more efficient means to buy and store basic household necessities. While it is true that increased urbanization from the 1890s on meant that more and more families did not have storage space for bulk merchandise, the underlying effect of mass commodity packaging is to break sales down into standardized units, thus enabling commodity producers to have greater control over consumption and a more systematic means of exploiting the consumer through advertising. Prior to the 1890s, there was no advertising for what would later become Quaker Oats, because, if such advertising had existed, it could only have promoted oats in general. The point of advertising is the designation of the commodity (and, by extension, the consumer) as a discrete unit.

The immensely popular advertising campaign devised for marketing California raisins suggests a new conceptualization of the commodity in keeping with postmodern capitalism. Where raisins from California were once marketed according to specific brand-name identities such as “Sun Maid,” they are now promoted as the “California Raisins” and embodied in a band of wrinkly faced black “dudes” with skinny arms and legs, who chant “I Heard it Through the Grapevine” while soaking up the California sun. “California Raisins” do not represent a return to the pre-brand-name generic commodity, but rather the hyper-commodity whose connection to rock music and black culture heroes precipitates a vast array of spin-off products, from grotesque dolls to beach towels emblazoned with the “Raisins.” If brand-name marketing represents the Taylorization of consumers, mass-marketing spin-off advertising is the postmodern form. Rather than fragmenting the broad mass of consumers into discrete and manageable units, postmodern advertising assumes a consuming subject capable of being interpolated from a number of angles at once. We will consume the “California Raisins” even if we never eat dried fruit.

Another significant function of packaging is to promote the notion of product purity. When Henry P.Crowell first packaged oats, he marketed them as “pure” by comparison with oats sold in bins and exposed to the air as well as the hands and coughs of salespersons. In late twentieth-century consumer culture, hygiene has complex ideological associations, most of which derive from the notion of progress which makes a primary distinction between the developed societies of the First World and the underdeveloped societies of the Third World. Purity is synonymous with the modern First World supermarket, where items are discretely shelved; bruised fruit, greying meat, and milk past its freshness date are removed; and where everything is enveloped in air-conditioning—yet another form of packaging whose frigid, artificial air exudes the very notion of purity. After all, germs cannot survive freezing temperatures; and in the First World, purity means being germ-free, even if the elimination of microbes requires heavy doses of pesticides, chemical preservatives, fumigation, radiation, and other artificial stratagems. To the First World imagination, the open-air markets of the Third World are a riot of impurities. The aromas of ripe fruits, meats, and cheeses cannot be conceptualized without the consequent horror of bacteria. Foods brimming over in baskets or loosely arranged on counters, in bins, or on the pavement suggest an indiscrete mingling of merchandise—and worse yet, people. In the First World, the package is the fetishized sign of the desire for purity, which, in the fullest sense, is also a desire for security. The ultimate outrage in commodity capitalism is product adulteration. Haunting the desire for purity are the tales told of food-service workers who, when angry or bored, spit, even urinate, into the not yet frozen or sealed TV dinners. Similarly, the consumer's desire for security meets its most chilling nightmare in the case of the deranged product tamperer, for whom the security seal on a bottle of Tylenol is a challenge to cyanide.

These functions of packaging and their ideological implications demonstrate that the throwaways of commodity consumption may well offer the most fruitful way into the culture as a whole. While the foregoing themes may well be complex and interesting, none, however, really scrutinizes packaging as a dimension of the commodity form itself. Such an analysis would look at packaging as a metaphor for the formal economic contradiction of the commodity. In Capital, Marx initiated his analysis of the entire system of capitalist economic relationships with an account of the commodity form. This is the nexus of capitalism as well as the means of understanding contradiction. Where Marx began with the commodity, I would begin to understand the commodity as it is metaphorically reiterated in its packaging.

Of all the attributes of mass-produced commodity packaging today, the most important is the use of plastic. The plastic cover acts as a barrier between the consumer and the product, while at the same time it offers up a naked view of the commodity to the consumer's gaze. Sometimes the plastic covering is moulded to fit the contours of the commodity and acts like a transparent skin between the consumer's hand and the object. Shaped and naked, but veiled and withheld, the display of commodities is sexualized. Plastic packaging defines a game of câche —câche where sexual desire triggers both masculine and feminine fantasies. Strip-tease or veiled phallus— packaging conflates a want for a particular object with a sexualized form of desire.

Packaging prolongs the process of coming into possession of the commodity. A buyer selects a particular item, pays for it, but does not fully possess it until he or she pulls open its plastic case or cardboard box. Possession delivers a commodity's use value into the hands of the consumer. Packaging acts to separate the consumer from the realization of use value and heightens his or her anticipation of having and using a particular commodity. Packaging may stimulate associations with gift-wrapped Christmas and birthday presents. However, plastic commodity packaging reveals what gift-wrapping hides. The anticipation we associate with the gift-wrapped present is for the unknown object. In anticipating a plastic-wrapped commodity, we imagine the experience of its use since its identity is already revealed. In all our experiences of consumption, we are little different from the child who convinces his mother to buy the latest Ghostbuster action figure. From the moment he picks the packaged toy off the shelf, to the moment he passes through the checkout, he will trace the contours of the package with his hands, attempt to scrutinize the toy's detail with his eyes, and lose himself in imagining how it will finally feel to push the lever that makes the Ghostbuster's hair stand on end and eyes pop out with fright at the delightfully cold and gelatinous slime—also included in the package, but not yet available to the touch.

Tania Modleski, in her analysis of soap operas (Modleski, 1982), makes a point about the genre's form that provides a clue to the deciphering of commodity packaging. Modleski identifies “waiting” as the most salient formal feature of soap operas. As we all know, nothing ever really happens nor is any problem ever fully resolved in a soap. The characters who open a particular episode may drop out of sight for a day or two, a character might announce a dramatic or scandalous event, but its culmination and consequences may drag on for weeks. Viewers learn to hold plots and people in suspension, waiting from daily episode to daily episode in unbelieving anticipation of dénouement. As Modleski puts it: “soap operas are important to their viewers in part because they never end…The narrative, by placing ever more complex obstacles between desire and fulfillment, makes anticipation an end in itself” (Modleski, 1982:88). Modleski astutely compares waiting as a formal feature of soap operas with the lived experience of the housewife. Alone at home, her husband at work, some or all of her children at school, the housewife performs all the daily chores necessary to maintain house and family in an all-encompassing ambience of waiting:

Soap operas invest exquisite pleasure in the central condition of a woman's life: waiting—whether for her phone to ring, for the baby to take its nap, or for the family to be reunited shortly after the day's final soap opera has left its family still struggling against dissolution.

(Modleski, 1982:88)

Modleski concludes that the appeal of soap operas resides in the way they make waiting enjoyable. The soap opera turns waiting into an aesthetic. This, then, lifts the housewife viewer out of her real and frustrating experience of waiting, and allows her to apprehend waiting as pleasure.

I would extend Modleski's observations to the way we as consumers relate to the use value of commodities. Mass commodity packaging makes the anticipation of use value into an aesthetic in the same way that the soap opera transforms waiting from an experience into a form. Moreover, commodity packaging defines the anticipation of use value as the commodity's most gratifying characteristic. No commodity ever lives up to its buyer's expectations or desires. This is because in commodity capitalism, use value cannot be fully realized, but rather haunts its fetishized manifestations in the objects we consume. This is true regardless of our economic level of consumption. The shoddy purchase that does not fulfill its advertised promise promotes the pleasurable anticipation of the next (hopefully less shoddy) purchase. Similarly, the high-class piece of merchandise, for instance the sumptuous and expensive new fashion, that in itself seems to live up to all our expectations, also activates anticipation for the next purchase when we take our designer fashion home and hang it next to our now worn and boring collection of clothes. In defining the anticipation of use value as the site of pleasure in the commodity form, capitalism puts the consumer (whether woman, man, child, or adult) in a position analogous to Modleski's housewife. Waiting can only be rendered aesthetically pleasing to someone who is socially isolated and powerless. The housewife who comes to appreciate waiting as pleasure hardly has access to another, more active and affirming mode of getting through the day. Similarly, the consumer learns to associate pleasure with the anticipation of use value simply because commodity culture does not offer use value itself as appreciable or accessible.

Commodity capitalism fully develops the anticipation of use value while use value itself seems to serve no other purpose but to create the basis for its anticipation. Such a separation between anticipation and use value underlies Wolfgang Haug's Critique of Commodity Aesthetics. Haug focuses on advertising in order to develop a definition of commodity fetishism in the context of late capitalism. He draws on Marx's definition of commodity fetishism, but translates the Marxian contradiction between exchange value and use value into the terms of the market economy where the primary contradiction is between buyer and seller. Where Marx saw the commodity form as the embodiment of human labor in the abstract and this as the basis for its creation of exchange value, Haug sees the commodity's use value pressed into the service of sales. The buyer “values the commodity as a means for survival,” whereas the seller “sees such necessities as a means for valorization” (Haug, 1986:15). Haug concludes that commodities have a “double reality.” First, they have a use value; “second, and more importantly, the appearance of use value” (Haug, 1986:16). For Haug, the appearance of use value is essentially “detached” (Haug, 1986:17) from the object itself. This is the aspect of the commodity form that advertising seizes upon and renders sensually perceptible in its words and images. The aspect of the commodity form that Haug defines as appearance would seem to correspond with the category of anticipation. Both suggest that the fetishization of the commodity is for the consumer the fetishization of use. Marx recognized this when he commented: “whenever, by an exchange we equate as values our different products, by that very act, we also equate, as human labour, the different kinds of labour expended upon them. We are not aware of this, nevertheless we do it” (Tucker, 1978:322). The abstraction of labor which is the real basis of the fetish quality of commodities, is not something we as consumers can directly grasp, rather it enters our daily life experience as the inability to apprehend fully or even imagine non-fetishized use values.

Haug's account of commodity aesthetics, particularly the way he sees human sensuality wholly inscribed in the appearance of use value, where it is abstracted and turned into market value, bears a strong resemblance to the way in which earlier Marxist intellectuals developed the notion of reification. The landmark text on reification is included in Georg Lukács’ History and Class Consciousness. Lukács begins with Marx's notion that “in the commodity the social character of men's labour appears to them as an objective character stamped upon the product of that labour” (Lukács, 1971:86), and develops the point that commodity fetishism is both an objective and a subjective phenomenon (Lukács, 1971:87). Objectively, there is a world of commodities and a market economy, whose laws we might apprehend, but which nevertheless seems to obey “invisible forces that generate their own power” (Lukács, 1971: 87). Subjectively, people in commodity capitalism experience the estrangement of their activities as these, too, become commodities. Crucial to Lukács’ definition of reification is the notion that once labor power comes into being as the abstraction of human activity, it extends its influence to human qualities and personality as well. Such objectification, coupled with the highly fragmented and rationalized process of capitalist production, produces “the atomization of the individual”

(Lukács, 1971:91) in consciousness as well as labor. Reification defines the translation of commodity fetishism into human experiential terms.

The transformation of the commodity relation into a thing of “ghostly objectivity” cannot therefore content itself with the reduction of all objects for the gratification of human needs to commodities. It stamps its imprint upon the whole consciousness of man; his qualities and abilities are no longer an organic part of his personality, they are things which he can “own” or “dispose of” like the various objects of the external world. And there is no natural form in which human relations can be cast, no way in which man can bring his physical and psychic “qualities” into play without their being subjected increasingly to this reifying process.

(Lukács, 1971:100)

Common to both Lukács’ and Haug's analyses of the commodity form is the notion that under capitalism human qualities and the sensual dimension of experience are objectified and abstracted—or “detached”—from people and their activities so that they become commodities in their own right, “reified” or “aestheticized.” The problem is, then, how to reverse—or break through—the process so as to recover and affirm all the human qualities that the commodity form negates by abstraction. The most challenging thinking along these lines is Theodor Adorno's Negative Dialectics. Like Lukács, Adorno sees consciousness —our mode of conceptualizing self and world— inexorably shaped by capitalism. Adorno too draws directly on Marx's theory of the commodity, particularly the phenomenon of equivalence. In order for exchange to take place, commodities, which would otherwise be distinct because of their vastly different properties, must achieve equivalence. As previously remarked, it is the abstraction of labor into labor power that produces equivalence. As Marx put it, “the equalization of the most different kinds of labour can be the result only of an abstraction from their inequalities, or of reducing them to their common denominator, viz. the expenditure of human labour-power as human labour in the abstract” (Tucker, 1978:322). Where Marx uses the term “equivalence,” Adorno, whose argument is more properly philosophical, develops the notion of “identity” (Adorno, 1973: 146). The whole of Negative Dialectics is aimed at “breaking through the appearance of total identity,” in order to smash the “coercion” (Adorno, 1973: 146) of identification as a form that has its roots in economics and dominates all human endeavor and thought.

The [exchange] principle, the reduction of human labour to the abstract universal concept of average working hours, is fundamentally akin to the principle of identification. [Economic exchange] is the social model of the principle, and without the principle there would be no [exchange]; it is through [exchange] that nonidentical individuals and performances become commensurable and identical. The spread of the principle imposes on the whole world an obligation to become identical, to become total.

(Adorno, 1973:146)

Adorno sees the possibility of negative dialectics in the fact that capitalism as a system and as a form of consciousness is both total and not total. The abstraction of human labor that permits equivalence both denies and requires the existence of multiple and qualitatively different labors. This is capitalism's contradiction. According to Adorno, contradiction “indicates the untruth of identity” (Adorno, 1973:5)—not because it affirms some wholly other position outside of capitalism, but because it is “nonidentity under the aspect of identity” (Adorno, 1973:5). Negative Dialectics holds tremendous possibilities for rethinking and reclaiming daily-life social practice under capitalism, because unlike the concept of reification, it apprehends fetishism as a tension between the abstracting forces of domination and their utopian antitheses. But how are we to apprehend contradiction? Adorno equates the possibility of contradiction in capitalism as an economic system with the possibility of realizing contradiction in thought. As he sees it, the translation of things into their conceptions leaves something out: a “remainder” which functions as the concept's contradiction. The project of translating negative dialectics into daily life would, then, require ferreting out all the remainders—the resistant, and perhaps quirky, material of practice and relationships that cannot be assimilated in the process of coming to equivalence. Negative Dialectics is written as an unrelenting expoœe—of the overwhelming tendency toward identity and its manifestations in philosophical thought. In the more mundane world of daily life, negative dialectics opposes the homogenization of mass culture, where standardization is marketed as a sign of quality, and the great range of qualitatively different social and cultural forms is transformed into the design details of commodities. What is most interesting about Adorno's writing is that while the notion of identity and all its ramifications are wholly revealed, the category of “non-identity” is never fully described, or analyzed. Adorno implies that to do so would diss...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- A PRIMER FOR DAILY LIFE

- STUDIES IN CULTURE AND COMMUNICATION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- AUTHOR'S NOTE

- 1: UNWRAPPING USE VALUE

- 2: GENDER AS COMMODITY

- 3: LEARNING FROM THE BANANA

- 4: WORK(ING) OUT

- 5: PLAYING HOUSE

- 6: I WANT THE BLACK ONE Is there a place for Afro-American culture in commodity culture?

- 7: SWEET DREAMS Profits and payoffs in commodity capitalism

- 8: EARTHQUAKE KITS The politics of the trivial

- AFTERWORD

- REFERENCES

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Primer For Daily Life by Susan Willis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Popular Culture in Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.