Chapter 1

The Jacked-Up World of Healthcare Financing

Every industry has its quirks. Healthcare may be among the quirkiest. And perhaps the most complicated. Far from being a fairly cohesive industry like retail sales or manufacturing, the healthcare world is made up of overlapping types of service providers, occasionally coordinated but usually not. The two most influential groups are physicians and hospitals.

Physicians

Physicians provide the backbone of medical care and are the primary drivers of the diagnostic and caregiving decisions and processes. Although healthcare information and/or interventions for less serious conditions are available through public health centers, pharmacies, nurse helplines, and other places, physicians determine the treatment path for the most serious medical issues. They're the only ones who can admit a patient to the hospital and approve their discharge, they determine the care decisions during an inpatient stay, and they set the course for post-discharge care. Nothing happens unless a physician writes an order.

About one-third of the nearly 625,000 US physicians who spend the majority of their time in direct patient care are primary care doctors: family physicians, general practitioners, internists, pediatricians, obstetricians/gynecologists, and geriatricians. The rest are specialists and sub-specialists. Primary care physicians generate 51.8% of all office visits.1 The fact that this one-third of the physicians is responsible for half the visits makes sense. Many office visits are for relatively less severe conditions and are appropriately treated by primary care doctors.

Historically, most physicians worked either alone or in relatively small group practices. Over the last few decades, though, more and more individual doctors and groups have joined together to form larger entities, or they have been acquired by hospitals. The days of the small-town family doctor in solo practice are quickly fading.

Hospitals

Hospitals are the other major factor in the healthcare ecosystem. According to the American Hospital Association, there were 6,210 hospitals in the United States in 2017.2 Hospitals are either not-for-profit, governmental entities, or investor-owned. Most are general “community” hospitals while others are considered Academic Medical Centers (AMCs), which combine patient care services, medical education, and academic research. Other hospitals focus on care for selected groups like children or for specific clinical areas like cancer care, behavioral health, or rehabilitation services. In the late 1990s, the federal government established a new category of small, rural hospitals designated as Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs), which are limited-service institutions with 25 or fewer beds. Because of the vital roles they play in their communities, they benefit from slightly enhanced payment terms to help keep them solvent.

People unfamiliar with the inner workings of a hospital can underestimate their complexity. None other than management expert Peter Drucker has called hospitals “the most complex human organization ever devised.”3

Perhaps hospitals' most significant oddity is the fact that historically the people who run the enterprise rarely control what happens within the organization. Typically, a company's top executive has great authority to control the transactions that affect its core business. Although hospital leaders can set policies that influence doctors' decisions in a general way, the final determination about each individual patient rests solely with the physicians. They decide who will be admitted. They decide what tests and procedures will be done. They decide when a patient can be discharged. Every one of these choices carries operational and financial implications for the hospital, and they are made by people who are not always employed by the organization.

Some analysts have likened a hospital to an airport. Airports exist because planes need a place from which to operate and because passengers need a place to connect with the airlines. Each airline is an independent organization that contracts with the airport for various services. Although the airport sets certain broad policies, it doesn't control the airlines' specific internal operations or activities. Each airline company sets its own human resources rules, work requirements, investment strategies, etc. All this is very parallel to the traditional relationship between hospitals and physicians. The hospital “sets the table,” but the physician provides the meal.

However, this semi-independent relationship is beginning to change. In recent years, insurance companies – including the governmental Medicare and Medicaid programs – have encouraged greater coordination among hospitals, physicians, rehab facilities, and other providers. Rather than paying each provider separately and for each individual service they deliver to a patient, they are moving toward a more coordinated single payment where the provider organizations assume increasing financial risk. These new financial incentives foster more resource alignment.

One way this happens is through a single bundled payment to an entity such as an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) that assumes clinical and financial responsibility for a patient's episode of care. The ACO either owns the necessary resources or contracts with others to access them. A related concept is value-based payment where patients are encouraged to use services that can demonstrate superior and cost-efficient care. The best way to achieve these goals is through greater coordination among all the organizations providing care. And many hospitals have concluded that the best way to manage care is through owning the “assets,” in this case physician practices. As a result, many hospitals have purchased practices or have developed stronger contractual relationships with them.

Although this movement toward bundled payments or value-based care has been growing, the vast majority of healthcare is still paid on a piecemeal, fee-for-service basis where every time a physician or hospital provides a service, they get paid for that specific intervention. Typically, procedural-based activities (i.e., “doing something” for a patient like replacing a hip) are more lucrative that the medically based ones (such as hospitalizing a patient while they recover from pneumonia). A 2018 survey of health system executives reveals that 78% of care is still covered under a fee-for-service arrangement. However, the remaining 22% that is paid under some kind of value-based care arrangement is growing and is expected to rise to 25% in 2019.4

The Three-Legged Stool

One of the keys to understanding the operating dynamics within the healthcare industry is recognizing that it is like a three-legged stool where all three legs are equally important and must be kept in balance. The three legs of the healthcare delivery stool are access (both geographic and financial), quality, and cost. It's easy to get two of these right but very tough to keep all three in perfect balance.

A given region may generally offer high-quality, affordable care for most things but may have an undersupply of certain medical specialists or other services. This can be especially problematic in rural or impoverished areas.

Affordable care may be within a patient's reach, but if it's of poor quality, people will avoid it unless they have no other choice.

Patients may have physical access to great quality care but if they can't afford it – either because they don't have insurance coverage or because they can't pay for it out of their own pockets – it does them no good. Also, a healthcare industry whose costs continue to spiral out of control is unsustainable in the long run.

So, this is the challenge to the healthcare field: figuring out a way to keep these three needs in equilibrium.

Now let's take a more detailed look at the inner workings of healthcare financing.

How Healthcare Is Paid For

Because of the extensive debate leading up to passage of the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA – also known as Obamacare), most Americans realize that we are about the only major “first world” nation that does not provide universal healthcare coverage for our citizens. Many countries offer a single-payer system where the government operates a publicly funded insurance plan. In some cases they also own the hospitals and employee all personnel.

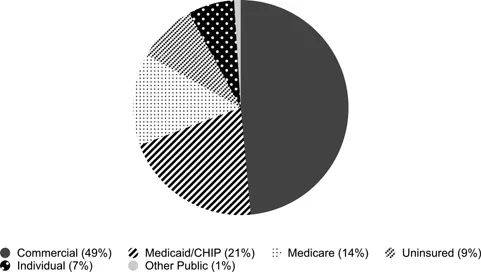

By contrast, the United States has a patchwork of public and private insurance programs. Figure 1.1 shows the percentage of the US population covered under various insurance arrangements as reported by the Kaiser Family Foundation.5

Figure 1.1Health Insurance Coverage of the US Total Population – 2017.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Forty-nine percent of the population is enrolled in private commercial insurance programs. The public programs cover 36% of the total, broken down as follows:

Medicaid (the program for low-income individuals)/Children's Health Insurance Program (the program for low-income children) – collectively 21%

Medicare (the program for the elderly) – 14%

Other public programs – 1%

Let's look at how well the major public programs (Medicaid and Medicare) cover the cost of care for their enrollees. Before we do so, however, I would like to comment on the different ways healthcare population, utilization, and economic statistics are presented. Readers are often confused when they see various statistics, studies, articles, or news stories that show conflicting numbers.

First of all, each type of insurance program...